As West Bromwich Albion prepare for their sixth consecutive

season in the Premier League, it’s fair to say that they have managed to have

rid themselves of the unwanted tag of being a “yo-yo” club that constantly bounces

between the Championship and the top flight.

However, the fight to retain their Premier League status has

not been without problems in the last two years. They narrowly avoided

relegation in 2013/14 when they finished in 17th place, while Albion looked in

some danger last season before the Tony Pulis effect kicked in with the results

under the experienced manager enough to guide the team to mid-table security.

Chairman Jeremy Peace said that this was “testament to the relentless intensity

that (Pulis) brings to the challenge” and the team’s improvement fully

justified his decision to bring in the Welshman in January.

This coaching change was nothing new for West Brom, who have

got through a fair number of managers in their determination to stay in the lucrative

Premier League. Since Roy Hodgson left West Brom for the England job three

years ago, they have employed no fewer than five managers. First up was Steve

Clarke, who guided the club to its highest ever Premier League position of 8th

in 2012/13, before a lengthy run of poor results ended in his sacking.

He was replaced by Keith Downing, temporarily elevated from

his coaching role, before the former Betis coach Pepe Mel took charge until the

end of the 2013/14 season. It was then the turn of Alan Irvine, who was shown

the door after a worrying run of only four wins in 19 league games left the

club perilously close to the relegation zone, only for Pulis to come in and

work his particular brand of magic.

"All the things he Saido"

Throughout this period of managerial upheaval, West Brom

have maintained their “steady as she goes” approach, refusing to gamble on the

club’s future, resulting in a financial record that is the envy of many. As

Peace explained, “We strive to deliver Premier League football whilst growing

the club within our means.”

This conservative approach was echoed by chief executive

Mark Jenkins, “The club has continued to invest in its playing squad, both in

transfer fees and wages. However, with careful budgeting and tight financial

controls, we have managed to match our revenue to our costs.” Granted, this

might not be the most thrilling of manifestos, but it has clearly worked to

date.

While some fans would clearly like the club to spend more on

players, that is no guarantee of success. Indeed, they only have to look at

Birmingham City, another West Midlands club, to underline this fact, as the

Blues were overly reckless and ended up in deep trouble.

In contrast, West Brom have been a model of stability with

Peace describing them as “a sound company – an extremely solid football club

with no debt, significant assets, a developing infrastructure and reasons to be

confident about the future.” That’s a pretty strong sales pitch, which is

possibly no coincidence, as the club has effectively been in the shop window

for the last few months.

"James Morrison - light my fire"

Peace admitted that the board was “considering strategic

options for the future development and legacy of the club”, leading to a number

of potential investors from China, America and the Far East expressing interest

in acquiring West Brom. This month the chairman confirmed that exclusivity had

been granted to one interested party.

The purchase price is believed to be around £150 million,

which might sound a little steep for a mid-table club, but it is obviously

linked to the riches available to those competing in the Premier League from

the new broadcasting deal. This would represent a significant gain for Peace,

who holds an 88% share of the club through his company West Bromwich Albion

Holdings Limited, and has been in charge at The Hawthorns since 2002.

Although the prospective buyers are now conducting due

diligence, Peace says that he does not want this to be a long-running saga that

might become a major distraction to the club’s preparations for next season. If

a deal cannot be concluded early in the summer, then any takeover would be put

on hold for at least another season.

One of the main reasons that West Brom might be attractive

to an investor is its strong financial record. Unlike many football clubs, they

have been consistently profitable and have virtually no debt. The latest

published accounts from the 2013/14 season once again confirmed their ability

to make money, as profit before tax more than doubled from £6.0 million to

£12.8 million (£10.8 million after tax).

The near £7 million improvement in profit was largely due to

the £17 million (24%) revenue growth to a record £87 million, almost entirely

from the new Premier League three-year TV deal that started in the 2013/14

season. However, this was offset by higher costs with wages surging £11 million

(21%) to £65 million, player amortisation up £2 million (80%) and other

expenses rising £3 million (33%).

The figures were then boosted by a £7 million increase in

the profit made from player sales to £10 million, mainly from the transfers of

Shane Long to Hull City and Peter Odemwingie to Cardiff City.

In most years West Brom’s £12.8 million would have been one

of the highest profits in the Premier League, but the times they are a-changing

in England’s top flight, as a combination of higher TV money and the financial

fair play rules that restrict wage growth meant that no fewer than 15 clubs

reported profits in 2013/14.

West Brom had the 8th highest profit in the Premier League,

which is still to be commended, especially as the profits of five of the seven

clubs above them were significantly influenced by player sales. While West

Brom’s £10 million from this activity was not too shabby, it was still lower

than Tottenham £104 million, Chelsea £65 million, Southampton £32 million,

Everton £28 million and Newcastle United £14 million.

Most of these profits came from one major sale, e.g. Gareth

Bale from Tottenham to Real Madrid, David Luiz from Chelsea to Paris

Saint-Germain, Adam Lallana to Liverpool and Marouane Fellaini from Everton to

Manchester United, but West Brom’s profits come from a more predictable model.

Variety may be the spice of life, but consistency pays the

bills, as can be seen by West Brom’s admirable performance off the pitch, where

they have reported profits in eight of the last 10 years. This is a great

achievement, especially as three of those years were spent in the Championship,

where almost all teams lose money as they strive to reach the Premier League.

West Brom’s aggregate profit of £38 million over the last

four seasons is actually the 5th highest in the Premier League and about the

same as mighty Manchester United £39 million. This is only surpassed by

Tottenham £77 million, Arsenal £63 million and Newcastle United £63 million.

In terms of consistency, West Brom are one of only three

clubs that have reported profits in each of those four seasons, which is a

seriously impressive accomplishment in the highly competitive Premier League.

The only other clubs to achieve this feat are Arsenal, the poster child for

financial responsibility, and Newcastle United, largely thanks to Mike Ashley’s

lack of investment.

In fact, the only occasions that West Brom have recorded a

loss in the past decade, 2006 and 2009, were driven by aggressive use of impairment

accounting for player values, which increased costs by £9.4 million in 2006 and

£17.8 million in 2009. If these items were excluded, West Brom would have also

reported profits in both of those years.

On the other hand, their results have been helped in other

years by booking reversals on past impairment losses on player registrations,

notably £3.0 million in 2007. Similarly, the large £18.9 million profit in 2011

was boosted by the waiver of £7.6 million of inter-company debt with West

Bromwich Albion Heritage Limited as part of the group reorganisation.

To better understand the reasons for the player impairment,

we need to explore how football clubs account for player purchases.

Importantly, transfer fees are not fully expensed in the year a player is

purchased. Instead, the cost is written-off evenly over the length of the

player’s contract via player amortisation – even if the entire fee is paid

upfront.

As an example, if a player was bought from for £10 million

on a four-year deal, the annual amortisation in the accounts for him would be

£2.5 million. After two years, the cumulative amortisation would be £5 million,

leaving a value of £5 million in the accounts. However, if the directors were

to assess the player’s achievable sales value as £3 million, then they would

book an impairment charge of £2 million. Impairment could thus be considered as

accelerated player amortisation.

As we have seen, while West Brom may be considered a selling

club, they do not really make big money from this activity, though it is

undoubtedly a useful revenue stream. The only double digit profit from player

sales in the past few years was the £18 million received in 2008, mainly for

the transfers of Diomansy Kamara, Jason Koumas and Nathan Ellington.

Player amortisation has been falling from the £17 million

peak in 2006, though this has obviously been impacted by the impairment

provisions. Although it rebounded to £5 million in 2014, this is still the

lowest in the Premier League.

The only other clubs with annual amortisation below £10

million were Crystal Palace £5.7 million and Hull City £9.9 million, while this

is a far more important expense at the big spenders, e.g. Manchester City £76

million, Chelsea £72 million and Manchester United £55 million. This is a reflection

of West Brom’s limited spending in the transfer market, though it is likely to

have increased in the 2014/15 accounts following the acquisition of the

relatively expensive Brown Ideye and Callum McManaman.

With player trading not playing that big a part in West

Brom’s model, their profits have largely been down to their underlying

business, which can be seen by looking at the club’s EBITDA (Earnings Before

Interest, Taxation, Depreciation and Amortisation). Apart from a couple of

blips, this has been positive year after year in a steady range of £5-10

million.

That said, although EBITDA improved by £2 million in 2014,

West Brom’s £9 million was still the second lowest in the Premier League, only

ahead of Fulham £2 million. In fairness, few people would expect them to

compete with elite clubs such as Manchester United £130 million and Manchester

City £75 million, but this is still a long way below the likes of Norwich City

£33 million, Crystal Palace £30 million and Southampton £28 million. This highlights

how well West Brom have done in balancing the books when their core business

generates so little cash (relatively speaking).

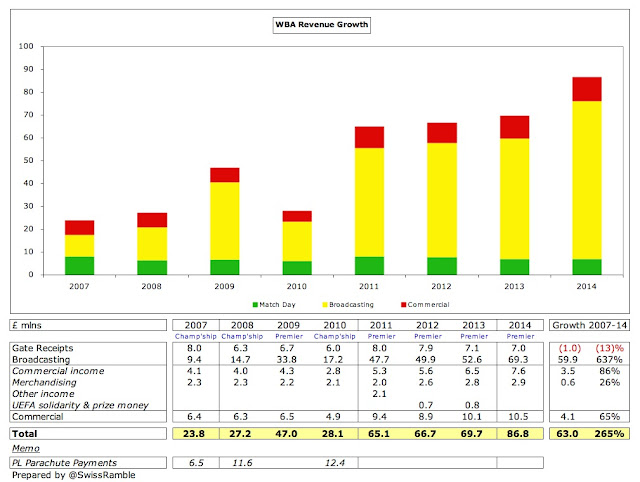

Revenue rose 24% (£17.1 million) from £69.7 million to £86.8

million in 2013/14, almost entirely due to broadcasting, which rocketed 32%

(£16.7 million) from £52.6 million to £69.3 million on the back of the new

Premier League deal. Commercial income also rose 5% (£0.5 million) to £10.5

million, but gate receipts fell 2% (£0.1 million) to £7.0 million.

In fact, almost all of West Brom’s revenue growth over the

last few years is attributable to centrally negotiated rises in the Premier

League TV deal. Revenue has increased by an impressive £63 million since 2007,

but £60 million of this is from TV money. Commercial income has also risen £4

million, but gate receipts are actually £1 million lower in this period.

Clearly, revenue was much lower in the Championship on

account of the far smaller TV deals in the Football League, though this was

somewhat cushioned by parachute payments in West Brom’s case. In addition,

commercial revenue and gate receipts are also reduced in the second tier.

Despite the healthy growth, West Brom’s revenue is still

only the 18th highest in the Premier League, ahead of Hull City £84 million and

Cardiff City £83 million. To place this into context, Manchester United’s £433

million is almost exactly five times as much, while there are four other clubs

earning more than £250 million: Manchester City £347 million, Chelsea £320

million, Arsenal £299 million and Liverpool £256 million.

Even though every Premier League club is now in the top 40

in the Deloitte Money League, thanks to the amazing TV deal, this does not help

domestically when the disparity is so enormous. As Pearce put it, “Every season

it is getting tougher competing in the Premier League. You’ve got the huge

clubs and the rest of us.”

Unsurprisingly West Brom’s business is dominated by

broadcasting, which now contributes 80% of their total revenue, up from 76% the

previous season. Commercial is down to 12%, while match day has fallen to just

8%.

Incredibly three Premier League clubs had an even higher

reliance on TV money than West Brom with Crystal Palace and Swansea City both

earning around 82% of their revenue from broadcasting. Given the importance of

the TV money, it is little wonder that Pulis was recruited with his record of

never being relegated in his 22 years of management.

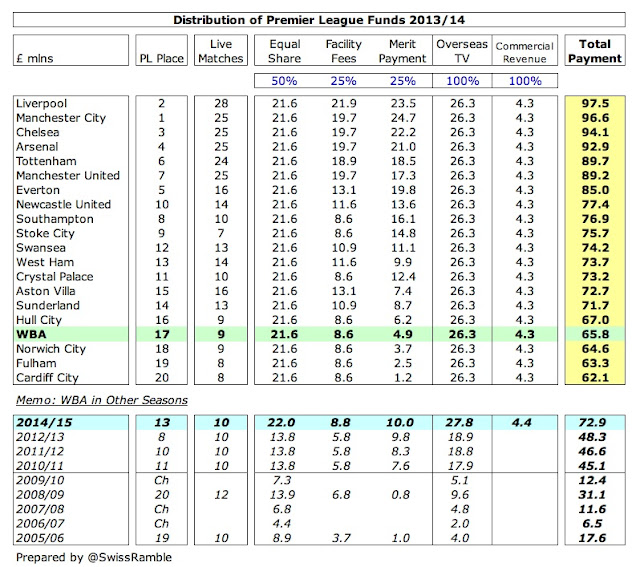

Considering the significance of Premier League television

money to West Brom, it is worth exploring how this is distributed in some

detail. In 2013/14 West Brom’s share rose 36% (£17.5 million) from £48.3

million to £65.8 million. This is based on a fairly equitable distribution

methodology with the top club (Liverpool) receiving around £98 million, while

the bottom club (Cardiff City) got £62 million.

Most of the money is allocated equally to each club, which

means 50% of the domestic rights (£21.6 million in 2013/14), 100% of the

overseas rights (£26.3 million) and 100% of the commercial revenue (£4.3

million). However, merit payments (25% of domestic rights) are worth £1.2

million per place in the league table and facility fees (25% of domestic

rights) depend on how many times each club is broadcast live.

In this way, West Brom falling from 8th to 17th in the league

directly cost them £11.2 million, as their merit payment was only worth £4.9

million, compared to the £16.1 million that 8th placed Southampton received.

Thus, the improvement to 13th place in the 2014/15 season will boost West

Brom’s Premier League money to £72.9 million, an increase of £7.1 million.

What is also clear is that West Brom’s distributions have

been restricted by being broadcast live no more than 10 times, which is the

contractual minimum, receiving £8.6 million, compared to, say, Aston Villa’s

£13.1 million for being shown live 16 times. This is a hidden way in which the

more “glamorous” clubs receive more money.

Of course, there will be even more money available when the

next three-year cycle starts in 2016/17 with the recently signed extraordinary

UK deals with Sky and BT producing a further 70% uplift. My estimate is that a

club that finishes 13th in the distribution table (as West Brom did in 2014/15)

would receive around £111 million a season, which would represent an additional

£38 million, compared to the current £73 million.

West Brom’s match day revenue of £7 million is the lowest in

the Premier League, though four other clubs are also below £10 million: Stoke

City £7.7 million, Cardiff City £8.3 million, Swansea City £9.2 million and

Crystal Palace £9.3 million. Although not great from the perspective of the

bottom line, West Brom have done the decent thing by applying big price

reductions in 2012/13 season by a freeze on prices for the next two seasons.

However, as Echo & The Bunnymen once said, nothing lasts

forever and the club has recently announced that tickets will rise by up to 14%

for the 2015/16 season, though Peace noted that “we remain one of the lowest

priced clubs in the top two divisions”, adding that “adult prices for next

season will still be 10% lower than a decade ago.” The justification for the

increase was competitive pressure: “It is not something the club would have

introduced had we not felt it necessary in the quest for West Bromwich Albion

to remain as competitive as possible in a league which is relentless in its

advances.”

Despite the ticket price reduction and subsequent freeze,

attendances have remained fairly flat at around the 25,000 level, albeit higher

than the crowds in the Championship. The average of 25,194 in the 2013/14

season was the 16th highest in the Premier League, slightly higher than Fulham.

There had been plans to increase the capacity of The

Hawthorns from around 27,000 to 33,000 by redeveloping the West Stand, but

these have since been shelved following the lack of improvement in attendances,

which Pearce ascribes to the poor economic environment and the increasing

number of televised games. Instead, Pearce said, “we will now find ways of

adding seats within the existing stadium rather than building new capacity and

creating indebtedness within the football club.”

Commercial revenue rose 5% (£0.5 million) to £10.5 million

in 2013/14, despite the absence of £0.8 million solidarity money from UEFA that

was booked the previous season. Commercial income was up 17% (£1.1 million) to

£7.6 million, while merchandising was slightly higher at £2.9 million.

Although this is the fifth lowest in the Premier League,

that’s a pretty good performance, only just behind Premier League stalwarts

Everton £12.7 million and Fulham £12.3 million. As might be expected, clubs

like Manchester United £189 million and Manchester City £166 million are out of

sight, but that’s not really a valid comparison.

Similarly, West Brom’s shirt sponsorship is one of the smallest

in the top flight. In 2013/14 the shirts sponsor was Zoopla, but they ended

their £1.5 million deal at the end of that season, partly in response to the

actions of former striker Nicolas Anelka who is alleged to have made a gesture

known as the quenelle,

which many consider to have anti-Semitic connotations.

As a result, West Brom had to rapidly find a new sponsor

with Intuit Quick Books stepping in, albeit at a reduced rate of £1.2 million

for the 2014/15 season. Recently the club has announced that their sponsor for

the 2015/16 season will be TLC Bet, an Asian betting company, with a better

deal approaching £2 million.

No such problems with the kit supplier, as Adidas have

recently extended the deal originally signed in 2011/12 to the end of the 2015/16

season, though some supporters were unhappy with last season’s white, pinstripe

kit. Even though Pearce claimed that this was West Brom’s best-selling shirt,

they will return to the traditional dark blue-and-white stripes next season.

The wage bill shot up 21% (£11.5 million) from £54.0 million

to £65.5 million, though the wages to turnover ratio actually improved from 77%

to 75% in line with the high revenue growth. Understandably, the wage bill has

fluctuated depending on whether West Brom are in the Championship or the

Premier League, but wages have been steadily increasing since promotion in

2010, rising by 190% since then. This is pretty much in line with the revenue

growth of 209% in the same period, a clear sign of the Board’s desire to “control

costs in a prudent manner.”

This sensible approach includes a large performance-related

element, as Pearce explained: “You have some appearance money. We have a

retention of status bonus if we stay up. They get a certain amount per point.

We have flex-downs (up to 50%), so if we get relegated, we have the downside

covered on the commitment on the wages.”

Indeed, Albion are one of the few clubs that mention the

future wage liability for the remainder of player contracts in their accounts,

though it should be noted that this had increased to £94 million following the

purchase of players after the end of the 2013/14 season.

Nevertheless, it is still a real challenge for a club of

West Brom’s size to pay enough wages to be competitive, as chief executive Mark

Jenkins explained, “Of all the Premier League clubs, we commit the highest

percentage of our revenue to salaries, the bulk of which is to fund a squad to

challenge at the top level.” He is absolutely correct, as West Brom’s wages to

turnover ratio of 75% is the highest (worst) in the top tier with only Fulham

approaching the same level in 2013/14.

This is not because of an outlandish wage bill, as West

Brom’s £65 million is the 12th highest in the Premier League, but that becomes

a problem when it is out of line with the revenue, which is only 17th highest.

The temptation to spend more on wages is perfectly understandable, given the

close correlation with success on the pitch, especially as so many clubs spend

between £60-70 million.

In fact, there has been a clear convergence of clubs in this

range, as the traditional bigger spenders like West Ham and Aston Villa have

only grown a little, while the nouveaux

riches like Stoke City, Swansea City, Southampton and indeed West

Brom have all had to significantly increase their wage bill in order to

compete. The Baggies are likely to further increase their wages in 2014/15

after bringing more players in and paying higher bonuses for the better league

finish.

One point worthy of attention is the £1.022 million

remuneration given to the highest paid director, who is not named, but

presumably is Peace. Although this is lower than the previous season’s £1.341

million, it is still a tidy sum for a business of this size.

West Brom have rarely been big spenders in the transfer

market, which has been a source of frustration to some fans, though the brief

has been “to ensure our limited resources are invested wisely.” However, this

prudent approach has changed recently with a significant increase in spending

in the last two seasons. The average annual gross spend has doubled from £8

million between 2006 and 2013 to £16 million between 2013 and 2015, while net

spend has risen from a paltry £2 million to £10 million in the same period.

However, everything is relative, Even after this increase,

West Brom are no higher than mid-table in terms of net spend in the Premier

League, still behind the likes of Crystal Palace, West Ham, Hull City and Aston

Villa, as well as the usual suspects (United, City, Arsenal, Chelsea and Liverpool).

As a natural consequence of Albion’s parsimonious approach,

their net debt is very low at just £2.1 million, which comprise a bank

overdraft secured on the club’s assets of £3.6 million less cash balances of

£1.5 million. Following promotion in 2010, debt has been cut from £10 million.

The balance sheet also includes £2.1 million owed to group

undertakings, but this is more than covered by £8.5 million owed by group

undertakings. In addition, there are contingent liabilities of £2.4 million in

respect of player purchases, which are dependent on things like the number of

appearances that a player makes.

The reality is that West Brom are effectively debt-free,

which is a magnificent achievement for a club of their resources operating in

the Premier League, as can be seen by the amount of debt other clubs of their

level have built up, e.g. Cardiff City £135 million and Hull City £67 million.

It is therefore no great surprise that they appear to have loosened the purse

strings a little, especially with the blockbuster Premier League deal on the

horizon.

Basically, West Brom operate a self-sustaining model that

does not require additional loans or increases in share capital, so you might

expect them to be firm proponents of Financial Fair Play (FFP), which

essentially forces clubs to live within their means.

However, that is not the case, as Peace explained: “We were

not in favour of the introduction of these regulations. Whilst it is our view

that all football clubs should be financed in a sustainable manner that is

guaranteed, we would prefer to operate in a market free from other regulations.

We regard Financial Fair Play as a misnomer. We believe the new rules are

anti-competitive and will further reinforce the existing pecking order in the

Premier League. No longer will a major investor be able to join a club and

change the Premier League landscape.” He added, “The new FFP rules mean that we

will, more than ever, have to think outside the box to ensure our limited

resources go further.”

"Hong Kong Gardner"

This might mean an increasing focus on youth to produce

talent such as the exciting forward Saido Berahino. According to Peace, the

club invests £3 million a year in their Academy (net £2.2 million after a

subsidy of £800,000) and has been awarded Category One status. New facilities

were unveiled in January by Baggies legend Tony ‘Bomber’ Brown.

Then again, this brings its own challenges with Berahino

openly talking about hoping to “move on to bigger things.” In much the same

way, Albion lost the talented Izzy Brown to Chelsea for nominal compensation,

due to the much criticised Elite Player Performance Plan. Even so, there is

still optimism about some of the youngsters at the Academy, such as forwards

Adil Nabi and Jonathan Leko.

Peace is the first to admit that West Brom have had “a

couple of difficult seasons during which we have not made the progress we

wanted”, but things have markedly improved since the arrival of Tony Pulis and

he will have the whole summer to “address the playing squad more fully and

re-shape it into something more akin to his specifications.”

"Is Vic there?"

A change in ownership is something that could complicate

this objective, but Peace has said that any new management would commit to “the

management model which I believe has served the club so well.” He promised that

any transition to new owners “should be smooth and devoid of upheaval.”

Let us hope that he is correct, as there is much to admire

in West Brom’s under-stated approach, As Peace said, “We are plugging away,

trying to compete in the most high-profile, difficult league in the world,

punching way above our weight.” The club deserves a lot of credit for that,

while at the same time remaining profitable and debt-free.

A takeover could provide additional impetus to West Brom,

though Financial Fair Play regulations mean that a new owner could not operate

with complete freedom. In any case, it might be worth remembering the old

saying, “the grass isn’t always greener on the other side.”

Not a bad assessment.

ReplyDeleteYou have fallen into the "profits trap" however". As you have highlighted, the losses are due to impairments on players contracts upon relegation.

For your assessment to be complete, you should demonstrate a cashflow analysis over the last 10 years. This will show you why WBA has no debt, rather than concentrate on Profit. You can spend cash - you can't spend profit.

7/10

If you read any of my other pieces, you will see that I invariably comment on the cash flow, but unfortunately West Bromwich Albion Football Club Ltd have not included a cash flow statement in their accounts since 2010.

DeleteYou can construct one yourself - it's not difficult. Even a bit of "Balls theory" would give the uneducated on the fans forums something to chew over. All they ever talk about is profit, and it isn't that relevant to a football club that write's down it's assets so aggressively.

DeleteOf course I could, but you will forgive me if I called it quits after 4,000+ words.

DeleteBy the way, while you're busy looking down on the "uneducated", you might want to check your grammar and in particular your rogue use of the apostrophe.

Yes, I may.

DeleteBut at least I understand what makes a business work, and it isn't profit.

Let me give you an example, sorry if I make it too simple for a great business mind like you.

Liverpool signed Andy Carroll for c£35M. They sold him a couple of years later for c£15M. They incurred a loss of £20M, and doubtless people like you will have been castigating them for losing £20M. The reality is in the year they sold him, they achieved an increased cashflow (spread over a couple of years) of £15M, that they could then invest in other players.

Profit is irrelevant in football, it's just a means of mitigating tax. Cash is king.

Yes, I think I understand cash flow:

Deletehttp://swissramble.blogspot.ch/2013/04/show-me-money.html

But I'm surprised that you give the Andy Carroll saga as an example of good business. Seriously?

The other element missing is how debt has been originated (and subsequently repaid) by sweating the club assets, in order to buy back share capital. This is where the majority of the increase in shareholding for Peace has been funded from. It has certainly not been funded from Peace privately buying shares.

ReplyDeleteThanks for this interesting piece, Rambler. I am probably one of the 'uneducated' ones, but do understand the fundamentals of good business practise, and you confirm my own opinion that WBA FC is an extremely well managed football enterprise. The club has paid its way without the benefit of a mega rich backer, and as a founding member of the Football League (one of twelve), can be proud of its past and present.

ReplyDeleteAs for Liverpool's loss on Andy Carroll apparently being cited as good business in another comment, well I never!

Nice blog, I have one question regarding the FFP rules. As far as I remember there is a limitation in the yearly increase in wages of 4M, as long as the increase does not come from other sources than broadcasting. It seems WBA increased the wages by 11.5M, while the only other revenue source that may have increased significantly is the player trading. (I guess the income statement is on calendar year while the transfer numbers are per season, so it is not clear to me how much the player trading revenue increased). Is this how the FFP works, or could WBA be violating the rules despite of their financial prudence?

ReplyDeleteThanks.

DeleteThat's pretty much right. Clubs whose player wage bill was more than £52 million in 2013/14 are only allowed to increase their wages by £4 million per season for the next three years. However this restriction only applies to the income from TV money, so any additional money from higher gate receipts, new sponsorship deals or profits from player sales can still be spent on wages.

There's also a question about the definition of wages here, i.e. if it excludes bonus payments, that would be beneficial to a club like West Brom, whose wages include a large performance-related element.