For a club of Aston Villa’s rich history, the past few years

have been profoundly depressing, as they have spent most of that time at the wrong

end of the Premier League table, desperately trying to avoid relegation. Their

managerial merry-go-round has failed to improve matters, merely bringing their

own version of doom (Alex McLeish) and gloom (Paul Lambert).

This has been matched by a dismal performance off the pitch

with the club bleeding money through some hefty losses, financed by the

American owner Randy Lerner pumping vast sums of money into Aston Villa – with

no tangible success. Little wonder that this toxic combination has caused

Lerner to put the club up for sale.

However, the mood has been a bit better at Villa Park since

the enthusiastic Tim Sherwood was appointed manager last month. There are also

some signs that there might be light at the end of the tunnel from a financial

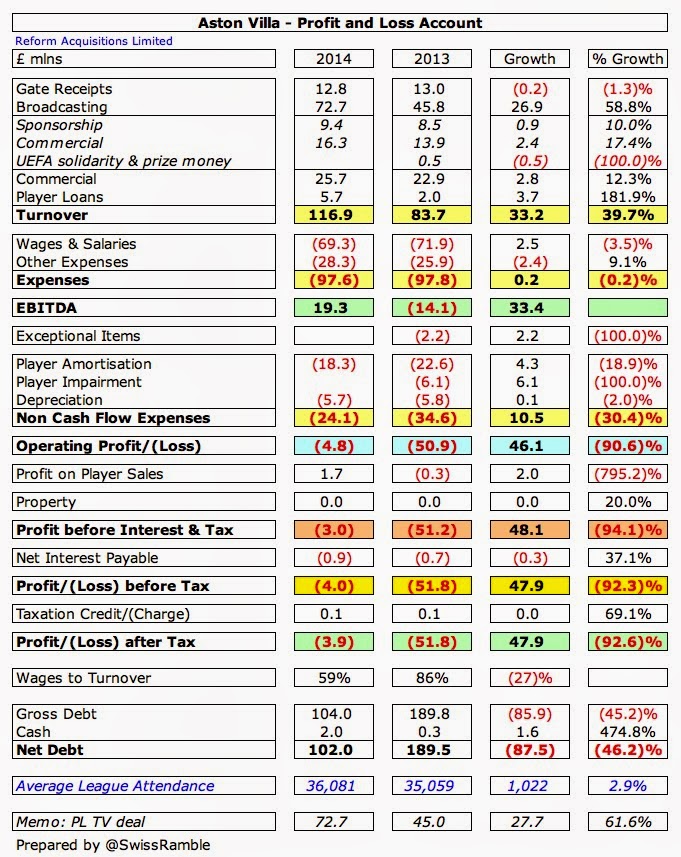

perspective, as Villa reported record revenue of £117 million in 2013/14, which

helped them reduce their loss before tax by a hefty £48 million from £52

million to just £4 million. We shouldn’t go overboard here, as Villa still lost

money, but it’s a step in the right direction.

The smaller loss was largely driven by the new Premier League

television deal, which was worth an additional £28 million to Villa, but there

was some useful revenue growth in commercial income £3 million and player loans

£4 million. Expenses were also cut, notably player trading costs by £10 million

(amortisation £4 million and impairment £6 million), wages by £3 million

and exceptional items (staff

termination and onerous contract costs) by £2 million.

The improvement was neatly summarised by chief financial

officer, Robin Russell: “By controlling costs we have been able to take

advantage of the new Premier League broadcasting deal to bring the club closer

to self-sufficiency.”

Russell added, “We are very pleased to be able to report

improved results after a period of heavy financial losses.” You can say that

again. Since Lerner bought Villa in July 2006, the club has accumulated losses

before tax of £222 million – nearly a quarter of a billion pounds. In the five

years between 2009 and 2013 alone the club lost £207 million, averaging £41

million a year. That’s an awful lot of money to finish 15th or 16th.

The best result in this period was a loss of “only” £18

million before tax in the 2011/12 season, but this was boosted by £20 million

of exceptional items and £27 million profits from player sales, so the underlying

figures were just as terrible as the other years.

The £20 million exceptional item refers to the once-off

waiver of interest on £107 million of loans provided by Lerner. Although the

club had been booking around £6 million of interest payable to the owner under

the terms of the loan agreement, he never actually took a cash payment.

On the other side of the coin, Villa also booked £26 million

of exceptional costs between 2011 and 2013, including £12 million in 2012

alone. These could justifiably be described as the costs of mis-management, as

these include termination payments made to sacked coaching staff and the

accounting cost of reducing the value of poor player purchases. There’s a price

to pay for constantly bringing in new managers, who will want to recruit their

own players, while getting rid of the deadwood accumulated by the previous

regime. As Orange Juice one sang, you have to “rip it up and start again.”

The 2011/12 season was also enhanced by a record-breaking £27

million profit on player sales, largely due to the big money moves of Stewart

Downing to Liverpool for £20 million and Ashley Young to Manchester United for

£17 million. In fact, this activity had been fairly lucrative for Villa,

earning them £79 million in the five years up to 2012. However, in the last two

seasons the well has run dry with the club earning less than £2 million from

player sales. The club argued that this was due to “the squad being rebuilt”,

but a less charitable interpretation might be that there were few players worth

buying.

Only four of the 15 Premier League clubs that have so far

published their 2013/14 accounts have reported a loss, which places Villa’s

improvement into context. The only clubs to have reported higher deficits than

Villa are Manchester City (£23 million), Sunderland (£17 million) and Cardiff

City (£12 million), who all have their own specific issues.

So, 11 clubs have made money (so far), largely off the back

of the new Premier League TV deal. In fact, five clubs have made profits of

more than £10 million: Manchester United £41 million, Everton £28 million,

Chelsea £19 million, WBA £13 million and West Ham £10 million.

Revenue rose 39% (£33.2 million) from £83.7 million to

£116.9 million in 2013/14, mainly coming from broadcasting, which was up 59%

(£26.9 million) from £45.8 million to £72.7 million. Fees for player loans rose

by £3.7 million from £2.0 million to a noteworthy £5.7 million, while

commercial income was also up 12% (£2.8 million) from £22.9 million to £25.7

million. Gate receipts were virtually unchanged at around £13 million.

Villa’s revenue has also grown by 39% since 2009, which is

another way of saying that there was zero revenue growth between 2009 and 2013.

Revenue had risen from £84 million in 2009 to £92 million in 2011, but there

was a reduction in revenue in 2012, largely thanks to worse performance on the

pitch (dropping from 9th to 16th place in the Premier League and early exits

from the cup competitions).

It should be noted that Villa changed the way they split their

revenue among the various streams in 2013, so they restated the 2012

comparative, but not prior years. This means that the apparent reduction in

match day income and consequent increase in commercial income since 2011 are

misleading.

In 2012/13, the last season where we have accounts for all

clubs, Villa’s revenue of £84 million was the 10th highest in the Premier

League. Their £33 million growth to £117 million in 2013/14 has been matched by

most other clubs, though they have overtaken West Ham.

There are two ways of looking at this. On the one hand,

Villa will struggle to compete at the highest level, as there is a financial

chasm between them and the top six clubs: Manchester United £433 million,

Manchester City £347 million, Chelsea £320 million, Arsenal £299 million,

Liverpool £256 million and Tottenham £181 million. United generate almost four

times as much money as Villa – their revenue is an incredible £316 million more

(for one season). On the other hand, Villa in turn earn more than clubs like Southampton,

Swansea City and Stoke City, so really should be performing better than them.

In fact, Villa are the 22nd highest club in the Deloitte

Money League, just ahead of famous clubs like Marseille, Roma and Benfica.

Great stuff, but the problem is that every other Premier League club is also in

the top 40 with 14 of them in the top 30, hence the club’s struggles in

England’s top flight.

Note that the Deloitte Money League excludes revenue from

player loans, so they have reduced Villa’s revenue of £117 million by £6

million to £111 million in their classification.

Villa’s reliance on TV money has become clearer than ever in

2013/14 with broadcasting accounting for 65% of total revenue (excluding player

loans), up from 56% the previous season. In this way, commercial income has

fallen from 28% to 23% and match day from 16% to 12%.

So Villa’s Premier League television money increased by 62%

(£28 million) from £45 million to £73 million in 2013/14. The distribution in

the Premier League is the most equitable in Europe with much of the money

distributed evenly between the 20 clubs. That is the case for 50% of the

domestic deal and 100% of the overseas deals.

However, 50% of the domestic deal depends on other factors:

(a) merit payments – 25% depends on where a club finishes in the league with

each place worth around £1.2 million; (b) facility fees – 25% is based on how

many times a club is broadcast live. This has really hurt Villa’s revenue over

the last few seasons, as they have dropped down the table.

As an example, if Villa had finished 6th in 2013/14, as they

did between 2007/08 and 2009/10, they would have received around £90 million,

i.e. £17 more than their £73 million. In fact, if Villa had maintained their

run of 6th place finishes in the four seasons since 2009/10, they would have

pocketed an additional £42 million. This highlights the tricky balance between

sustainable spending and investing for success. Spending money is obviously not

a guarantee, but a safety first approach can leave money on the table.

Of course, there will be even more money available when the

next three-year Premier League cycle starts in 2016/17 with the recently signed

extraordinary UK deals with Sky and BT producing a further 70% uplift. My

estimate is that a club that finishes 14th in the distribution table (as Villa

did in 2013/14) would receive around £110 million a season, which would

represent an additional £37 million.

The danger for Villa is that they would miss out on this

bonanza in the worst case scenario of relegation to the Championship. New chief

executive Tom Fox has stated that “relegation should not be in the lexicon of

Aston Villa”, but at this stage of the season this eventuality cannot be ruled

out.

Even though Villa would be protected to some extent by the

parachute payment of £24 million that would be added to the £1.9 million given

to all Championship clubs from the Football League’s own TV deal, they would

still have to contend with a £46 million cut in TV money. That’s a lot to

absorb, even if players have relegation clauses in their contracts.

Furthermore, Villa would have to quickly bounce back, as the disparity will

become absolutely colossal once the new 2016/17 TV deal kicks in, e.g. around

£72 million, even with an increase in the parachute payment.

Gate receipts fell very slightly by 1% (£0.2 million) from

£13.0 million to £12.8 million in 2013/14. This is around mid-table in the

Premier League, but importantly is significantly lower than the elite clubs,

e.g. both Manchester United and Arsenal earn over £100 million from match day

income (or eight times as much as Villa). A small part of this will be due to

the different ways clubs interpret match day income, but there is undoubtedly

an enormous difference.

Villa’s average league attendance of 36,081 was the 9th

highest in the Premier League, which is an impressive achievement considering

their problems on the pitch, but it is only 84% of the 43,000 capacity at Villa

Park. Only two other clubs in the Premier League had a percentage sold lower

than 90%: Sunderland 84% and Cardiff City 83%.

Villa’s attendance actually increased in the last two

seasons, having steadily declined from the 40,000 peak in 2007/08, though it

has once again fallen this season to around 33,000 (as of 20 March 2015). That

represents an 18% fall and 7,000 fewer fans (or customers, to put it into

financial terms). This has clearly hit the club’s finances, as has the limited

progress in cup competitions, e.g. in 2009/10 Villa reached the Carling Cup

final and the FA Cup semi-final, which had a beneficial impact on match day

revenue.

Commercial revenue rose by an encouraging 12% (£2.8 million)

from £22.9 million to £25.7 million, comprising £9.4 million sponsorship and

£16.3 commercial income. This is almost exactly the same as Newcastle United’s

£25.6 million, but (stop me if you’ve heard this one before) is significantly

lower than the top six clubs. For example, Manchester United’s commercial

revenue is up to £189 million, more than seven times as much as Villa, followed

by Manchester City £166 million, Chelsea £109 million, Liverpool £104 million,

Arsenal £77 million and Tottenham £45 million.

The disparity is most evident when comparing the shirt

sponsorship deals. Villa have a two-year deal with Dafabet, an Asian online

betting website, worth £5 million a year that runs until the end of this

season. This looks very low compared to the major clubs, who continue to

increase their deals, e.g. Manchester United and Chelsea have both announced

huge new deals recently, United for £47 million with Chevrolet and Chelsea for

a reported £38-40 million with Yokohama Rubber.

It’s a similar story with Villa’s kit supplier, Macron, who

have a four-year deal worth £15 million (£3.75 million a year), running until

the end of the 2015/16 season. Not bad, but it pales into significance next to

match Manchester United’s “largest kit manufacture sponsorship deal in sport”

with Adidas, which is worth £750 million over 10 years or an average of £75

million a year from the 2015/16 season.

In fairness, most clubs outside of the absolute elite have

struggled to secure such massive deals and Villa would have to enjoy a

sustained run of success to substantially improve their commercial deals.

They are placing a lot of hope in Tom Fox, who was previously

the chief commercial officer at Arsenal. Although he has arrived with a solid

reputation on the back of signing two substantial sponsorship deals with

Emirates and Nike, some fans of the North London club were disappointed in his

lack of progress in securing secondary sponsors. He will have to go some to

significantly grow Villa’s commercial income, though there has been talk of

selling naming rights to the famous Holte End stand.

Villa cut their wage bill by 4% (£2.5 million) from £71.9

million to £69.3 million in 2013/14, reducing the wages to turnover ratio from

86% to 59%. In fact, wages have fallen by 17% (£14 million) from the peak of

£83.4 million in 2011. Since then Villa have “rationalised the playing squad”

and exercised “tight control of players’ wages”, so that the wage bill has been

held at around £70 million, despite £25 million of revenue growth in the same

period. To be fair, the wages to turnover ratio was an unsustainable 91% in

2011.

In 2012/13 Villa’s wage bill was the 8th highest in the

Premier League, only behind the usual suspects plus the basket case known as

QPR. However, they are one of the few clubs not to substantially increase their

wages in line with the new Premier League TV deal, so in 2013/14 they have been

overtaken by Sunderland and largely caught up by the likes of Everton, WBA,

West Ham and Swansea City. Of course, the “big boys” are nearly out of sight:

Manchester United £215 million, Manchester City £205 million, Chelsea £193

million, Arsenal £166 million and Liverpool £144 million.

It is instructive to compare Villa’s wages with Tottenham, a

club with similar aspirations. Back in 2008, both clubs had a wage bill around

£50 million before Villa initially surged ahead in the next two seasons.

However, Villa’s relative austerity since then has resulted in Tottenham’s

wages being £24 million higher in 2012/13 and I suspect the gap will be even

higher when Spurs publish their 2013/14 accounts.

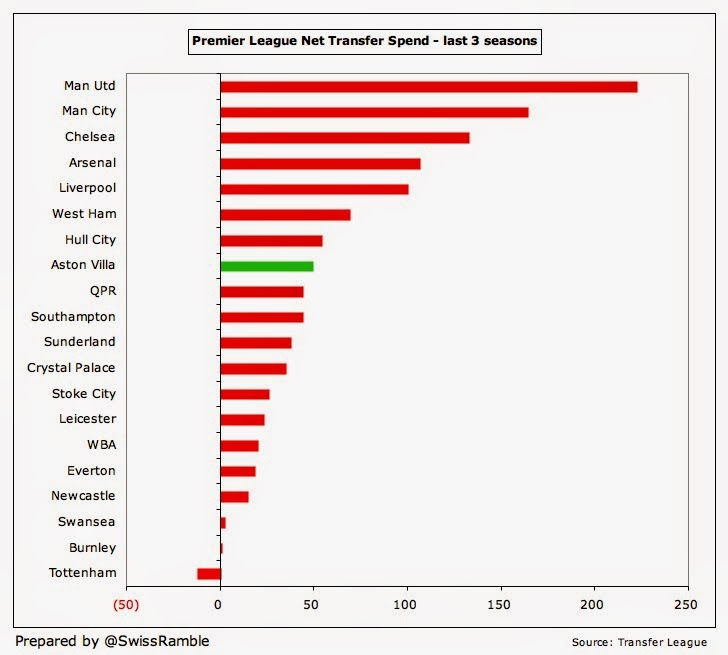

There is one myth that should be nailed, namely that Randy

Lerner has not funded transfers since the profligate Martin O’Neill era. It’s

true that there was a slowdown in the following two seasons, but Villa have a

net spend of £49 million in the last three seasons, averaging £16 million a year. This compares pretty favourably

with the £84 million O’Neill spent in four seasons or £21 million a year. As

the wonderfully named director General Charles Krulak explained: “The idea that

Randy had not put money into the club and that Paul Lambert’s hands were tied

is simply not true. It’s hogwash.”

Obviously this £49 million net spend is way below the

expenditure in the same period by the leading clubs such as Manchester United

£222 million, Manchester City £164 million and Chelsea £132 million, but it was

still the 8th highest in the Premier League and fans are entitled to expect a

bit more bang for their buck. In fairness, the figures are a little misleading,

as only one player, Christian Benteke, arrived for a sum above £5 million, so

the suspicion is that many ordinary purchases have been made. As the club’s

accounts once put it: “The acquisition of players and their related payroll

costs are deemed the core activity risk and… the directors are mindful of the

pitfalls that are inherent in this area of the business.”

Villa’s net debt was slashed by £87.5 million from £189.5

million to £102.0 million, mainly due to Lerner converting £90 million of loan

notes into share capital in December 2013, “reducing the club’s debt load and

accelerating the process towards long-term stability and financial

self-sufficiency.” Gross debt of £104 million mainly comprises owner debt of

£86 million (£69 million owed to the parent undertaking and £17 million of loan

notes), though the bank loan and overdraft is up from £13.6 million to £18

million.

Potential additional transfer fee payments (based on

contractual conditions such as number of appearances and retention of Premier

League status) decreased from £8.4 million to £4.2 million, though there are

now also contingent liabilities of £2.75 million payable upon the change of

ownership of the football club.

Although Randy Lerner did not inject any additional funds

into Villa in 2013/14, he has been a most generous owner. On top of the initial

£66 million paid to acquire the club in 2006, he has put in the best part of

£300 million, split between £125.5 million of share capital, £114.5 million of

loan notes and £46 million loans from the parent undertaking. In addition, he

has cancelled repayment of £97.5 million of loans.

According to the club, Villa should have no problems with Financial Fair Play: “In terms

of regulations, players’ payroll for the year complies with the Premier

League’s Short Term Cost Control Rules and forecast results for the three years

ending 31 May 2016 currently meet the Premier League’s Profitability and

Sustainability Rules.”

Villa will have to be aware of the restriction whereby clubs

whose player wage bill is more than £52 million will only be allowed to

increase their wages by £4 million per season for the next three years. This

only applies to the income from TV money, so if Villa want to “go for it” and

substantially increase their wages, they will have to grow revenue via new

sponsorship deals, higher gate receipts or profits from player sales.

It is difficult to know what Villa can do to improve their

situation. Initially under Lambert, they appeared to be following a youth

policy, but that appears to have been largely abandoned. There are a couple of

youngsters like Jack Grealish, Callum Robinson and Lewis Kinsella coming

through, but Villa’s academy does not seem to be as successful as it has been

in the past in producing talented youngsters.

"Big Ron"

Randy Lerner appears to have had enough, which is hardly

surprising after he has spent so much for so little return on the pitch.

Effectively, Villa are back to where they were when he acquired them. In May

2014, he put the club up for sale and you could feel the man’s pain: “I have

come to know well that fates are fickle in the business of English football.

And I feel that I have pushed mine well past the limit. I owe it to Villa to

move on, and look for fresh, invigorated leadership, if in my heart I feel I

can no longer do the job.”

He put the prospective sale on the back burner last summer,

basically after no buyer could be found, but there are whispers that talks are

ongoing with potential purchasers. Any deal would surely only take place in the

summer after Villa’s fate is known, as relegation would severely impact the

price.

The club has gambled on reducing the investment in the

playing squad, especially with the tightly controlled wage bill, as it focuses

on a sustainable future, which is an admirable strategy – so long as it does

not backfire and result in the dreaded relegation. Tom Fox summed up the club’s

(modest) ambition: “We’ve got by far the best house on the worst street in

town. Our aim is to get to be the smallest house on the best street and try to build

it up from there.” After many managerial debacles, Villa’s supporters will hope

that Tim Sherwood is indeed the right man for the job.

You misquoted Fox at the end there. He said the next target for Villa was to become the "smallest house on the best street and build from there." Fox reckons Villa are eight years behind the current top six which indicates the pig's ear Lerner has made of it all.

ReplyDeleteNew owners and sponsorship deals more fitting for a club of Villa's size and history could very quickly turn these figures around.

Thanks for the analysis.

Ah, yes. You're right. Missed out an important word there. Now corrected. Thanks for the tip.

ReplyDeleteDoes Crystal Palace not release revenues?

ReplyDeleteI think this is a fantastic article. I've been waiting for this since the accounts came out.

ReplyDeleteOne thing which would be a great addition is looking a bit more to the future.

Yes we made a £4m loss but that is almost exactly the annual cost of Darren bent, who's contract finishes this summer. Shay given still a great asset is on a large deal also due to finish.

Essentially promoting a youth striker and utilising our other keeper would mean we maintain the squad and also save a whopping £7m+ per year through those two salaries leaving the club.

Add to that (hopefully) a nice sponsorship increase of a similar 12% we suddenly find ourselves making a nice little bit of money.

The key is to mix youth with much fewer but higher quality signings.

Comparing against the top six whilst useful to show the difference in the premier league isn't really what I was looking for. More about how we fit with the rest and why we shouldn't (at least) be finishing 7-8 each year.

The problem is that there are seven clubs (Everton, Southampton, Swansea, West Ham, Stoke, Newcastle, and Aston Villa) who think they should be finishing 7-8 (or better) each year. Luck and competency will decide which ones succeed in this ambition. Aston Villa has lacked both recently.

ReplyDeleteLooking forward to your update following the take over

ReplyDelete