Hull City started the 2014/15 season with much optimism

after the previous year’s exploits, when they had comfortably retained their

Premier League status and reached the FA Cup final for the first time in their

history, only losing 3-2 to Arsenal after extra time in a thrilling match. It

was therefore particularly disappointing the way things turned out, as their

Europa League adventure ended almost before it had started and, most painfully,

they were relegated on the last day of the season.

Manager Steve Bruce pointed to the lack of goals: “Nearly

50% of the games we’ve played, we’ve not managed to score. That’s given us too

much to do. It’s a pretty damning statistic.” Indeed it is, but in fairness

Hull were badly affected by an appalling run of injuries, as they lost Robert

Snodgrass in the opening league game and Nikica Jelavic and Mohamed Diamé for

long periods.

Nor were they helped by some off-pitch issues with

midfielder Jake Livermore testing positive for cocaine and the temperamental

Hatem Ben Arfa unexpectedly doing a runner in December.

Steve Bruce has admitted that relegation took him by

surprise: “When the transfer window closed at the end of August, I looked at

our squad and was quite happy.” Little wonder, as owner Assem Allam had

sanctioned a huge outlay on the transfer budget.

In the summer, Hull purchased Abel Hernandez, Snodgrass,

Diamé, Livermore, Michael Dawson, Andy Robertson and Harry Maguire, while

also recruiting Ben Arfa and

Gaston Ramirez on loan. They later brought the total spend to more than £40

million when they also bought Dame N’Doye in the January transfer window.

This continued the trend of big spending following promotion

in 2013. In fact, Hull have splashed a hefty £66 million in the last two

seasons with a net spend of a cool £50 million. That works out to an average

gross spend of £33 million in the last two seasons, which is a massive increase

over the £5 million average in the previous seven seasons. Over the same

periods, Hull’s average spend on a net basis has shot up from £3 million to £25

million.

It may be a surprise to some, but Hull’s total net spend of

£50 million for the last two seasons was actually the 8th highest in the

Premier League. They were obviously still behind the usual suspects (Manchester

United, Manchester City, Arsenal, Chelsea and Liverpool), but around the same

level as Crystal Palace and West Ham who both outperformed the Tigers.

Given the substantial investment in the team, Hull really

should not have struggled so badly last season. The experienced Michael Dawson

summed it up best: “The players that the owners and manager have brought in –

they spent a lot of money – and we haven’t performed. We should have done

better and should be in the Premier League.”

Maybe they were distracted by all the shenanigans over

Allam’s campaign to rebrand the club as Hull Tigers, which has caused

widespread anger among City fans. The owner’s belief is that a name change

would mean that Hull would be better known globally, allowing the club to

better tap into Far Eastern markets. Commercial revenue growth is an

understandable objective, but it is by no means guaranteed that simply changing

the name would result in additional riches. In any case, the Football

Association has recently rejected Allam’s application to change the name for a

second time.

"There ain't nothing like a Dame"

Furthermore, the way that the owner has justified the change

has been a PR disaster, describing the Hull City name as “irrelevant, common

and a lousy identity”. Fans that opposed his “textbook marketing” idea of

shortening the name were labeled “hooligans and a militant minority”. As if

that weren’t enough, he then suggested that those fans "can die as soon as

they want, as long as they leave the club for the majority who just want to watch

good football.”

That’s a wonderful way to alienate the fan base, which is a

great shame, as the owner, who has lived in Hull for over 40 years since

arriving from Egypt, has done a lot of good things for Hull City since

acquiring the club in December 2010.

The previous regime had brought the club to the brink of

insolvency with the auditors stating that there was “significant doubt over the

company’s ability to continue as a going concern.” Allam effectively saved the

club by staving off a winding-up petition and repaying the debts that Hull had

built up under property investor Russell Bartlett. He has since been true to

his word to invest in the club by providing substantial funding of around £70

million and bringing a degree of financial stability.

This is reflected in the 2013/14 accounts, the most recent

figures published, which show that Hull converted a £25.6 million loss the

previous season to a £9.4 million profit, representing a £35 million

improvement following promotion to the Premier League.

Revenue grew by £67.5 million (around 400%) from £17.0

million to £84.5 million, largely thanks to the much higher television deal in

the top flight, which contributed £60 million of the increase. Match day was

also up £6.1 million, including £3.9 million from the FA Cup run, while

commercial income was £1.4 million higher. However, the higher costs of

competing in the Premier League saw wages rise by £17.4 million (67%) to £43.3

million, while player amortisation was £7.6 million higher.

There was also a £6.3 million provision made against amounts

due from the group company Superstadium Management Company Limited (SMC), which

operates the stadium and holds the leasehold of the stadium, as granted by the

local council.

"I see you, baby, Robert Snodgrass"

As a technical aside, Hull City also show parachute payments

under Exceptional Items, but I have included these in revenue to be consistent

with other football clubs.

It should also be noted that Hull shortened their reporting

period to 11 months by moving the accounting close to 30 June to be in line

with the football season. This meant that the 2013/14 figures excluded July’s

costs of £6.1 million, so the profit would have been reduced to £3.3. million

for the full 12 months.

In addition, the club’s sister company, SMC, reported losses

of £5 million, including write-offs to the stadium mortgage inherited from the

previous ownership. As Ehab Allam, Assem’s son and fellow director, said, “It’s

obviously very disappointing to be almost four years into the ownership and

still paying off the debts of the previous regime. We would have wanted to

reinvest those sums back into the squad.”

Therefore, the combined loss for Hull City Tigers Limited

and SMC would be £1.7 million, but this still represents huge progress

considering the 2012/13 accounts showed a loss of nearly £26 million.

That said, most Premier League clubs posted profits in

2013/14, thanks to the increase in TV money allied with the financial fair play

regulations that restricted wages growth, so Hull’s £9 million surplus is not

really that special an achievement. In fact, only five of the 20 clubs reported

losses, a major improvement on previous seasons.

It is also true that clubs promoted to the Premier League

always receive a significant boost to their finances. In this way, the other

teams promoted with Hull, namely Crystal Palace and Cardiff City, also improved

their bottom line by £21 million and £18 million respectively. Cardiff still

made a loss in the top flight, but that was largely due to their decision to

book £12 million of impairment charges.

After buying the club, the Allams predicted “future trading

profitability”, but they had to absorb £55 million of losses before reaching

the Premier League: £20 million in 2010/11, £9 million in 2011/12 and £26

million in 2012/13. In fairness, most clubs lose money in the Championship and

Hull were no exception.

The chunky loss in 2012/13 was part of deliberate strategy:

“The directors made the ambitious decision to go for promotion and to this end

invested heavily in the club.” This objective was achieved, which actually

increased the loss, as it resulted in bonuses being paid out to the players,

management and staff.

Even though Hull’s accounts back in 2008 described

profit/loss resulting from player sales as “a significant figure in our

accounts”, that is not really the case with a meagre profit of just £1.2

million being made in the last nine years, partly due to the £8.3 million loss

reported in 2011.

While Hull only made £1.7 million from player sales in

2013/14, other clubs generated sizeable profits from this activity: Tottenham

£104 million (largely Gareth Bale to Real Madrid), Chelsea £65 million (David

Luiz to PSG), Southampton £32 million (Adam Lallana to Liverpool) and Everton

£28 million (Marouane Fellaini to Manchester United).

Hull’s profit from player sales will be boosted in 2014/15

by the sales of Shane Long to Southampton and George Boyd to Burnley, though

many out-of-contract players have simply been released for no fee.

The recent big spending in the transfer market has been

reflected in Hull’s P&L account via player amortisation, which surged from

£2 million to £10 million in 2013/14, much in the same way that it increased

the last time Hull were in the top flight.

However, this is still one of the smallest in the Premier

League, only ahead of Crystal Palace £6 million and WBA £5 million, though it

will surely rise again in the 2014/15 accounts. As a rule, low amortisation is

normally the result of low spending on player recruitment, while those clubs

that are regarded as big spenders logically have the highest amortisation

charges, e.g. Manchester City £76 million, Chelsea £72 million and Manchester

United £55 million.

To clarify this point, transfer fees are not fully expensed

in the year a player is purchased, with the cost being written-off evenly over

the length of the player’s contract – even if the entire fee is paid upfront.

As an example, Robert Snodgrass was reportedly bought for £6 million on a

three-year deal, so the annual amortisation in the accounts for him is £2

million.

As a result of these accounting complications, clubs often

look at EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest, Depreciation and Amortisation) for a

better idea of underlying profitability. Hull themselves have described EBITDA

as “a relevant measure, as it is a closer approximation to cash generation than

straightforward profit and loss.” On that basis, Hull’s EBITDA has invariably

been negative, though it improved considerably in 2013/14 from minus £21

million to £27 million.

That’s not too bad at all, leaving them sandwiched between

Newcastle United £27 million and Everton £25 million. Most Premier League clubs

are in a fairly narrow range of £20-30 million EBITDA, though the big boys are

in a class of their own: Manchester United (an incredible) £130 million,

Manchester City £75 million, Arsenal £632 million, Liverpool £53 million and

Chelsea £51 million.

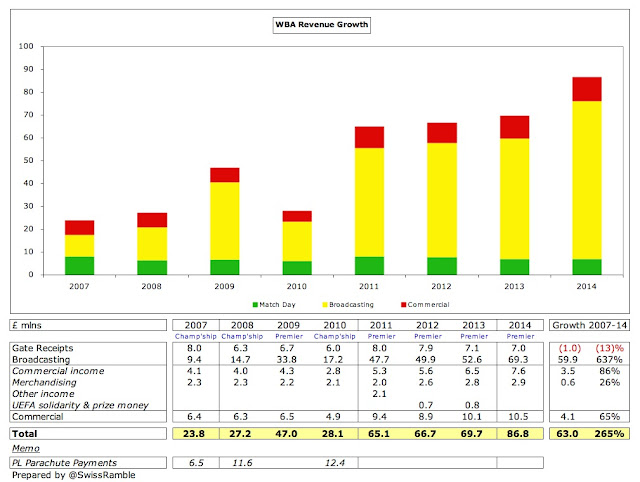

Hull’s revenue is largely a story of whether they are

playing in the Championship or the Premier League with promotions in 2009 and 2014

increasing revenue by £40 million and £67 million respectively. The larger

increase in 2014 is due to the higher centrally negotiated Premier League TV

deal.

Hull’s revenue reduced each year in the Championship

following relegation in 2011 from £27 million to £24 million then £17 million,

purely because the parachute payments from the Premier League fell from £16

million to £13 million then £6 million.

After the 2013/14 accounts were published, Ehab Allam spoke

about his plans to expand Hull’s income, “We’re not where we want to be, but

we’re heading in the right direction.” Not any more, as relegation will take a

large bite out of these numbers.

Despite the sharp revenue growth in 2013/14, Hull’s £84

million was actually the second lowest in the Premier League, only ahead of

Cardiff City £83 million. As Ehab Allam said, “The key is where our income is

compared to our competitors. We can’t be complacent, because, as we stand, a

lot of our rivals have an advantage over us. This club needs a long-term sustainability

and we can’t do that by having the income of a side in the bottom three.”

Like every other Premier League club, Hull were in the top

40 revenue earners worldwide, according to the Deloitte Money League, which

sounds very impressive, if it were not for the fact that this does not help at

all domestically. For example, five English clubs earn more than £250 million a

season with Manchester United leading the way at £433 million – or more than

five times as much as Hull. This really highlights the magnitude of the

challenge for the smaller clubs in the Premier League.

An incredible 81% of Hull’s revenue in the Premier League

came from television with just 14% from match day and 5% from commercial

income. This was very different to the more balanced revenue mix in the

Championship: broadcasting 48%, match day 34% and commercial 18%.

As Ehab Allam explained, “If you look at our income beyond

the Premier League money, I still don’t think we’re too clever. The other

income we get, commercial activity, gate receipts, is probably less than most

clubs in the division.”

Amazingly two Premier League clubs had an even higher

reliance on TV money than Hull with

Crystal Palace and Swansea City both earning around 82% of their revenue

from broadcasting, but this dependency is clearly not healthy.

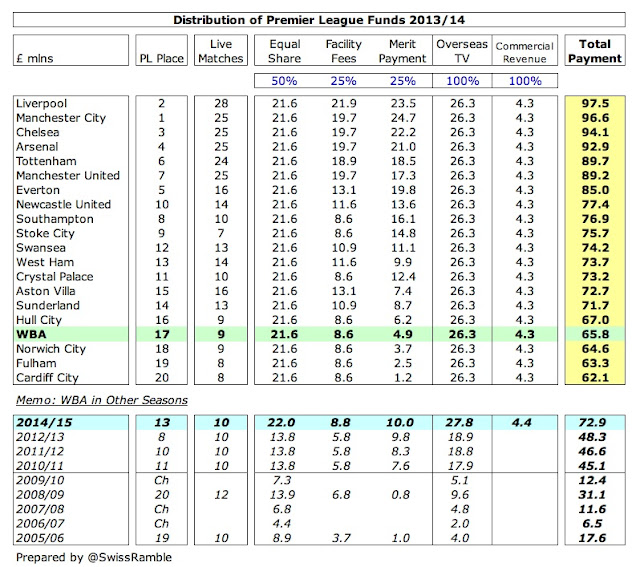

Hull’s share of the Premier League television money was £67

million in 2013/14. Most of the money is allocated equally, which means each

club receives 50% of the domestic rights (£21.6 million in 2013/14), 100% of the

overseas rights (£26.3 million) and 100% of the commercial revenue (£4.3

million). However, merit payments (25% of domestic rights) are worth £1.2

million per place in the league and facility fees (25% of domestic rights)

depend on how many times each club is broadcast live.

As a result, Hull’s merit payment for finishing 16th was

worth £6.2 million, while the Tigers’ distributions were also restricted by

being broadcast live just 9 times, though they were actually paid on the basis

of 10 times, which is the contractual minimum. This meant that they only got

£8.6 million, compared to, say, Aston Villa’s £13.1 million for being shown

live 16 times.

The sensational Premier League TV money is something of a

double-edged sword. On the one hand, the £62 million that Cardiff received for

being relegated was a lot higher than some major clubs received for winning

their respective leagues, e.g. Bayern Munich (£30 million), Atletico Madrid

(£34 million) and Paris Saint-Germain (£36 million). On the other hand, as Ehab

Allam pointed out, “It might be £67 million we’re getting, but if every club

gets that, how do you become competitive? Everything is relative.”

Of course, in 2015/16 Hull will receive a lot less TV money

in the Championship, amounting to around £28 million. This will comprise a

parachute payment of £25 million and a Football League distribution of £1.7

million plus some money for cup runs, live matches, etc. That will mean a

painful reduction in TV money of £40 million year-on-year.

That might sound horrific, but most clubs in the second tier

receive just £4 million from television, regardless of where they finish in the

league, comprising the £1.7 million from the Football League pool and a £2.3

million solidarity payment from the Premier League. Note: clubs receiving

parachute payments do not also receive solidarity payments.

Parachute payments are currently worth £65 million over four

seasons (£25 million in year 1; £20 million in year 2; and £10 million in each

of years 3 and 4) and have a big influence on a club’s finances in the

Championship.

Clearly, being in the Championship will have a major adverse

impact on Hull’s revenue. On top of the estimated £40 million fall in

broadcasting, there will also be reductions in match day and commercial. I

would expect match day to fall back by £4-5 million, assuming no lengthy cup

runs and lower average attendances; while commercial income is likely to drop

by £1-2 million to 2012/13 levels, depending on whether sponsorship deals have

relegation clauses.

That would produce a total reduction in revenue of £46

million from £84 million to £38 million, though this is still likely to be one

of the highest in the Championship next season. To place this into context, in

the Championship in 2013/14 QPR boasted the highest revenue with £39 million,

followed by Reading £38 million and Wigan Athletic £37 million.

There is also the opportunity cost of relegation, as there

will be even more money available in the Premier League when the next

three-year cycle starts in 2016/17 with the recently signed extraordinary UK

deals with Sky and BT producing a further 70% uplift. My estimate is that a

club that finishes 16th in the distribution table (as Hull did in 2013/14)

would receive around £101 million a season, which would represent an increase

of £34 million.

Match day income rose £6.1 million (104%) from £5.8 million

to £11.9 million, but this is a little misleading, as it includes £3.9 million

from the historic run to the FA Cup Final. Without this “bonus”, Hull’s match

day revenue would have been around £8 million, which would have been one of the

lowest in the Premier League.

Attendances have been higher in the top flight (around the

24,000 level) compared to the Championship, though this is still lower than

almost every other Premier League club, only ahead of Swansea City in 2013/14.

This is partly due to the 25,500 capacity of the KC Stadium,

but plans to expand this to above 30,000 were abandoned after the council

refused to sell the stadium freehold to the club. Allam understandably

protested that “nobody would build an extension on a house if they didn’t own

it”, but in fairness to the council they had built the ground with £43.5

million of public money.

This was part of the justification used for the 30% increase

in ticket prices for the 2014/15 season: “Due to stadium capacity, our home

attendances are the second lowest in the Premier League and with no plans to

increase the capacity of the KC, a price rise is the only viable option in

terms of increasing revenue from ticketing.” There will be a further price rise

of 6% in 2015/16, which seems a bit steep following relegation to the

Championship.

Commercial revenue rose £1.4 million (48%) to £4.5 million,

but this was still the lowest in the Premier League, behind Crystal Palace £6.9

million and Swansea City £8.3 million. It is easy to see why Allam is so keen on growing this revenue stream. Maybe it’s not a fair comparison, but

the big boys are in another league commercially with Manchester United leading

the way with a seriously impressive £189 million.

The club recently announced Flamingo Land, a North Yorkshire

based resort, as the new shirt sponsor for the 2015/16 season, replacing 12BET,

whose deal had been described by the club as the most lucrative in its history.

The two-year agreement was originally intended to run until the end of the

2015/16 season, but there was presumably a relegation escape clause. There was

also a new kit supplier with Umbro replacing Adidas in the 2014/15 season in a

four-year partnership.

Hull’s wage bill rose £17 million (67%) from £26 million to

£43 million, but the revenue growth meant that the wages to turnover ratio

significantly improved from a typical 153% in the Championship (no doubt

inflated by promotion bonus payments) to 51% in the Premier League. As well as

higher salaries in the top tier, there was an increase of 35 in the number of

players and coaches in 2014.

Despite this growth, Hull’s wage bill of £43 million was

still the lowest in the Premier League in 2013/14, behind Crystal Palace £46

million, Norwich City £50 million and Cardiff City £53 million. There then

comes a whole bunch of clubs in the £60-70 million range before we get to the

elite clubs.

There is a strong correlation between wage bill and sporting

success, so it is perhaps not a surprise that Hull have struggled, though it is

likely that their wage bill will have been higher in 2014/15 following the

major recruitment last summer (though bonuses for staying up will be lower).

Similarly, Hull’s wages to turnover ratio of 51% is also one

of the lowest/best in the Premier League, about the same as one of the other

clubs promoted in 2013, Crystal Palace. However, the other club promoted that

season, Cardiff City, had a much worse ratio of 64% and went straight back

down, so spending is not always a guarantee of success.

The Allams are paid via management charges from their

company Allamhouse Limited. Although these charges went up from £112,000 to

£165,000 in 2013/14, this is still a relatively low sum compared to many other

clubs.

The wage bill will be substantially lower in the

Championship due to relegation clauses, as outlined by Steve Bruce: “Everybody

concerned takes a huge reduction in salary. The club has had a really stringent

policy, so that if we do get relegated, it does not fall into drastic times

which a lot of clubs do. Most players take a 40-50% reduction in their salary.”

Of course, the quid pro

quo is that these players also have a reasonable buy-out clause in

their contracts, so it is easier for them to leave.

Net debt was cut by £7.4 million from £72.2 million to £64.8

million, as gross debt was reduced by £5.6 million from £72.9 million to £67.3

million, while cash balances rose £1.8 million from £0.7 million to £2.5

million. The debt is entirely owed to Allam’s company with no external bank

loans or overdrafts outstanding. The club’s financial problems required an

immediate £41 million loan from the owners in 2010/11 and the debt to the owner

has risen by £26 million since then.

In addition, Hull owe £13.5 million of transfer fees to

other clubs and have £3.4 million of contingent liabilities to players

depending on number of appearances and results.

Hull are mid-table in terms of debt in the Premier League,

but this has almost certainly increased in the 2014/15 season with the club

noting that “new signings costing in excess of £47 million have been made”

after the accounts closed. Some have speculated that the debt could be as high

as £100 million now, but this will only be revealed once the 2014/15 accounts

are published. As long as Allam is happy, this should not be a problem, but it

is a worrying amount of debt to take into the Championship.

Unlike many other football club owners, Allam charges around

5% on his loans, which has amounted to around £3 million interest paid in each

of the last two years. This is by no means the highest in the Premier League,

as Manchester United pay £27 million following the Glazers’ leveraged buy-out

and Arsenal pay £13 million for the Emirates Stadium financing, but it is a

relatively large burden for a club of Hull’s size.

The cash flow statement highlights the changes in Hull’s

approach and the issues that the club now faces after relegation. As a rule,

Hull have negative cash flow from operating activities – unless they are in the

Premier League. These shortfalls plus any expenditure on player purchases have

been covered by loans from the Allams, which got as high as £72 million in

2013.

This is not a problem, so long as Allam does not turn the

taps off. When asked about this possibility, his answer was interesting, “It is

a lot of money I have put in. So far I am comfortable with it, as long as we

are achieving results.” Relegation must therefore be a cause for concern, as

that is by definition not achieving results.

It is also a little strange that the Allams were so quick to

reduce their commitment once the money started to flow from the Premier League.

Ehab noted, “Whatever we’ve made has been put back into the squad. As you can

see, we’re not here to make money for ourselves.” That may well be true, but

their debt was reduced by £4.7 million in 2013/14.

Just to add to Hull’s challenges, they have been fined

€200,000 by UEFA for not being compliant with Financial Fair Play (FFP)

regulations. They will have to pay an additional €400,000 if their accounts are

not in order for the 2015/16 season. In fairness, this is harsh on Hull, as

they were only investigated after qualifying for the Europa League and had

little chance to compensate for the large losses in the Championship.

"The drugs don't work"

One minor success story is the academy, which has achieved

the appropriate standard to be awarded Category Two status, but even this is

not without controversy, as this was helped by building an indoor 3G pitch in

the Airco Arena for the academy’s exclusive use, which meant that a number of

community sports groups that had been using the facility were told to leave.

The big question now is whether Allam will still want to

continue as chairman and owner. From a purely financial perspective, this will

be increasingly difficult, as the man himself outlined: “I cannot keep throwing

money into it. There must be a limit. Our target is for the club to be

self-finance, relying on its own resources.” This will be easier said than done

in the Championship.

He may well also walk away now that the FA has again blocked

his proposal for a name change. He actually did put the club up for sale in

April 2014 the first time that his request was denied, but has not found the

right investor yet: “not the quality buyers I would sell to.” Of course, after

relegation the club is a less attractive prospect, so the price would have to

come down accordingly.

"Ground Control to Major Tom"

In many ways, Allam is a good owner for Hull City, as he

explained: “I am a Yorkshireman, I came here more than 40 years ago, yet they

still call me a foreign owner. I have never used the football club to make

money for myself, I don’t need it. If you go to the stadium, there is not a

single mention of me or my company. I saved this club from administration,

because I believe that was the best thing I could do for this city. Football is

vital to the community. I wanted to give something back. Businessmen should

look after their community.”

If only he could resist the temptation to change the club’s

name and avoid putting his foot in his mouth when engaging with the fans, he

would almost be the perfect owner. He’s a mixture of good and bad, but nothing

is ever completely black and white (or should that be amber?) in the world of

football.

In the meantime, Allam has effectively paid nearly £70

million for the club to stand still. His son Ehab admitted, “We’re financially

strong as long as you make the assumption we stay in the Premier League”, and

that has obviously not happened.

"Don't bring me down, Bruce"

Steve Bruce said that the objective was “to compete at the

top end of the Championship and bounce straight back into the top flight”, but

this will be a severe challenge in one of the most competitive leagues around.

He has already lost a number of key squad players, including

Stephen Quinn, Tom Ince, Paul McShane, Liam Rosenior, Maynor Figueroa, Steve

Harper and Yannick Sagbo, while others are surely in the departure lounge,

including Nikica Jelavic, Dame N’Doye, Mo Diamé and Robbie Brady.

Bruce will certainly need to recruit to have any chance of

promotion. Either way, it is difficult to disagree with Michael Dawson’s view

that “it is going to be a slog in the Championship.”