The importance to a football club’s bottom line of

qualifying for Europe has been evident for many years, as the money distributed

to teams competing in UEFA’s competitions can have a significant impact on their

revenue.

This is even more the case with the latest cycle of UEFA’s

TV deals that has seen the total funds available for distribution to clubs rise

by 38% in 2015/16 from €1.270 billion to an amazing €1.756 billion. The lion’s

share of €1.345 billion went to the Champions League, but the Europa League also

received a much larger proportion than the previous arrangement, amounting to €411

million.

Despite the steep growth in the Premier League’s TV deals,

Europe is still important for English clubs, as seen by Manchester City earning

more than any other club with €84 million, followed by Real Madrid €80 million,

Juventus €76 million, Paris Saint-Germain €71 million, Atletico Madrid €70

million and Chelsea €69 million.

In other words, City received more money for reaching the

Champions League semi-finals than Real Madrid did for actually winning the

trophy. This puzzling anomaly is down to the high value of the British TV deal,

which means that English clubs can earn more than teams from other countries

who progress further in the tournament.

This was also demonstrated in the Europa League, where the

top earners were Liverpool €38 million and Tottenham Hotspur €21 million, followed

by Villarreal €16 million, Lazio €15 million, Fenerbahce €15 million and

Borussia Dortmund €14 million.

The amount earned by Liverpool for reaching the final showed

that clubs can now generate useful cash from the Europa League. The Reds’ distribution of €38

million was the 14th highest overall in Europe last season, i.e. more than the money earned by 19

clubs that qualified for the Champions League group stage.

The discrepancy between different countries’ receipts is

highlighted by comparing the top two earners. Manchester City’s €84 million

total was geared towards the TV pool €47 million (56%) with prize money €37

million (44%), while it was the opposite for Real Madrid, who earned more from prize

money €54 million (67%) compared to the TV pool €26 million (33%).

The contrast is just as stark for the Europa League, e.g. Villarreal

received €16 million for reaching the semi-final, split between prize money €8

million (49%) and TV pool €8 million (51%); while Tottenham received €21

million, i.e. €5 million more, for only reaching the last 16, split between

prize money €6 million (28%) and TV pool €15 million (72%).

This is linked to the huge British TV deal with BT Sports,

who paid a hefty €299 million a season for the 2015-18 three-year cycle. This

is more than double the €132 million paid by the combination of Sky Sports and

ITV for the previous agreement.

As a result of the higher deal, English clubs did much

better (at least from a financial perspective) in 2015/16 with Manchester City

leading the way, as their revenue increased by €38 million (84%) from €46

million to €84 million. Similarly, Chelsea’s revenue rose by €30 million (76%)

from €39 million to €69 million, while Arsenal’s revenue grew by €17 million

(47%) from €36 million to €53 million.

Liverpool’s revenue was also 11% higher, even though they

competed in the Europa League, as opposed to the more lucrative Champions

League the previous season. Tottenham’s revenue was an astonishing 244% (€15

million) higher for going one round further in the Europa League.

Last Five Years

To emphasise the value of the Champions League to the

leading clubs, it is worth exploring how much they have earned in the last five

years. At the top of the pile are Juventus with €281 million, which is perhaps

somewhat surprising, given that they have only reached the final once in that

period, but is again testament to the might of the TV pool.

Next come Real Madrid €277 million (winners in 2014 and

2016), Bayern Munich €256 million (winners in 2013), Chelsea €253 million

(winners in 2012) and Barcelona €246 million (winners in 2015). All to be

expected.

However, this table also highlights a core element of the

strategy of the nouveaux riches

clubs, i.e. spending for success, as we find Paris Saint-Germain and Manchester

City in sixth and seventh places with €228 million and €222 million

respectively.

In England consistency has been rewarded with the three

clubs ever present in the Champions League leading the way: Chelsea €253

million, City €222 million and Arsenal €177 million. Manchester United would

have been higher if they had qualified for Europe in 2014/15, but they still

earned €159 million.

Despite qualifying for the Champions League in 2014/15 and

reaching the Europa League final in 2015/16, Liverpool are a long way back with

€77 million, while Tottenham’s Europa League residency has earned them only €41

million.

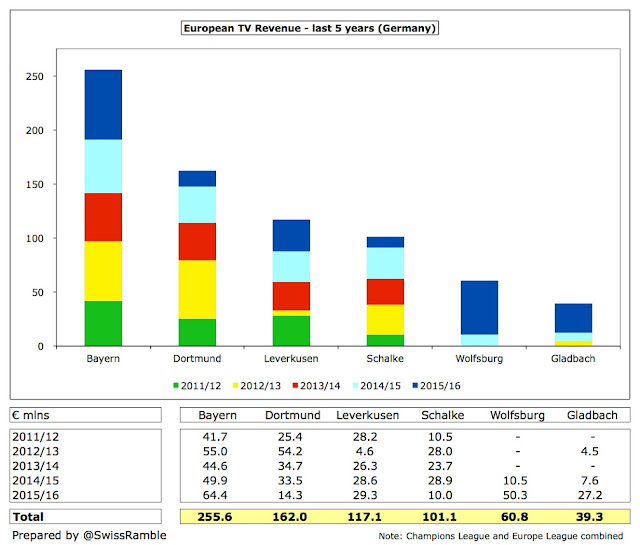

In Germany Bayern’s Champions League exploits have earned

them €256 million, almost €100 million more than Borussia Dortmund’s €162

million. Europe has allowed the Bavarian giants to put even more distance

between them and their domestic rivals.

All of these have earned much less: Bayer Leverkusen €117

million, Schalke 04 €101 million, Wolfsburg €61 million and Borussia

Mönchengladbach €39 million (the latter two almost all from 2015/16).

The gap between the top club and the others is even wider in

Italy, as Juventus’ €281 million is around €150 million more than the next club

Milan, whose €129 million was restricted by not qualifying for Europe in the

last two seasons. Juve’s performance is even more impressive, given that they

did not even qualify for Europe in 2011/12.

Milan’s place in the Champions League has been taken by

Roma, who have earned €116 million in that period. The next highest are Napoli

€100 million and Lazio €51 million. Inter’s recent difficulties are highlighted

by the nerazzurri only earning €45

million from Europe in the last five

years. This is less than the €49 million they earned in 2010/11 when they

defeated Bayern Munich to win the Champions League.

Spain is all about the big two with Real Madrid €277 million

and Barcelona €246 million a long way ahead of Atletico Madrid €179 million,

who are in turn much higher than Valencia €89 million, Sevilla €69 million and

Athletic Bilbao €51 million.

Sevilla are an interesting case, as their reward for winning

the Europa League three times in a row is clearly much less than qualifying for

the Champions League. Following a change in the rules, Sevilla’s victory in

2014/15 gave them a place in the following season’s Champions League, so their

2015/16 €35 million revenue is split between €21 million from that competition

and €14 million from dropping down to the Europa League.

France demonstrates Paris Saint-Germain’s domination, as

their €228 million is €150 million more than Lyon’s €78 million, closely

followed by Marseille €73 million and Monaco €69 million.

Paris Saint-Germain’s competition has been weakened by the

other French Champions League spots being shared among their domestic rivals,

e.g. Lille and Montpellier have also featured in this period. In fact, PSG only

earned €2 million in 2011/12, so their earnings in the last four seasons have

been really high.

Portugal demonstrates the rivalry between Benfica €111

million and Porto €98 million, while the others are nowhere: Sporting €31

million, Braga €22 million, Estoril €5 million and Belenenses €4 million.

Galatasaray’s “welcome to hell” has been worth €98 million,

even though there was no revenue in 2011/12, a long way ahead of Trabzonspor

€37 million, Besiktas €27 million and Fenerbahce €26 million.

UEFA Distribution Model

As we have seen, the amount of revenue available to

distribute to the clubs increased significantly in 2015/16 by €487 million

(38%) from €1.270 billion to €1.756 billion, but this masked a couple of

interesting developments.

First, UEFA decided to give proportionally more to the

Europa League, whose pot rose by 71% (€171 million) from €240 million to €411

million, while the Champions League fund “only” rose by 31% (€315 million) from

€1.030 billion to €1.345 billion. The Europa League has always provided a

platform for smaller clubs to compete in Europe, but now has the added bonus of

being financially worthwhile (though obviously still no match for the Champions

League money).

In UEFA’s terms, clubs in the Europa League now receive

about €1 every €3.3 received by clubs in the Champions League, compared to €4.3

under the old arrangement. This might be considered a step in the right direction,

but, put another way (and rather less impressively), the Europa League still

only has 23% of the total pot, albeit up from 19% the previous season.

"At The Height Of The Fighting"

Second, UEFA has endeavoured to reward success more by

increasing the amount allocated to prize money compared to the TV pool. In

2014/15 the split was 52% for prize money and 48% for TV pool, but the 2016/17

budget is essentially a 60:40 split in favour of prize money.

UEFA’s 2016/17 estimate provides a useful break-down of how

the distribution model works. Based on gross commercial revenue of €2.350

billion, 12% (€282 million) is required to cover organisational and

administrative competition-related costs, while solidarity payments have been

significantly increased to €200 million, comprising €82 million for those clubs

participating in the qualifying rounds and €118 million to national

associations for club development projects.

After these deductions, we are left with €1.868 billion of net commercial revenue. Of

this, €149 million (8%) is reserved for “European football”, i.e. remains with

UEFA, which gives a €1.719 billion pot for distribution to the clubs. This is

equivalent to the €1.756 billion in the 2015/16 season, which was higher than

expected due to more commercial revenue proceeds than budgeted.

Champions League

Looking at the payments by country for the Champions League,

it’s a case of the rich getting richer, as the payments are dominated by the

Big Five leagues (Spain, England, Germany, Italy and France). They accounted

for 71% (€949 million) of the total €1.345 billion pot.

Spain earned the most with €254 million, closely followed by

England €245 million, though Spain’s money was largely due to success on the

pitch with €105 million from prize money, nearly twice as much as England’s €54

million. In contrast, England’s share of the TV pool of €143 million was

considerably higher than Spain’s €89 million.

Italy were also boosted by a relatively high TV pool of €112

million, while their prize money was just €23 million. Germany’s €52 million

prize money was almost the same as England, but their TV pool was less

than half at €68 million.

Champions League – Prize Money

In 2015/16 each of the 32 teams that qualified for the

Champions League group stages was guaranteed a minimum participation fee of €12

million - even if it lost every single game. This was a significant 40% increase

on the 2014/15 fee of €8.6 million.

In addition, the performance bonuses in the group stage were

increased by 50% to €1.5 million for each win, though stayed at €500,000 for a draw. So if a team were to

really put the pedal to the metal and won all six of its group

matches, it would get €9 million on top of the participation fee.

If a team qualifies for the last 16, it is awarded €5.5

million, while there is additional prize money for each further stage reached:

quarter-final €6 million, semi-final €7 million, final €10.5 million and winners

€15 million.

Therefore, the maximum that a club could have earned (by

winning all its group matches and lifting the trophy) was an impressive €54.5

million (not counting the TV pool), up from €37.4 million in 2014/15. The prize

money for 2016/17 has been tweaked upwards again, so the maximum will rise to

€57.2 million this season.

Clubs involved in the play-offs shared a total of €50

million: €2 million for each winner and €3 million for each club that was

eliminated. Teams defeated in the qualifying rounds received: first qualifying

round €200,000; second qualifying round €300,000; third qualifying round

€400,000. In addition, each domestic champion that did not qualify for the

group stage received another €250,000.

As we have seen, Spain earned much more money from prize

money in the Champions League than any other country with their €165 million,

far ahead of England €102 million and Germany €100 million. This is a fair

reward for the two Madrid clubs reaching the final, meaning that the winners

Real Madrid trousered €54 million with their city rivals Atleti earning €48

million, while Barcelona got €31 million for reaching the quarter-finals.

The two other semi-finalists, Bayern Munich €39 million and

Manchester City €37 million, helped boost Germany and England. France and Italy

were a long way back earning just €48 million and €47 million respectively,

partly due to their third clubs not reaching the group stages.

Champions League – TV Pool

In addition to prize money, clubs received a share of the

television money from the TV (market) pool, which amounted to €578 million for

the Champions League in 2015/16. Each country’s share of the market pool is

based on the value of the national TV deal, which means that English clubs have prospered

from the huge BT Sports deal, though it should be noted that around half of

this goes into the central pot, so they do not receive the full benefit.

Half of the TV pool depends on the position that a club

finished in the previous season’s domestic league. For countries with four

clubs, the team finishing first receives 40%, the team finishing second 30%,

third 20% and fourth 10%. If only three clubs reach the group stage, the share

would increase to 45%, 35% and 20% (for national associations ranked 1 to 3,

i.e. Spain, England and Germany).

For countries with only two representatives through to the

group stage, the share is 55% and 45% (for national associations ranked 4 to 6

and 13 to 16). If only one team gets through to the group stage, they would

take 100% of that country’s TV pool.

In other words, from a purely financial perspective a club

would hope that the other clubs from its country would be eliminated in the qualifying

and play-off rounds, as the available money would then be divided between fewer

clubs.

The other half of the TV pool depends on a club’s progress

in the current season’s Champions League, which is calculated based on the number of games

played (starting from the group stages).

Thanks to BT Sports’ exclusive “game changer” of a deal,

England’s TV pool was the highest in Europe at €143 million. Nevertheless, the

club that earned the most from the TV pool in 2015/16 was Juventus, whose €53

million was higher than Manchester City’s €47 million, despite only reaching

the last 16. This is because the Italian TV pool of €112 million was only

shared between three clubs compared to the four in England.

It was even worse for the Spanish clubs, where €89 million

was shared between five clubs after Sevilla were awarded a place in the

Champions League for winning the Europa League in 2014/15. German clubs were

hit by the “double whammy” of having the lowest TV pool of €68 million, allied with

having to share this sum between four clubs.

England’s TV pool increased by a hefty 52% (€49 million)

from €94 million to €143 million in 2015/16. Manchester City earned the most with €47 million, even though they only finished second in the Premier League in

2014/15, due to their achievement in reaching the semi-final when no other

English club got beyond the last 16.

One little known fact is that English clubs receive less

from the TV pool when a Scottish club (usually Celtic) qualifies for the group stage, as they

are awarded 10% (based upon the population split), because there is no separate

Scottish broadcasting deal with UEFA.

If an English club were to enjoy a perfect season, I

estimate that they could earn around €113 million from the Champions League:

the maximum prize money for winning the trophy and all six group games would be

€57 million; while the TV pool could be as high as €56 million. This assumes:

(a) they won the Premier League the previous season; (b) the other English

clubs were all eliminated at the group stage.

Bayern Munich only received €26 million from the TV pool in

2015/16, even though they won the Bundesliga

the previous season and reached the Champions League semi-final, highlighting just how low the German TV deal is. Moreover, last season this only increased by 4% to €68

million.

Spain’s TV pool rose by 6% (€5 million) from €84 million to

€89 million, but the most earned was only €27 million by Barcelona, as this had

to be shared between five clubs including Sevilla from the Europa League.

This demonstrated a new rule, whereby a club that qualifies for the Champions League by winning the Europa League (i.e. like Sevilla) or

indeed the Champions League, but would not have qualified via their position in

the domestic league, does not receive any money from the first half of the TV

pool.

The Italian TV pool grew by an impressive 19% (€18 million) in 2015/16 from €94 million to €112 million. The last two seasons' payouts show how

Juventus and Roma have benefited from the inability of Italy’s third club to

reach the group stages, first Napoli in 2014/15 and then Lazio in 2015/16.

Even though a new rule introduced last season meant that a

club eliminated in the play-offs would be allocated 10% of that country’s TV

pool, the vast majority of the large Italian TV pool was still shared between just two clubs.

It was a similar story in France with Monaco eliminated in

the play-offs in 2015/16, thus receiving 10% of the French TV deal, which

increased by 11% (€7 million) from €68 million to €75 million. Lille received nothing for losing their play-off in 2014/15, as the rules were only changed the following season.

Paris

Saint-Germain have benefited from regularly winning Ligue 1, but the relatively small differential between first and

second place (55% vs. 45%) has resulted in good payouts to Monaco and Lyon in

the last two seasons.

Europa League

The payments by country show a more equitable revenue

distribution in the Europa League. The share received by clubs from the Big

Five leagues was still the highest, but only 52% (€216 million) of the total €411

million, compared to 71% of the Champions League money.

The Europa League features clubs from many more countries

than the Champions League, e.g. in 2015/16 24 countries were represented in the

Europa League (group stages onwards), compared to 16 in the Champions League

group stages.

England led the way with €63 million, ahead of Spain €47

million, though again this was more down to the TV pool (England €44 million

vs. Spain €20 million) with Spain once again doing better on the pitch,

resulting in higher prize money (Spain €22 million vs. England €14 million).

Europa League – Prize Money

The allocation of prize money in the Europa League is much

the same as the Champions League, though the sums involved are clearly smaller

and there are a couple of other differences.

In 2015/16 each of the 48 clubs involved in the group stages

received a participation fee of €2.4 million, up from €1.3 million the previous

season. In addition, there was €360,000 for each win and €120,000 for each draw

in the group stage, up from €200,00 and €100,000 respectively.

One difference in the Europa League, presumably to encourage

clubs to give their all in this secondary tournament, is an additional bonus for teams

that qualify for the knock-out stages, with the group winners earning €500,000

and runners-up €250,000.

"One More Time"

Clubs receive a further €500,000 for reaching

the last 32, €750,000 for the last 16, quarter-finalists €1 million and semi-finalists

€1.5 million. The Europa League winners collected €6.5 million and the finalists

€3.5 million.

Thus, the maximum that a club could receive is €15.31

million, 55% up from the previous season’s €9.9 million. That’s now a pretty

good incentive, compared to the €6.2 million prize money awarded to the 2011/12

winners Atletico Madrid.

One other difference to the Champions League is that only

clubs eliminated in the play-offs receive a payment (of €230,000). Teams

defeated in the qualifying rounds received: first qualifying round €200,000;

second qualifying round €210,000; third qualifying round €220,000.

Europa League – TV Pool

The allocation of the TV pool in the Europa League is again

similar in principle to the Champions League, as half is based on performance

in the previous season’s domestic competitions and half on the progress in this

season’s Europa League, but there are some subtle differences.

The percentage split for the first half again depends on the

number of teams qualified from a country, but if a domestic cup winner reaches

the group stage, then that club receives a higher share for this element. For

example, if four clubs qualified, then the cup winner would receive 40% with

the other three clubs getting 20% apiece; if no cup winner, then each of the

four clubs would receive 25%.

OK, that’s relatively straightforward, but the second half

of the TV pool is more complicated. First, it is divided up between each round

of the Europa League: group stages 40%, last 32 20%, last 16 16%,

quarter-finals 12%, semi-finals 8% and final 4%.

The stage money is then split into as many portions as there

are countries represented by at least one club in the round concerned,

proportional to the value of the relevant country’s TV deal. Each country’s

share is then split equally among all the country’s clubs participating in that

round.

Let’s take the England TV pool in 2015/16 as an example. As the

total TV pool was €183.1 million, €91.6 million was available for participation and €91.6 million for performance.

England contributed around 20% of the TV pool, so their share of the first

(participation) half was 20% of €91.6 million, i.e. €17.9 million. As there was

no cup winner qualified from England, this was split evenly between Liverpool

and Tottenham, resulting in €8.9 million each.

For the second (performance) half, I have estimated

England’s share of the TV pool in each round. The assumptions are pretty solid

in the latter stages of the tournament, e.g. the final is a simple carve-up

between England (62%) and Spain (38%), but the earlier stages require more

guesswork.

In the group stage, England’s share was divided evenly

between Liverpool and Tottenham, while Manchester United were added for the

last 32 and last 16, having dropped down from the Champions League, which meant

one-third for each club.

From the quarter-finals onward, Liverpool were England’s

only remaining representative, so they took 100% of England’s share. This

success resulted in Liverpool earning the substantial sum of €26.4 million from

the TV pool.

"Everybody's Happy Nowadays"

Other Factors

As anybody who has opened a newspaper recently will know, Brexit

has had a dramatic impact on the exchange rate. In particular, the weakening of

the Pound against the Euro has significantly increased the UEFA revenue in

Sterling terms.

To illustrate this impact, Manchester City’s 2015/16

distribution of €84 million would be worth £72 million at the current exchange

rate of 1.17, compared to just £60 million at the mid-2015 rate of 1.44. As the

saying goes, every cloud has a silver lining.

In addition to the TV money from UEFA, clubs playing in Europe also benefit

from additional match day revenue. Not every club analyses this revenue stream

between different tournaments, but as an example of how much this can be worth,

Roma’s €52 million match day revenue in 2015/16 included €29 million from the

Champions League.

Furthermore, participation in the Champions League should

boost a club’s sponsorship revenue, both in the short term through contractual

bonuses, and longer term by strengthening the attractiveness of the brand

through increased exposure and a better profile.

However, there can also be a downside, as shown by

Manchester United’s kit supplier deal with Adidas. This is worth an astonishing

£750 million over the next 10 years, i.e. £75 million a year, but if United

fail to participate in the Champions League for two or more consecutive

seasons, then the payment for that year would reduce up to 30%, i.e. £22.5

million.

"When the Angel sings"

Here’s To Future Days

To place the €1.756 billion from UEFA’s competitions into

perspective, it is still considerably less than the €3.3 billion a season from the

new Premier League TV deal. Incredible as it may seem, this means that the

bottom placed club in the English top flight will earn more than the Champions League winners this season.

Nevertheless, European money still makes a difference for

the elite clubs and there’s little sign of the gravy train slowing down with

UEFA predicting a 30% rise in revenue for the next 2018-21 cycle. That’s

useful, but what is really thought-provoking is that there are plans to change the

distribution model.

First, the big four leagues (England, Spain, Germany and

Italy) will each receive four guaranteed places in the Champions League group

stages, thus taking up half of the available 32 places. This is no big deal for

Spain, England and Germany, as their four representatives invariably qualify

for the group stages. However, Italy are the big winners here, as they

currently only have three places – and also have a disastrous record in the play-offs.

"Love don't Costa thing"

In addition, the distribution of the TV pool will be

amended, so that each country will retain much less from its national TV deal than

the current arrangement (reportedly down from around 50% to 15%) with the vast

majority going into the central plot in future. So far, so good, as a more even distribution

of the richer countries’ TV wealth is probably no bad thing and should help boost

competitive balance.

However, here’s the rub: the future split will be based on

individual clubs’ UEFA co-efficient, which has been modified to include credit

for historical performances. Again, this just happens to favour Italian clubs

like Milan and Inter, who have not even qualified for the Champions League

recently, but can boast several trophies in their glorious past.

It will also prove advantageous to the old establishment,

e.g. Manchester United would do better out of the new approach to co-efficients than

their “noisy neighbours” Manchester City.

"New Gold Dream"

ECA chairman, Karl-Heinz Rummenigge, boasted, “I am pleased

that we have managed to reach quick and simple decisions for the good of

football.” That’s one way of putting it, Kalle.

In fairness to UEFA, they are caught between a rock and a hard

place, as the leading clubs carry the persistent threat of forming a breakaway Super

League, but this proposed change still leaves a sour taste in the mouth.

That man Rummenigge, also Bayern Munich’s chief executive,

had shown his hand back in 2013, when he complained, “The highest prize is the

Champions League, but it is a competition where there are no guarantees, and

the things you take for granted in domestic football don’t always work.”

Hence, the desire of the leading clubs to make Europe’s premier tournament as much of a closed shop as possible. As The Clash once sang, it is indeed a “Safe European Home”, at least for a privileged few.

Hence, the desire of the leading clubs to make Europe’s premier tournament as much of a closed shop as possible. As The Clash once sang, it is indeed a “Safe European Home”, at least for a privileged few.