By most people’s standards Milan have just enjoyed a pretty good season. They were runners-up in the league, only behind an undefeated Juventus; they reached the quarter-finals of the Champions League before being eliminated by the mighty Barcelona; and lost in the semi-finals of the Coppa Italia. However, it was still a disappointment, as they had established a healthy lead in the race to the scudetto, and it was a backward step compared to the previous season, when they had won Serie A for the 18th time.

Last year’s triumph was particularly noteworthy, as it was

under the guidance of the previously unheralded Max Allegri, who won the title

in his first season – just like his more famous predecessors Arrigo Sacchi and

Fabio Capello. However, this year Milan have been plagued by injuries, losing

the likes of Mathieu Flamini, Antonio Cassano, Alexandre Pato, Thiago Silva and

Kevin-Prince Boateng for lengthy periods. As their talisman Zlatan Ibrahimovic

lamented, “Injuries have followed us for the whole season.”

Ibra himself had done his utmost to secure another title for

the rossoneri,

as his 28 league goals earned him the capocannoniere

(top scorer) award for Serie

A, though this was not enough to continue his remarkable record of

gaining a league winners’ medal every season since 2003 (with Ajax, Juventus,

Inter, Barcelona and Milan).

"Partial to your Ibracadabra"

However, whether it was down to injuries, second season

syndrome for Allegri or the simple fact that the team was not quite good

enough, the fact remains that Milan did not win any silverware – unless you

count the 2011 Supercoppa,

the curtain raiser to the new season. “Close, but no cigar” is not good enough

for a side that has a fantastic record in winning trophies, including the

Champions League on an incredible seven occasions (only bettered by Real

Madrid) and the European Cup Winners’ Cup twice.

No matter how impressive Milan have been in the past – and

they can lay claim to having the best side of all time under Sacchi – they are

now facing daunting challenges, both on and off the pitch.

Many of the old guard have left the club this summer,

including the elegant defender Alessandro Nesta, the prolific Pippo Inzaghi,

the tigerish Rino Gattuso, Mark Van Bommel and Gianluca Zambrotta. In addition,

there are question marks over the veteran Clarence Seedorf, who is mulling over

a one-year extension, and the club has not exercised loan options for Maxi

Lopez and Alberto Aquilani (though the latter may yet sign on a reduced

package). That’s a lot of experience to try to replace in one fell swoop.

"Allegri - Mad Max"

This mission is made more difficult by Milan’s financial

situation, which is by no means disastrous, but is bad enough to give the club

pause for thought. Their traditional modus

operandi has been to operate with substantial losses, which are then

covered by the owners, but this will not be possible in the new world of UEFA’s

Financial Fair Play (FFP) rules where clubs will have to live within their

means without the assistance of a wealthy benefactor.

This will test to the limit the negotiating skills of

Milan’s vice-president Adriano Galliani, who has proved himself to be a wily

old fox in the past, especially when he snapped up Ibrahimovic from Barcelona

for around a third of the price that the Catalans paid a year before. The need

for Milan to find bargains was further emphasised this summer when they signed

two international midfielders on Bosman free transfers: Riccardo Montolivo from

Fiorentina and Bakaye Traoré from Nancy.

Ibrahimovic of all people highlighted the club’s financial

woes, “Milan’s problem is economic. There is no money to buy five players, or

even the ones we need. We made a couple of signings, maybe there will be a

third.”

When you look at the club’s most recent accounts (for the

year up to 31 December 2011), you begin to understand what the big Swede is

talking about, as these reported a thumping great loss of €67.3 million.

Amazingly this actually represented a slight (€2.4 million) improvement on the

previous year’s loss of €69.8 million, an indication of Milan’s structural

weaknesses. The losses in both years would have surpassed €80 million without

the benefit of substantial tax credits, €15.7 million in 2010 and €13.3 million

in 2011.

Revenue grew by 7% to €234.8 million, but this was matched

by a €13.7 million increase in the wage bill to €206.5 million, a record high

for Milan. Note that this definition of revenue excludes €23.6 million profit

on player sales and €8.4 million increase in the value of fixed assets (shown

elsewhere). If these are added back, we get the €266.8 million of revenue

mentioned in the club’s press release.

This produced operating an operating loss of around €100

million level for the second consecutive year, which is distinctly

uncomfortable for a club aiming to be self-sufficient in the near future.

I should clarify that this analysis is based on the accounts

for the consolidated Milan Group, as opposed to just the football club AC Milan

SpA, as these are the accounts that will be used for UEFA’s FFP review. The

group accounts include Milan Entertainment SpA and Milan Real Estate SpA, but

there is not a significant difference. In fact, the loss of €67.3 million for

Milan Group is €8.2 million better than the €75.5 million registered by AC

Milan SpA.

Milan’s poor financial performance is nothing new. The last

time that the club made money was 2006 and even then the €11.9 million profit

was heavily influenced by once-off factors, namely the €40 million profit from

selling Andriy Shevchenko to Chelsea and a €27 million once-off payment for an

option on future TV rights. Since then, there have been five consecutive years

of losses, adding up to a combined deficit of around a quarter of a billion

Euros.

The only recent year that looks good on paper is 2009, when

the loss was “only” €9.8 million, but this was almost entirely due to the hefty

€74 million profit on player sales, arising from the transfers of Kaká to Real

Madrid and Yoann Gourcuff to Bordeaux. As we have seen, it is difficult, if not

impossible, to raise similar sums form player sales every year, not to mention

the detrimental effect it would have on the team.

In each of the last two years Milan have generated €23-24

million from this activity, much of which has been derived from the special

relationship that they appear to have with Genoa, who have contributed over €30

million in this period, including €17 million in 2011: Alexander Merkel €9.9

million, Nicola Pasini €3.3 million, Mario Sampirisi €2.0 million and Sokratis

Papastathopoulos €1.8 million.

One more technical point: for profits on player sales I take

the plusvalenze

less the minusvalenze

to give a net figure, e.g. in 2011 €23.6 million minus €0.3 million (to release

Onyewu Oguchi) gives the €23.3 million in my schedule.

If we exclude tax movements and profit from player sales,

then the adjusted loss for Milan over the last four years would add up to a

colossal €386 million with three of those four years coming in over the €100

million mark. In other words, with the sale of a world class player Milan make

losses; without such a sale they make large losses.

Of course, Milan are not the only leading Italian club to

find themselves in this situation. Indeed, in 2010/11 the losses were even

higher at Juventus (€95.4 million) and Inter (€86.8 million). The big three

contributed 89% (€252 million) of the total Serie

A losses of €285 million. Note that I have used Milan’s 2010 loss in

this schedule to be consistent with a survey prepared by La Gazzetta dello Sport,

but the loss is around the same level in any case.

More encouragingly for Italy’s top flight is that the number

of clubs making a profit in 2010/11 doubled from the four in the previous

season to eight (Bari, Lazio, Palermo, Catania, Napoli, Udinese, Parma and

Brescia). This list includes two clubs that qualified for the Champions League

(Napoli and Udinese), so sound husbandry of a club’s finances need not

necessarily mean lack of success, though it should be acknowledged that some

did benefit from substantial player sales.

Over the last three seasons it has been more or less the

same story of colossal losses at both Milan clubs, who are by some distance bottom

of Italy’s profit league. Juve’s losses over the period are virtually all

because of 2010/11, mainly due to not qualifying for the Champions League and

investing in their new stadium, while Milan and Inter’s figures have been

consistently poor. At least Milan win the financial Derby della Madonnina with Inter’s

astonishing losses of €310 million in this period being more than twice Milan’s

€146 million. In truth, neither club has much to write home about on this

topic.

But surely all the top football clubs lose money, right?

Actually, that’s not really the case, as a few did report profits in 2010/11:

Real Madrid made a sizeable €47 million, thanks largely to their enormous

revenue; Arsenal €14 million, boosted by property sales; and Manchester United

€11 million, as their awesome cash generating capacity was enough to cover

interest charges on their massive debt. Bayern Munich only recorded a small

profit of €1 million, but this represented their 19th consecutive year of

profits. Even big spending Barcelona’s loss was relatively small at €9 million.

Of course, some leading clubs abroad also employ the sugar

daddy model, such as Champions League winners Chelsea, who made a loss of €75

million, while Manchester City’s attempt to gatecrash the party cost them €219

million. Even so, it is clear that Juventus, Inter and Milan all face more

serious issues compared to the others, as their ability to generate additional

revenue in the short-term is more constrained.

That said, Milan’s revenue is not too shabby by Italian

standards. In fact, for 2010/11 (the last season when all clubs have published

accounts), their revenue of €220 million was the highest with only Inter

anywhere near them (€211 million). The other clubs were miles behind with only

three others earning above €100 million: Juventus €154 million, Roma €144

million and Napoli €115 million. This is despite the leading lights effectively

transferring some of their revenue to the others after the collective TV deal

was implemented.

However, as John Donne said, “No man is an island” and Milan

also have to look beyond their borders at other European clubs. At first

glance, Milan appear to be sitting pretty at seventh place in Deloitte’s Money

League, but problems begin to emerge on a closer inspection, as they are a long

way short of their peers abroad. In particular, the Spanish giants generate

significantly more revenue with Real Madrid (€479 million) and Barcelona (€451

million) earning around twice as much as Milan, benefiting from huge individual

TV deals.

Both Manchester United (€367 million) and Bayer Munich (€321

million) earn around €100 million more than the rossoneri,

the English taking advantage of significantly higher match day revenue, while

the Germans’ commercial expertise puts everyone else to shame. In fact, at the

latest exchange rates United would also break the €400 million barrier. This

vast revenue discrepancy makes it difficult to compete, especially when that

shortfall in turnover occurs every year.

Eagle-eyed observers will have noticed that Milan’s revenue

figure of €235 million is different to the €253.2 million included in the

club’s accounts for 2010. There are two reasons for this. First, in order to be

consistent with other countries, Deloitte excludes: (a) player loans €0.5

million; (b) profit from player sales €25.5 million; (c) change in asset values

€7.6 million. Adding those to the €220 million shown in my analysis gives the

€253.2 million reported in Italy.

Second, Milan’s accounts cover a calendar year (up to 31

December), while the majority of clubs’ figures coincide with the football

season, so the accounting close is in June. Because of this anomaly, Deloitte

adjust Milan’s figures based on information provided by the club, leading to

the €235 million in their league table.

Regardless of all these technical adjustments, the

underlying themes for Milan (and Italian football) are very much the same. A

recent report from the Italian Football Federation (FIGC) concluded, “The

current business model is difficult to sustain and not very competitive.” Its

president, Giancarlo Abate, noted that in particular match day income,

sponsorships and merchandising were in need of urgent attention to reduce the

reliance on TV money.

These problems have been reflected in the lack of revenue

growth of Italian clubs. Since 2005 Milan have managed to grow their revenue by

just €20 million (9%), which is only ahead of Juventus among leading European

clubs. In that period they have been overtaken by Barcelona, Bayern Munich and

Arsenal. Most strikingly, Barcelona’s revenue was €7 million lower than Milan

in 2005, but is now far over the horizon at €216 million higher, while the

investment in new stadiums at Bayern and Arsenal has really paid dividends. As

Galliani put it, “Twenty years ago Milan invoiced more than Real Madrid, today

only half. That’s the real problem.”

Essentially, Milan’s revenue has been flat for the last few

years, though this disguises two opposing factors: TV revenue has fallen by €29

million since 2006 to €114 million, largely due to the move to a collective

deal, while commercial income has increased by €23 million to an impressive €91

million.

Match day revenue has also risen by €3 million, though it

remains a feeble €29 million, just 13% of total revenue, which, in fairness, is

typical of all Italian clubs and helps explain their relative revenue weakness.

Despite the decline in TV revenue, it is still the most important revenue

stream, accounting for just under half of Milan’s revenue. This is partly due

to the higher payout from the Champions League, which rose €16 million in 2011,

more than offsetting the €7 million fall in domestic TV money.

The €114 million earned from television in 2011 comprised

€78 million from the domestic deal and €36 million from the Champions League (a

combination of the last 16 in 2010/11 and the group stage in 2011/12). They

received the third highest domestic money, just behind Juventus and Inter, but

a fair bit more than other Italian clubs, e.g. Napoli and Roma got around €60

million; Lazio about €50 million; and Fiorentina, Palermo and Udinese around

€40 million.

This represents an improvement for mid-tier clubs following

the implementation of the new collective agreement in 2010/11. Under the new

allocation, 40% is divided equally among the Serie

A clubs; 30% is based on past results (5% last season, 15% last 5

years, 10% from 1946 to the sixth season before last); and 30% is based on the

population of the club’s city (5%) and the number of fans (25%).

The result is a reduction at the top end, so Galliani is not

a happy customer, “In football big teams have to share income with other sides

and this is an anomaly.” This may be a bitter pill to swallow, but it has been

sweetened by the distribution formula, which still favours the top clubs to an

extent with the allocations based on historical success and number of fans.

Even now, Milan’s TV income is the sixth highest in Europe.

Furthermore, the decrease would have been even higher if the

total money negotiated in the new deal had not been 20% higher than before at

around €1 billion a year. This cemented Italy’s position as the second highest

TV rights deal in Europe, only behind the Premier League, but significantly

ahead of the other major leagues, despite the Bundesliga

increasing its rights by over 50% for the next four-year deal. The new French

contract has actually fallen from €668 million to €612 million, considered a

good result in this harsh economic climate.

As you might expect for a club with media magnate Silvio

Berlusconi at the helm, television income has always been important to Milan,

climbing as high as €140 million in 2007, the highest in Europe, partly due to

a sensational domestic deal, but also thanks to the payment received for

winning the Champions League.

Qualification for the Champions League is imperative for

Milan with the accounts identifying this as a key risk for the club’s economic

prospects. This can be seen in 2008/09, when Milan earned just €0.4 million

from the UEFA Cup, compared to €25.8 million from the Champions League in

2010/11. This was made up of €7.2 million participation fees, €2.4 million for

performances in the group (2 wins at €800k plus 2 draws at €400k), €3 million

for reaching the last 16 and €13.2 million from the TV (“market”) pool.

The money received for 2011/12 should be much higher: (a)

Milan progressed further (to the quarter-finals); (b) they will receive more

from the TV pool, as they won Serie

A in 2010/11 (half is allocated based on finishing positions in the

previous season’s domestic league).

The size of the prize is now enormous, as we can see from

the finalists in 2010/11 (Barcelona and Manchester United) each receiving over

€50 million, not including additional gate receipts or increases in sponsorship

payments. Financially, the Europa League provides little compensations, with

the four Italian clubs only receiving around €2 million each.

Furthermore, there has been talk in the English media of

Champions League revenue significantly increasing in the next three-year agreement, citing

David Taylor, UEFA Events’ chief executive, “We have at least achieved

triple-digit growth.” Unfortunately the Italian league has lost a place to the Bundesliga, due to

lower coefficients, so now only the top two teams in Serie A are assured of direct entry,

while the third-placed team goes into the preliminary qualifying round.

The most glaring revenue weakness for Milan is match day

revenue. Even though this is the highest in Italy at €36 million (ahead of

Inter €33 million, Napoli €22 million and Roma €18 million), it is dwarfed by

major clubs in other countries, especially England. Chelsea earn more than

twice as much €81 million, while Manchester United €130 million and Arsenal

€112 million generate around three times Milan’s figure. Granted, they have

staged more home games, but United earn €4.5 million a match compared to

Milan’s €1.4 million.

Although Milan have the highest average attendance in Italy

of 51,400, this was a 4% reduction from the previous season and means that only

64% of the stadium’s capacity was filled. In fact, Milan’s crowds have dropped

significantly from the 64,500 average achieved in 2002/03. In fairness, this is

a generic problem in Italy, where total attendances in Serie A have slumped from 9.4 million

in 2008/09 to 8.9 million in 2010/11 (per the FIGC), despite low ticket prices, due to a combination of

obsolete stadiums, poor views and, let’s be frank, the suspicion of match fixing.

This is why Milan have been exploring opportunities for

moving to a new stadium that could maximise their revenue earning potential.

It’s not just that the club currently pay the council over €4 million rental a

year under a 30-year lease ending in 2030, but the lack of ownership means that

they miss out on profitable opportunities like premium seating, corporate

boxes, restaurants, retail outlets, naming rights and non-sporting events. As

Galliani explained, “A new stadium is essential for a club that wants to

compete in the future. Look at Bayern Munich: since they built a new stadium,

their revenue has increased by €60 million.”

Closer to home, Juventus have just moved into a fabulous new

arena, but are the only leading Italian club to own their stadium. Although it

cost them around €150 million to build, much of the funding was sourced from

innovative deals, e.g. 60% of the money was derived from a naming rights deal.

Milan would undoubtedly require substantial funds to do the same, but the

benefits would be substantial, e.g. Juventus believe that their match day

revenue will at least double,

Galliani recently revealed that the club had tried to buy

San Siro, but the price quoted by the council was too high, so they have

instead turned their attention to modernising the ground in order to develop an

“elite stadium”, ready for the 2015 Champions League final. However, he

admitted that this was not ideal, due to “the problems that follow when you

share it with another club.” Any new development will be a long-term project,

e.g. even Juve’s new stadium took more than 10 years to complete after the

first discussions with their local council.

"Silva and Gold"

It had been hoped that new stadiums would be developed as

part of Italy’s bid for Euro 2016, but unfortunately this was lost to France,

as was the catalyst for government intervention. Galliani warned, “Germany have

overtaken us thanks to the wonderful new stadiums they built for the World Cup

in 2006. Thanks to the new stadiums being built for Euro 2016, I predict that the

French will also overtake us.” This is why Italian owners hope that new laws

will be introduced to facilitate new stadium construction.

Whatever the solution, something must surely be done, as

this massive revenue shortfall means that Milan are not competing on a level

playing field, especially with the advent of FFP. As Galliani lamented, “The

rankings for revenue and sporting success tend to coincide. The gap comes from

different points of departure: in the case of Milan the gate receipts do not

reach €30 million a year.”

Where Milan have really begun to motor is in their

commercial operations, as revenue here has really taken off in the last two

years, rising by €10 million (13%) in 2011 alone to €91 million. This is not

only the highest in Italy by some distance (Inter and Juventus are the closest

challengers at €54 million apiece), but is also the fifth highest in Europe.

That said, Milan still only earn half as much as Bayern Munich’s astonishing

€178 million and are a long way behind Real Madrid’s €172 million and

Barcelona’s €156 million.

Commercial revenue was inflated by once-off payments in 2009

and 2010: the former contained €20 million for the sale of Milan’s image

archive, while the latter included €5 million for the sale of some apartments. Excluding

these once-off items, the underlying growth since 2009 has been a very

impressive 50%, partly due to the partnership with Infront, who handle all

sponsorships except kit deals. Progress can be measured by the raft of new

sponsors signed up in the last 12 months, including Taci Oil, Indesit, United

Biscuits and Nivea for Men.

Milan have long-term deals with their shirt sponsor and kit

supplier. The Emirates contract runs until 2015 and is worth a guaranteed €12

million a season plus performance related bonuses (€2.7 million in 2011), while

the Adidas kit deal has been extended to 2017, generating €17.5 million last

year, including a €1 million performance bonus.

These deals compare pretty favourably with those at other

Italian clubs (a) shirt sponsors: Inter – Pirelli €12 million, Juventus –

BetClic €8 million, Napoli – Lete €5.5 million and Roma – Wind €5 million; (b)

kit suppliers: Inter – Nike €12 million, Juventus – Nike €12 million, Roma –

Kappa €5 million and Napoli – Macron €4.7 million.

However, these agreements are still worth much less than

those at foreign clubs, e.g. Manchester United, Barcelona, Real Madrid,

Liverpool, Bayern Munich and Manchester City all have shirt sponsorships worth

more than €20 million a season. Similarly, the first four of those clubs have

penned kit supplier deals for over €30 million a year,

Milan reportedly sell between 400,000 and 600,000 shirts a

season, which would put them in the top ten clubs worldwide and around the same

level as Inter and Juventus, though the likes of Real Madrid and Manchester

United sell nearly three times as many. The rossoneri

are now looking to make more from global opportunities, e.g. this summer they

will play prestigious friendlies against Real Madrid and Chelsea in the United

States.

Fundamentally, the most important challenge for Milan is the

wage bill, which rose €14 million in 2011 to a totally unsustainable €206

million. Even though most of this increase was due to higher bonuses for

winning the scudetto

in 2011, the fact remains that this is the highest wage bill in Milan’s history

and the second highest ever for Serie

A, only surpassed by the €234 million paid out by Inter in their

2009/10 treble winning season.

Since 2006 wages have grown by 50% from €138 million to €206

million, while revenue has actually decreased by €3 million in the same period,

leading to a rise in the important wages to turnover ratio from 58% to 88%.

This is much worse than UEFA’s recommended maximum limit of 70%, though Milan

are far from alone in struggling to confront this issue in Italy, as seen by

Juventus (91%) and Inter (90%).

In Italy only Inter come anywhere near Milan’s wage bill. In

2010/11 they were just behind Milan’s €193 million with €190 million, while the

next highest were Juventus €140 million and Roma €107 million. To place Milan’s

wage bill into context, it is around the same as Fiorentina €55 million, Genoa

€52 million, Napoli €52 million and Lazio €39 million combined. An analysis by La Gazzetta last

summer suggested that the cost of Milan’s first team squad of €160 million was

far above Inter’s €145 million, but it’s far from certain that their figures

are accurate.

Milan’s wage bill also looks excessive in comparison with

foreign clubs, only surpassed by Barcelona €241 million (including other

sports), Real Madrid €216 million, Manchester City €209 million and Chelsea

€202 million. Strikingly, it is higher than Manchester United and Bayern

Munich, who have been more successful recently. It is also apparent that most

of these clubs have a much better wages to turnover ratio than Milan, because

of their higher revenue, e.g. Real Madrid 45%, Manchester United 46%, Bayern

49% and Barcelona 53%.

Galliani has recognised the problem, “Both Fininvest and I

are trying to reduce the amount of money spent on wages.” However, we have

heard this before. Last year, he said, “Milan absolutely have to reduce the

wage bill. It is difficult to increase revenue, so we have to act on the

salaries and hope that the players understand, especially with financial fair

play.” The problem is that it is difficult to cut the wage bill without

reducing the competitiveness of the squad.

That said, Allegri appears to be on message, “We had 33

players in the squad this season, but that was because we had to make some

adjustments in January because of injuries. We’ll have a 25-26 man squad,

including three goalkeepers, for the new season.” Many senior players have left

this summer, while others will be only be given contract extensions on reduced

terms, e.g. Flamini has reportedly been offered €1.75 million instead of his

current €4 million, while any offer to Aquilani will also be much lower. Using

salary figures from La

Gazzetta, the gross saving would be at least €30 million. Clearly

some players will need to be replaced, but the cost should be much less, e.g.

Van Bommel and Gattuso were both costing €7 million.

The other element of player costs, namely amortisation, has

also been rising, having doubled from €22 million in 2006 to €45 million in

2011, though it is still lower than Inter €52 million and Juventus €47 million

– and miles behind a big spender like Manchester City €101 million. In

addition, the club has written-down €9 million in player values in the last two

years for the sales of Ronaldinho and Ricardo Oliveira.

As a reminder, amortisation is the annual cost of

writing-down a player’s purchase price, e.g. Ibrahimovic was signed for €24

million on a 4-year contract, but his transfer is only reflected in the profit

and loss account via amortisation, which is booked evenly over the life of his

contract, i.e. €6 million a year.

This growth is a reflection of Milan’s activity in the

transfer market, which can be divided into three periods in recent times.

First, the boom time with €237 million net spend in the four years up to 2003;

then the age of austerity with net sales proceeds of €18 million in the seven

years up to 2010, when Milan had to “sell before we can buy” per Galliani;

finally a return to investment with net spend of €51 million in the last two

years.

Milan might be shopping at the cheaper end of the market,

e.g. Stephen El Shaarawy for €10 million and Kevin-Prince Boateng for €7.5

million, but this has still been enough to make them the third highest spenders

in Serie A

during this period, only beaten by Juventus €101 million and Roma €58 million.

The annual deficits have resulted in net debt doubling in

the last five years to stand at €292 million, comprising €156 million of bank

loans plus €136 million owed to factoring companies based on future income.

Most of this is short-term debt, but is supported by a €390 million line of

credit from Fininvest. On top of that Milan owe other football clubs €30

million, mainly €16 million to Barcelona for Ibrahimovic and €10 million to

Manchester City for Robinho, though are themselves owed €16 million by other

clubs.

In fairness to Milan, this is a problem throughout Italy

with La Gazzetta

complaining that clubs were “buried under a mountain of debt”, following the

14% increase last year to €2.6 billion, but it is worth noting that Milan’s

debt breaches one of UEFA’s warning indicators, as it exceeds 100% of revenue.

In fact, Milan’s balance sheet is the weakest in Serie A with net

liabilities of €77 million, even after an improvement from €97 million the

previous year. This is a little misleading, as the value of the players in the

accounts of €136 million is smaller than their worth in the real world (€271

million according to Transfermarkt),

but it is nevertheless an indication of the club’s financial fragility.

This has necessitated the support of the owners with

Fininvest pumping in €210 million in the last five years, including €87 million

in 2011 alone (plus a further €25 million in March 2012). As Galliani put it,

“The losses have been completely covered by Fininvest. I thank the president

for his passion. Without Fininvest, we couldn’t be an example of sporting

excellence the world over.” Berlusconi wryly echoed these thoughts in a message

to new Roma owner Thomas DiBenedetto, “You spend lots of money and earn

nothing.”

Although the cash flow statement suggests that Milan are

fine at an operating level, the reality is that they cannot afford to purchase

players without increasing debt and/or additional funding from the owners.

Incidentally, player purchases are much higher in cash terms than has been

reported in the media, presumably due to the nature of some of the rights

sharing deals with Genoa.

These difficulties have raised the prospect of Berlusconi

selling Milan, especially as Fininvest is not exactly thriving in today’s tough

economy, exacerbated by the €560 million fine following a court ruling that it

bribed a judge during the Mondadori takeover battle. His daughter Barbara, who

joined the board in 2011 “to reaffirm and strengthen the tie between the team

and the family”, has said that her father has no intention of moving on, but

there has been talk of selling a 40% stake to an overseas investor, though they

might be put off by the stadium issue.

Even if Berlusconi did want to return to the good old days

with a few extravagant purchases, he needs to be mindful of UEFA’s Financial

Fair Play regulations, which will ultimately exclude from European competitions

clubs that continue to make losses.

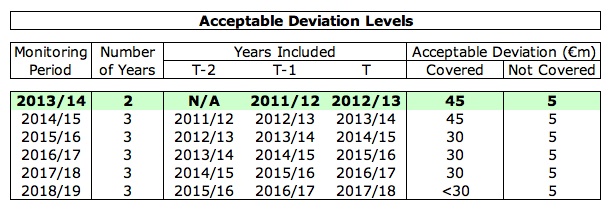

Fortunately for Milan, all of the losses made to date are

not considered for FFP, but they have to get their act together immediately, as

the first monitoring period will taken into account losses made in 2012 and

2013. However, they don’t need to be absolutely perfect, as wealthy owners will

be allowed to absorb aggregate losses (“acceptable deviations”) of €45 million,

initially over two years and then over a three-year monitoring period, as long

as they are willing to cover the deficit by making equity contributions.

Getting to break-even will be an arduous task for Milan,

because they will need to radically overhaul their strategy, as conceded by

Galliani, “FFP hurts Italy. There will no longer be patrons that can intervene.

Until now people like Berlusconi and Moratti would be able to support us, but

with the fair play it will no longer be possible.”

"Duck Rock"

Barbara Berlusconi underlined the need for change, “Soccer

teams will have to transform into proper companies. If you can only spend what

you get, then you have to keep costs in check and increase revenue. It’s a

challenge that can become an opportunity.” That’s undoubtedly true, but, given

Milan’s limited scope to increase revenue, that effectively means cutting the

wage bill, which Galliani accepted, “No question, we’ll need to reduce our

expenses.”

Alternatively, Milan could boost profits by selling players

and both Thiago Silva and Ibrahimovic are much in demand, though the dilemma

was neatly summarised by club legend Paolo Maldini, “If you want to win

something, then you can’t do without them. If the objective is to balance the

accounts and have a decent campaign, then you can sacrifice one of the two.” On

the other hand, the club might be willing to listen to offers for Robinho or

Pato, who are not indispensable.

"KPB - a prince among men"

In a certain sense FFP might actually point the way forward

for Milan, as the break-even analysis excludes costs for stadium development

and the youth academy. The latter has proved a little disappointing in recent

years, especially when you consider that Milan’s greatest teams have always

included many in-house products like Franco Baresi, Billy Costacurta and that

man Maldini, but Galliani only last week stressed the importance of youth

players breaking into the first team.

Right now, Milan will need to show some fancy footwork to

improve their finances, while maintaining their ability to challenge at the

highest levels. Ibrahimovic has already voiced his disquiet about the change in

direction, “There used to be a great Milan project, now we’ll have to see if

they take it forward”, but the Berlusconi-Galliani axis really don’t have too

many options. If they do manage to pull this off, then we will have to accept

that the devil really does have all the best tunes.