At the beginning of the 2014/15 season very few analysts

expected Lyon to be among the front-runners in Ligue 1, given that they had

just changed their manager, replacing Rémi Garde with Hubert Fournier, and

spent virtually no money. However, their exciting young side led the table for

a lengthy period before finishing in a highly creditable second place behind

the expensively assembled Paris Saint-Germain, thus qualifying for the

Champions League.

Expectations were on the low side, as Les Gones had

endured much disappointment in the previous two seasons, failing to reach their

previous heights by only finishing 3rd and 5th in the league. This might not

sound too bad, but remember that Lyon had won the league seven times in a row

between 2002 and 2008.

They had also enjoyed 12 consecutive participations in the

Champions League, but their recent European adventures have been restricted to

the Europa League. It is true that they reached the quarter-finals of this

competition in 2013/14 before being eliminated by Juventus, but last season

they did not even manage to get past the qualifying stages.

After Lyon’s many years of success, based on a “buy low,

sell high” model skillfully executed by their respected chairman Jean-Michel

Aulas, the club decided to change their strategy in an attempt to move to the

next level: “Our ambition is to move closer to the major European clubs, by

putting priority on investment rather than an immediate net profit.”

"Come on, Alex, you can do it"

Initially, the plan seemed to be working as Lyon reached the

Champions League semi-final for the first time in 2010, but ultimately the

inflated spending on the likes of Yoann Gourcuff, Lisandro Lopez, Aly Cissokho,

Michel Bastos and Bafetimbi Gomis spectacularly backfired. Far from elevating

the club to elite level, this approach plunged Lyon into disarray.

The financial challenges posed by the over-expenditure have

been exacerbated by the money invested in building a new stadium. While this

will make a significant, positive difference to Lyon once it is finished in

early 2016, it has been a substantial drain on resources and will end up

costing more than €400 million.

Nor have Lyon been helped by the arrival of wealthy new

owners at Paris Saint-Germain in 2011. The influx of Qatari money has produced

an uneven playing field, so it is no great surprise that PSG have dominated the

French league, winning the title for the last three seasons. To a lesser

extent, it is a similar story at Monaco.

These difficulties have forced Lyon to change track again

and they are now focusing on youth in a quest to cut costs. The club’s recent

financial performance emphasises why they need to follow a more sustainable

strategy, as they have reported a series of hefty losses. In 2013/14, the last

season for which we have annual published accounts, the club made a pre-tax

loss of €28 million (€26 million after a tax credit).

As Aulas somewhat drily commented, “We were not able to

achieve our objective and return to break-even.” In fact, the result was £8

million worse than the previous season’s loss of €20 million, despite making

steep cuts in personnel costs and player amortisation/impairment of €17

million.

This was largely due to two specific factors: (a) profit on

player sales was €19 million lower at just €5 million, which Aulas explained

thus, “we did not complete the plan to sell player registrations worth €20

million, because certain players changed their minds or were injured”; (b)

other expenses were €9 million higher, including a €6 million charge for the

exceptional “75% tax” on high salaries, which was voted in with retroactive

effect.

The damage was limited by a €3 million increase in revenue

to €104 million, largely as a result of more prize money from the Europa

League, partially offset by a reduction in commercial income and domestic TV

money.

This poor financial result was the worst in Ligue 1 in

2013/14. Although no fewer than 14 of the 20 clubs in France’s top flight

reported losses, Lyon’s €28 million was far ahead of the closest challengers:

Sochaux €18 million, Lille €16 million, Rennes €15 million and Marseille €13

million.

In fact, Lyon have the unenviable record of producing the

largest loss in Ligue 1 for each of the last five years (from 2010 onwards).

The chances are that Lyon will also make a reasonably large loss for the

2014/15 season, given that they reported a €9 million deficit for the first

half. Although they have continued to reduce wages and player amortisation,

revenue from the Europa League will be negligible, while there have been no

player sales of any note to compensate.

Lyon’s P&L statement over the last decade is like the

proverbial game of two halves: five years of solid profits between 2005 and

2009, as Lyon’s business model was the envy of most other clubs; then five

years of large losses between 2010 and 2014, as their expansionary approach

failed to deliver. That’s €110 million of profits, followed by €176 million of

losses, which is a big deterioration in anyone’s books. As Elvis Costello

nearly said, “Five years in reverse.”

Lyon’s profits were historically driven by profits on player

sales, as noted by the annual report: “The player trading policy forms an

integral part of the club’s ordinary business activities.” This usually

involved selling players to clubs “with significant purchasing power” such as

Real Madrid, Barcelona and Chelsea.

However, this all changed in 2010: in the preceding five

years Lyon generated €245 million of sales proceeds with a profit of €181

million, but this dipped to €103 million sales proceeds in the last five years

with a much reduced profit of €55 million.

The slowdown in trading activity can be attributed to a

number of factors with the club itself noting the impact of “the worldwide

recession and the implementation of UEFA’s Financial Fair Play (FFP) rules”,

but much of this is also down to Lyon taking their eye off the ball. They are a

long way from the boast made in 2007 that “revenue from player trading has

confirmed its recurrent nature over the long-term.”

Two transfers to London clubs illustrate the fact that Lyon

had rather lost its touch: in 2006 Aulas managed to negotiate an impressive €36

million from Chelsea for Michael Essien, but he secured less than €10 million

for Hugo Lloris from Tottenham seven years later.

The last mega money transfer was Karim Benzema to Real

Madrid for €35 million back in 2009, while Lyon have actually lost money on

some transfers, e.g. Abdul Kader Keita was purchased from Lille for €16.8

million, only to be sold to Galatasaray for half that amount, €8.4 million;

similarly Jean II Makoun was bought from Lille for €14.6 million, but sold to

Aston Villa for just €6.1 million.

Once the poster boy for successful player trading, Lyon are

clearly no longer one of the best in this activity. In fact, their profit from

player sales of €4.8 million was only the 10th highest in Ligue 1 in 2013/14,

even behind the likes of Evian and Lorient. While it might be fair to say that

economic conditions have reduced the chances of French clubs making big money

on player sales, that did not prevent four of them generating double-digit

profits: Lille €32 million, Paris Saint-German €23 million, Saint-Etienne €20

million and Toulouse €19 million.

Things look little better for Lyon in this area in 2014/15,

as noted by the report for the first nine months of the financial year:

“Proceeds from the sale of player registrations totaled €3.9 million, an

historic low, as the Board of Directors had decided to postpone the plan to

sell registrations last summer in favour of the season’s sporting performance.”

And that’s the point: it’s a tricky balance for Lyon to get their finances

right, while at the same time striving to do well on the pitch.

The other side of the coin is that Lyon have significantly

reduced player purchases, as shown by the sharp reduction in player

amortisation from €41 million in 2011 to just €15 million in 2014.

As a reminder, player amortisation represents the annual

cost of expensing player purchases. To clarify this point, transfer fees are

not fully expensed in the year a player is purchased, but the cost is

written-off evenly over the length of the player’s contract – even if the

entire fee is paid upfront. As an example, Yoann Gourcuff was bought from

Bordeaux for €22.4 million on a five-year deal, so the annual amortisation in

the accounts for him was €4.5 million.

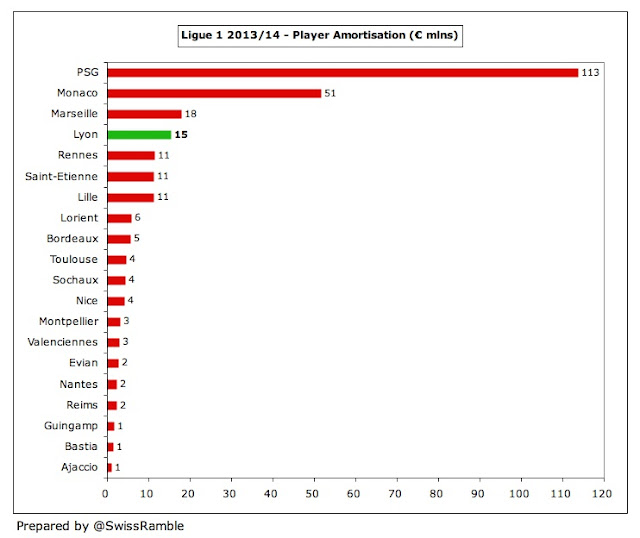

Lyon’s €15 million player amortisation was still the 4th

highest in Ligue 1 in 2013/14, but miles below PSG’s €113 million, which

highlights the fact that the Parisian club is at the other end of the spectrum

when it comes to buying players. In the same vein, Monaco’s player amortisation

was €51 million, while Marseille (perhaps a more reasonable comparison) were

also ahead of Lyon with €18 million.

However, not all of Lyon’s problems are due to player

trading, as the profitability of their core operations has also been declining.

This can be seen by looking at the club’s EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest,

Taxation, Depreciation and Amortisation), which can be considered a proxy for

the club’s profits excluding player trading, which has plummeted from €20

million in 2006 to minus €12 million in 2014. The trend is most certainly not

their friend in this case.

In fairness, very few French clubs achieve a positive

EBITDA, but Lyon’s is still one of the lowest. To put this into context,

Manchester United’s EBITDA of €182 million was nearly €200 million higher, which is a huge difference - every season.

Lyon’s revenue rose €3 million (3%) from €101 million to

€104 million in 2013/14, largely due to a €4.7 million (9%) increase in

broadcasting to €56 million with Europa League receipts up €6.2 million to

€13.3 million, while domestic TV money was down €4.7 million to €43 million.

Ticketing revenue was up €0.7 million (6%) to €13 million, but commercial

income was down €2.4 million (6%) to €35 million.

Despite the increase in 2014, revenue has fallen by a third

(€51 million) from the €156 million peak in 2008 with all revenue streams

decreasing: commercial by €24 million (40%), broadcasting €19 million (25%) and

match day €9 million (40%). Most of the decline in commercial income has come

from brand-related revenue, partly influenced by a series of once-off payments,

e.g. Sportfive paid €7 million a year from 2008 to 2011 after Lyon outsourced

its marketing rights to them. The decrease in broadcasting is very largely

because of lower prize money from European competitions.

Lyon’s revenue of €104 million is still the 4th highest in

France, behind PSG €474 million, Monaco €176 million and Marseille €132

million. PSG are miles ahead of all other French clubs, heavily boosted by their

commercial deal with the Qatar Tourism Authority. Lyon themselves are a long

way ahead of the clubs behind them, such as Lille €69 million, Bordeaux €67

million, Saint-Etienne €53 million and Rennes €43 million.

The Deloitte Money League is a useful barometer for Lyon’s

revenue decline, as they were as high as 11th in 2006 and 12th in 2008, but are

not even in the top 30 clubs in the latest edition, which features only two

French clubs: PSG and Marseille (note: for some reason Monaco are not included even

though their revenue per the DNCG

Comptes Individuels des Clubs would place them in the top 15).

While Lyon’s revenue has decreased by €51 million since

2008, the leading European clubs have all seen their revenue grow by nearly

€200 million in the same period: Bayern Munich €193 million, Manchester United

€193 million, Real Madrid €184 million and Barcelona €176 million. French clubs

will continue to struggle, especially compared to English clubs, as their TV

deal continues to lag their colleagues across the Channel.

Nevertheless broadcasting accounted for 54% of Lyon’s

revenue in 2013/14, up from 51% the previous season, with commercial income’s

share falling from 37% to 34%. Match day remained unchanged at 12%.

Lyon’s domestic TV revenue was €1.5 million (3%) lower in

2013/14 at €43 million, including €41 million from Ligue 1. The distribution

model for French TV money is relatively equitable with 50% allocated as an

equal share, while the remainder is distributed based on league performance 30%

(25% for the current season, 5% for the last five seasons) and the number of

times a team is broadcast 20% (over the last five seasons). Lyon were only

surpassed by PSG €45 million (due to them winning the league) and Marseille €42

million (more games shown live).

The Ligue 1 TV deal is actually 5% lower at €637 million

from the 2014/15 season (the second half of the four-year agreement),

comprising €604 million for domestic rights and just €33 million for

international rights. A new four-year deal with Canal+ and BeIN Sports will

increase domestic rights from the 2016/17 season by 24% to €748.5 million,

while the international rights will rise 142% to €80 million in a new six-year

deal with BeIN Sports from the 2018/19 season. That will take the total TV deal

to €829 million, but this pales into insignificance compared to the new Premier

League deal, which is estimated to be worth €3.8 billion a season from 2016/17.

The other element of broadcasting revenue is prize money

from UEFA competitions, which rose €6 million from €7 million to €13 million in

2013/14, thanks to Lyon reaching the quarter-finals compared to the last 32 the

previous season. In fact, thanks to a large TV pool payment, Lyon’s €10.2

million in prize money was the second highest received in the Europa League,

only behind Sevilla’s €14.6 million. The €13.3 million booked in Lyon’s

accounts also included €2.1 million for the Champions League play-off match and

£0.9 million additional payment from the 2012/13 competition.

That’s not too bad, but it is a lot lower than the money

clubs received in the Champions League, e.g. Marseille earned €32 million even

though they lost all six of their group games. Lyon’s best performance in the

Champions League came in 2010 when they reached the semi-final, which was worth

€29 million in prize money. However, they have missed out on recent

improvements in the TV and marketing rights, as can be seen by PSG receiving an

impressive €54 million for reaching the quarter-final in 2013/14.

Unfortunately the 2014/15 accounts will include minimal

revenue from Europe (€2 million in the first nine months’ accounts), as Lyon

lost in the Europa League play-off.

"Take it to the Max"

After Lyon’s profits from player sales dried up, the loss of

revenue from the lucrative Champions League was the final nail in the coffin.

In 2012/13 the club estimated that the absence from Europe’s premier

competition had cost them around €20 million, including gate receipts and the

impact on commercial deals. Little wonder that the annual report stated, “Our

on-the-pitch objective is to return as quickly as possible to the Champions

League.”

The fact is that Lyon desperately need to play in the

Champions League to generate more revenue, so the qualification for the 2015/16

tournament is massively important, especially as the new TV deal will increase

revenue by more than 30% from next season.

Lyon’s gate receipts rose 6% (€0.7 million) to €13 million

in 2013/14, due to the greater number of home games. This was the 3rd highest

in Ligue 1, only behind PSG €39 million and Marseille €14 million and just

ahead of Lille €11 million. All the other clubs earn less than €10 million a

season. The last time that Lyon were in the Deloitte Money League in 2011/12

they had the second lowest match day revenue of the top 20 European clubs.

Their average attendance of 34,414 was 7% higher than the

previous season’s 32,084 with the club announcing that the number of spectators

at the Gerland stadium reached an all-time high in 2013/14 with more than 1

million attending.

The lack of match day revenue has inspired the club to build

a new stadium at the Olympique Lyonnais Park. Aulas has emphasised the

importance of this project: “The new stadium, once built, will enable the club

to cross an important threshold. Like all the other major European clubs, we

have decided to be owners of our new stadium, so that (we) can earn all of the

revenue generated by the Park and enjoy advantages comparable to those of our

major European competitors.”

The club recently quantified these advantages, stating that

the new stadium “should generate additional revenues of around €70 million per

annum within the next five years”, including naming rights where “discussions

are underway with several large French and international companies.”

Work began in July 2013 and the stadium should be

operational from early 2016, i.e. from the second half of the 2015/16 season.

It will have 58,000 seats, including 6,000 VIP seats, of which 1,500 will be in

106 private boxes. There will be a training centre with 5 pitches and a

dedicated sports medicine facility. Revenue generation will be helped by two

hotels, restaurants, offices and an entertainment complex, while the stadium

can hold up to 10 events (concerts, shows, etc) a year. It will stage six

matches in Euro 2016, including a quarter-final and semi-final.

The total cost is €405 million and will be financed by a

mixture of: equity €135 million, bond issues €112 million, bank borrowing

€144.5 million; and €13.5 million guaranteed revenue/naming rights.

Commercial income fell 6% (€2.4 million) to €35 million in

2013/14. This comprises sponsoring and advertising, down 9% (€2 million) to €19

million, and brand-related revenue, down 3% (€0.5 million) to €16 million.

Sponsorship revenue was actually stable, excluding a €2

million once-off fee in 2012/13 related to the new stadium project. Lyon’s €19

million was the 4th highest in Ligue 1, only surpassed by Monaco €140 million,

PSG €79 million and Marseille €24 million. Lyon’s main shirt sponsor is

Hyundai, whose deal was extended two seasons until the end of 2015/16 for all

Ligue 1 matches, while Veolia have an agreement for European and domestic cup

matches until June 2016.

Lyon have a 10-year kit supplier deal with Adidas, running

until June 2020. According to the club, the contract is “worth between €80-100

million”, depending on sports results in French and European competitions. Lyon

lists numerous sponsors in its accounts, but it is worth noting the deal with

Sportfive, who were granted certain exclusive marketing rights for a minimum of

10 years from 2012 relating to events organised at the new stadium in return

for a €28 million signing fee (paid in four annual instalments of €7 million).

Lyon’s commercial income has frequently been influenced by

once-off signing fees, such as €3.5 million paid by Sodexo in 2007/08, while

the 2014/15 results will be boosted by a €3 million fee related to catering for

the new stadium.

Lyon’s brand-related revenue of €16 million was almost

identical to Marseille, but was dwarfed by PSG’s €270 million, which included

the enormous deal with the Qatari Tourist Authority.

The wage bill was cut by 9% (€7.6 million) from €82.4

million to €74.8 million, reducing the wages to turnover ratio from 81% to 72%.

This continued Lyon’s trend of lowering the wage bill, which has fallen by

around a third (€37 million) from the peak of €112 million in 2010 (though the

figures up to that year included around €20 million for image rights payments).

The wages decrease is in line with the revenue reduction over the same period.

Aulas had criticised the “pharaohs and dinosaurs” who had

been awarded bumper contracts when the going was good, but then failed to

deliver on the pitch. After Lyon missed out on Champions League qualification,

the chairman warned that the club would have to make “economic adjustments” and

he wasn’t kidding.

Despite the improvement in the wages to turnover ratio,

Lyon’s 72% is still above UEFA’s guideline of an upper limit of 70%, but it is

by no means the worst in Ligue 1. Six clubs have ratios above 80%, the highest

being Rennes 97% and Lille 90%.

Just like revenue, Lyon have the 4th highest wage bill in

Ligue 1 with €75 million. Obviously, PSG are out of sight with €240 million,

but Lyon are also a fair way behind Monaco €95 million and Marseille €85

million.

Lyon’s principal method of reducing the wage bill and indeed

the amortisation of player registrations is to “capitalize on the potential of

young players coming out of the OL Academy” rather than buy stars whose

acquisition cost and salary would be significantly greater. They have well and

truly learnt their lesson here.

Not only is the Academy “central to the club’s strategy”,

but it is a source of much pride, as it is largely based on Lyon’s “local

identity”. As Aulas says, this creates players who have “strong bonds with the

club and are proud to wear the shirt”, adding, “it also generates enthusiasm

among fans, who share these values.”

The excellence of Lyon’s academy, recognised as the best in

France and one of the finest internationally, has not come about by chance, as

the club has devoted more than €7 million a year to this area, described as

“part of the club’s DNA”. Lyon have the advantage of being able to promise

young players that they will be given an early chance to break into the first

team. Indeed, in the 2013/14 season an incredible 22 of the 33 professional players

were graduates of the Academy and eight or nine of the starting players in

every match were trained at OL. The average age of the squad was a youthful 24.

Lyon’s focus on homegrown players can be seen by the

dramatic reduction in player purchases after the 2010/11 season. In the six

seasons up to that point Lyon’s average spend per season was €53 million, but

this fell to just €8 million in the three seasons since, including a tiny €2.6

million in 2013/14.

This meant that Lyon moved from average net spend of €10

million to net sales of €15 million in these periods, even though sales

proceeds themselves fell from €43 million to €22 million.

The lack of big money buys from other clubs has impacted the

balance sheet with the value of player (intangible) assets decreasing from €122

million in 2010 to just €13 million today. However, the value in the books is

much lower than the value that could be realised in the market if players were

sold, especially as homegrown players have zero value on the balance sheet. In

the 2014/15 half-year accounts (with the help of Transfermarkt),

Lyon estimated that this unrealised profit was as much as €111 million, up from

€79 million in 2013/14.

Around 90% of this potential capital gain relates to players

who come from the Academy, which “proves that our strategy makes sense”. So,

Lyon’s focus on youth has not only been a financial necessity, but will likely

mark a return to the business model on which it built its success, namely

profitable player sales.

The jewels in the crown are exciting forward Alexandre

Lacazette, who Aulas said was worth more than €50 million, and tricky winger

Nabil Fekir, who the chairman has compared to Messi. That might be considered

to be promotional sales talk, but both players have now broken into the French

national team. Other good prospects include the elegant midfielder Clément

Grenier, the dynamic captain Maxime Gonalons and the progressive full-back

Samuel Umtiti.

Lyon’s debt has obviously been greatly influenced by the

borrowing for the new stadium, which is now up to €112 million after the final

€10 million tranche was issued in June 2015, split between the VINCI Group €80

million and Caisse des

Dépôts et Consignations €32 million. The stadium debt was €48

million in the 2013/14 accounts, but had increased to €102 million in the

2014/15 half-year accounts.

In 2013/14 other financial liabilities were €33 million,

largely OCEANE bonds of €23 million and bank credit facilities of €4 million,

but had risen to €56 million in the half-year accounts. In June 2014 the OL

Group signed a €34 million line of credit to secure its medium-term financing

needs.

Before the financing for the new stadium was required, Lyon

were in the happy position of having net funds instead of debt. In fact, the

club said that its “financial structure was one of the most sound in Ligue 1.”

However, that has obviously changed in the last couple of years.

Much like Arsenal, who had to finance the construction of

the Emirates Stadium, the impact has been felt on the playing side, with net

player debt moving to net player receivables.

Lyon’s cash flow from operating activities has been consistently

negative for many years. As we have seen, there has been minimal investment in

the playing squad, but substantial investment in infrastructure, including €100

million on the new stadium including €74 million in 2013/14 alone.

The club’s investment has been largely financed by new bonds

or increases in share capital, which contributed €138 million and €91 million

respectively in the last eight years, while other loans have been repaid. The

bonds issued in 2010/11 were “mainly for financing the acquisition of player

registrations”, while the bonds issued recently have been to fund the new

stadium.

Since the 2013/14 accounts closed, further funding has been

raised: €51 million of bonds in September 2014, €10 million of bonds in June

2015 and a €53 million increase in share capital in June 2015.

The accounts state that the average annual financing rate on

the new stadium bank and bond financing (which is estimated at €248.5 million)

will be around 7% from the time the stadium begins operating, so that will

represent a sizeable interest burden each year.

"Kick Up Ya Foot"

An important driver of Lyon’s new, cost conscious model has

been the advent of Financial Fair Play, as explained in the 2013 annual report:

“The strategy in place for more than two years now aims to return OL Group to

structural operating break-even by the end of the 2013/14 season. These

objectives comply with UEFA’s FFP.”

Even though Lyon obviously did not meet their 2013/14

break-even objective, the club confirmed in April that “no further action would

be taken” following a UEFA investigation of additional information requested

following the large reported losses. Presumably Lyon must have been saved by

the various allowable deductions in UEFA’s break-even calculation, including

“healthy” costs such as those incurred for the academy and stadium development

plus the cost of players under contract before June 2010.

Given Lyon’s losses, it is perhaps no surprise that Aulas

has been a vocal supporter of PSG’s push to get UEFA to amend the FFP regulations,

though he makes a good point about the differences between countries: “It's not

the problem of Paris Saint-Germain. It's the problem of the difference between

financial fair play and the constraints of each of the clubs. There is a

European rule, and other rules in each of the countries, so there has to be a

move towards harmonisation.” As an example, local tax rules mean that it is far

more expensive to employ a player in France than any other major European

league.

"Jordan: The Comeback"

It is too early to say that Lyon are back, especially given

the huge financial advantages enjoyed by PSG in France, but it is easy to get

behind their new business model, based on players developed at the OL Academy.

The club has already taken its first steps towards recovery by shining in Ligue

1 last season and so returning to the Champions League, which is crucial for

Lyon to fully exploit the opportunities that its wonderful new stadium will

provide.

Of course, the emergence of young talent can be a

double-edged sword, as their success makes it more likely that wealthier clubs

will tempt them away, but at least that would be true to Lyon’s previous

successful business model. It is not difficult to imagine a wily old fox like

Jean-Michel Aulas having the last laugh, but in the meantime let’s just enjoy

the young guns going for it.

Quality and informative read, gives a great insight onto Lyon's past, present and future financial plans/results.

ReplyDeleteI am very excited by President Aulas and his prospective plans.

We expect more "rambling" about Lyon in the near future, this after they roar in Ligue 1, and hopefully Champions League.

This was a fantastic read. You have a great niche here providing the finance of sporting teams. Keep up the great work, I'm adding this to my RSS feed.

ReplyDeleteSuch a fantastic and informative post-and website.

ReplyDeleteExcellent work, the figures are very clear and detailed, analysis is spot on. Congrats !

ReplyDeleteThe first semester 2015 (01/07-31/12/2014) shows that revenues are still low due to very few player trading and no presence in european competitions but shows also a steady decrease in players amortisation and acquisition.

With the return of Champions league and the new stadium almost ready the future seems a bit brighter for OL.

However, young players from the academy start to attract interest from richer clubs and negotiate much higher salaries to stay at the club...