So Celtic duly won their fourth consecutive Scottish League

title in May in their first season under young Norwegian manager Ronny Deila,

who had replaced the very successful Neil Lennon the previous summer.

Despite this fine achievement, there was also

disappointment, as the famous Glasgow club failed to qualify for the group

stages of the Champions League, even though they had two bites at the cherry,

having been reprieved after Legia Warsaw fielded an ineligible player, only to

crash out against Slovenian champions Maribor.

This was in stark contrast to previous great nights in

Europe. As recently as November 2012, Celtic beat Barcelona 2-1 in front of a

packed Celtic Park, as they made their way to the last 16 of the Champions

League. Many believed that this would be the platform for greater things, but

the club has not progressed since then, as they did not make the best use of

the European cash windfall. Instead, they sold three key players at the end of

that season (Victor Wanyama, Gary Hooper and Kelvin Wilson) and failed to

adequately replace them.

Although this might be considered a lack of ambition on

behalf of the Celtic board, it also comes down to a simple lack of money. On

the face of it, the club’s finances look pretty good, as they are consistently

profitable and have little debt, but if you dig a little deeper, then Celtic’s

financial challenges become all too apparent. As Deila beautifully put it,

“Celtic is unbelievably huge, but the money here is not so huge.”

Nevertheless the most recent published accounts from the

2013/14 season featured a £1.4 million increase in profit from £9.7 million to

£11.2 million, despite revenue falling by £11 million (15%) from £76 million to

£65 million. The club described these results as “impressive particularly given

the difficult economic climate”, but they were largely boosted by profits on

the aforementioned player sales, which rose £12 million from £5 million to £17

million.

In addition, the wage bill was cut by £3 million (7%) to £38

million, though an impairment charge of £4 million was booked to reduce the

value in the accounts of certain players. There was also an exceptional payment

of £0.6 million for contract termination, though this was lower than the previous

year’s exceptional items of £1.3 million, which were mainly for an onerous

lease provision for certain loss-making retail stores.

Celtic’s 2013/14 £11.2 million profit was easily the best

financial result in the Scottish Premiership – even though Hearts reported a

£26.8 million profit, this was inflated by a £27.5 million credit for a

write-off in respect of the Creditors Voluntary Agreement. Most other clubs

reported (small) losses with only Dundee United and St Johnstone recording

profits.

Of course, Rangers are no longer in the top division, which

is something of a double-edged sword for Celtic. A couple of years ago, chief

executive Peter Lawwell insisted that they did not need the presence of Rangers

to flourish financially after their rivals’ off-pitch problems meant no definite Old Firm derbies for a few years.

He said, “We look after ourselves. We don’t rely on any

other club. We are in a decent position, we’re very strong.” That’s all well

and good, but it could be argued that a lack of strong domestic competition may

leave Celtic ill prepared for their European campaigns – and that’s where the

big money lies.

That said, Celtic have maintained a relatively strong

financial position, making profits in six out of the last eight years. Even

though these have not been enormous sums, the aggregate profit since 2007 is a

tidy £33 million. This is a result of the club’s prudent approach, as outlined

by chairman Ian Bankier: “The club, financially, has to adopt a self sustaining

model. In plain words, we have to live within our means. We cannot spend money

that we don’t have.”

Specifically, the club’s “core business strategy… relies

upon: the youth academy; player development; player recruitment; management of

the player pool; and sports science and performance analysis; to deliver long

term sustainable football success.” In short, the club will stand or fall on

how successful it is in buying players (relatively cheaply) and/or developing

its youngsters.

Of course, these figures might provoke the question of why

the club does not put more of its profits on the pitch, but these surpluses are

largely driven by two factors: (a) player sales; and (b) money from competing

in Europe, especially the Champions League.

As Lawwell said, “Player transfers have been an increasingly

important element of our business for a number of years.” He recently confirmed

the value of this activity, “Significant income was brought into the club

as a consequence of transfer fees received.”

In fact, if player sales were to be excluded from Celtic’s

figures, they would actually report a loss most years, e.g. the 2013/14 profit

of £11.2 million would have been a loss of £5.9 million without the £17.1

million profit on player sales.

Similarly, the club would have made a loss in 2011 instead

of breaking-even without the £13.2 million profit from the sales of Aidan

McGeady, Artur Boruc, Marc-Antoine Fortuné and Stephen McManus. Perhaps most

tellingly, Lawwell noted that the club could have eliminated the (£7.4 million)

loss in 2012 by selling players – though they were retained as a deliberate

policy “in order to achieve strategic objectives”, i.e. progress in Europe.

Since 2007 this player trading activity has generated £61

million of accounting profits. However, these are not the same as cash profits,

as the accounts include many non-cash items, such as depreciation, player

amortisation, impairment and exceptional provisions.

To get an idea of how the club’s underlying business is

doing, we can look at its operating profit. This has steadily declined from £16

million in 2007 to a loss of £3 million in 2012, though the 2013 Champions

League run reversed the trend pushing operating profit back up to £13 million,

before once again falling in 2014 to £5 million.

The 2014/15 results will again highlight the need to sell

players in more difficult seasons. Participation in the Europa League as

opposed to the far more lucrative Champions League, will mean a steep reduction

in revenue, but this will be partly offset by the sales of Fraser Forster and

Tony Watt “for sums well in excess of book value.”

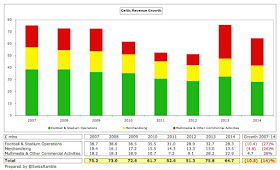

Basically Celtic are constrained by their lack of revenue

growth. In 2013/14 revenue fell 15% (£11 million) from £76 million to £65

million with all three operating divisions decreasing: football and stadium

operations by 14% (£4.4 million) from £32.7 million to £28.3 million;

merchandising by 10% (£1.5 million) from £15.0 million to £13.5 million; and

multimedia and other commercial activities by 19% (£5.2 million) from £28.2

million to £22.9 million.

In fact, Celtic’s revenue has actually fallen by 14% since

2007 with only multimedia and other commercial activities growing in this

period, while the other two divisions each dropped by a hefty 26-27%.

This disappointing revenue performance highlights Celtic’s

issues perfectly, as it can be considered from two very different aspects, i.e.

domestically and on the international stage.

Even after the fall in revenue, Celtic’s £65 million is

still by far the highest revenue in the Scottish Premiership with the nearest

challenger being Aberdeen’s £11.2 million, more than £50 million lower. All the

other clubs only generate £3-7 million a year. In fact, Celtic earn £10 million

more than all the other clubs in Scotland’s top tier combined.

However, while Celtic’s revenue has stagnated, other leading

clubs have seen their turnover explode in the last few years. The last time

that Celtic featured in the annual Deloitte Money League was 2007 when their

£75 million was the 17th highest in the world, but they are now miles behind Europe’s

elite.

In the last seven years Celtic’s revenue fell £11 million,

while almost all other clubs have benefited from significant growth. As an

example, the top four (Real Madrid, Manchester United, Bayern Munich and

Barcelona) have all seen their revenue increase by more than £200 million.

As a (slightly) more realistic comparison, Celtic’s revenue

was within striking distance of Juventus in 2007, being £23 million below the

Italian giants’ £98 million, but the gap has now widened to a vast £169 million

(£234 million vs. £65 million).

Much of this is down to the disparity in the television

deals, as seen by the rise of English clubs with 14 in the top 30 (and all 20

Premier League clubs in the top 40). If we take Everton as an example, we can

see that their revenue was £24 million lower than Celtic’s in 2007, but they

have surged past them following three new TV deals (in 2008, 2011 and 2014) and

their revenue is now £56 million higher at £121 million.

Multimedia and Other Commercial Activities revenue has risen

since 2007, but it’s been a bit of a rollercoaster ride, as it is highly

dependent on TV money from European competitions. As the annual report stated,

“The trading results emphasise the significant benefit from participating in

the group stage of the UEFA Champions League.”

Celtic achieved this objective in the last two seasons,

receiving around £35 million in prize money alone in those two seasons (£20

million in 2013 and £15 million in 2014). This is essentially the difference in

revenue compared to the previous three seasons, when receipts were restricted

by the much smaller amounts distributed by the Europa League. The impact would

be even greater if additional match ticket sales and the impact on commercial

deals were considered.

The highest payment Celtic received came in 2013 as a result

of performing well in the group, which was worth €3.5 million (3 wins at €1

million, 1 draw at €500,000), and reaching the last 16 for another €3.5

million. This was added to the €8.6 million that all teams received for

reaching the group stage and €8.1 million from the TV (market) pool. That gave

a very nice total of €23.7 million – or £20 million.

It should be noted that the prize money is denominated in

Euros, so the exchange rate is also a factor. As Sterling strengthens, the

amount booked in Celtic’s accounts will decrease.

What is striking is that if European prize money is

excluded, then Celtic’s other income is on an obvious downward trend, e.g. from

£65 million in 2007 to £50 million in 2014. Little wonder that a few years ago

Lawwell observed, “Clearly, European progression is key in enabling the club to

achieve its financial objectives.”

The importance of qualifying for the Champions League has

been further underlined with the new deal from the 2015/16 season that will

increase the prize money by an estimated 50% with further significant growth in

the TV (market) pool. Europe League payments will also rise, but it will still

be very much the poor relation.

Celtic’s Achilles heel is obviously the Scottish TV deal,

which is worth a paltry £15 million a year – and that is for all Scottish

professional clubs. As Lawwell said, “We play in a country of five million

people. We’ve got the media values that represent that.” The distribution is

determined by reference to the league position, so Celtic have been receiving

more money than other clubs, but this was still only worth a feeble £2.4

million in 2014/15.

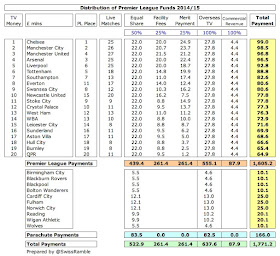

To place that into context, Queens Park Rangers “earned” £65

million for finishing bottom in the Premier League the same season, while title

winners Chelsea received £99 million. Championship clubs that receive parachute

payments following relegation from the English top flight received nearly £27

million, while even a normal Championship club gets more than Celtic with £4

million.

This massive inequality is keenly felt by Celtic, as Bankier

noted: “The harsh reality is that the total income from broadcasting rights

available to the Scottish game is a tiny fraction of what is available to our

neighbours in England.” He’s not kidding – the Scottish deal is worth less than

1% of the Premier League deal and that is before the estimated 50% rise in

2016. In fact, broadcasters pay more to show two English games than an entire

Scottish season.

The current Scottish TV deal runs to 2017, but it is

reported that Sky have an option to extend the contract for a further three

years, so there is little that can be done for a while. England may be the

colossus when it comes to TV rights, but other smaller countries are also doing

better than Scotland: Belgium £40 million, Norway £34 million, Greece £30

million and Austria £15 million. The fact is that broadcasters do not regard

Scottish football as an attractive product without the pull of guaranteed Old

Firm derbies.

Football and Stadium Operations is the largest business

segment at Celtic with £28.3 million in 2014, though this was 14% (£4.4

million) lower than the previous year. This is essentially match day revenue

plus money generated by the Celtic Park stadium on other occasions.

The reduction in income was mainly due to less match tickets

income, including corporate and premium sales, following the £100 reward to

adult season ticket holders “for their continued support”, as well as lack of

progression to the Champions League knockout stages and failure to make the

latter stages of both domestic cup competitions.

This revenue stream has been reducing for some time, partly

due to a smaller number of home matches, especially the money-spinning European

ties, but also in line with lower average attendances. These have fallen from

over 58,000 in 2005/06, when Celtic enjoyed the third highest crowds in the UK,

to under 44,000 in 2014/15.

There is little doubt that the Celtic supporters are

extremely important to the club, as former chairman John Reid noted: “They do

not show up on a balance sheet. But they are an invaluable asset, the very

lifeblood of a club like Celtic.” It must therefore be of concern to the club’s

hierarchy that attendances are not what they once were – even with over 40,000

season ticket holders

The lack of matches against Rangers has surely had an impact

on these figures, as Lawwell explained, “If you have more meaningful games,

then you have more people turning up and that means more cash at the gate, more

sponsorship interest and more TV interest.”

Furthermore, Celtic’s attendance is still the highest in

Scotland with their 2013/14 average of 46,000 being more than 30,000 higher

than Hearts in the Premiership, though Rangers attracted a notable 43,000 in

League One.

Interestingly, Celtic have just announced that they have

been granted permission to introduce safe standing for up to 2,600 supporters,

using the rail seating system which can be found in stadiums in Germany.

Merchandising revenue dropped 10% (£1.5 million) from £15.0

million to £13.5 million in 2014, a long way below the peak of £18.4 million in

2007. This revenue stream is heavily dependent on the relative popularity of

kit launches, though the slight rebound in 2013 was driven by Champions League

success and 125th Anniversary products.

Lawwell said that the club is “committed to the development

of the Celtic brand, including the improvement of the match day experience for

our supporters at Celtic Park”, such as the opening of Celtic Way. This was

showcased in the opening ceremony of the Glasgow 2014 Commonwealth Games. The

chief executive added, “I think our story is unique, I think it is rich, it’s

the best and we have a potential fan base of Scots and Irish around the world

that would support that.”

"Jackie Wilson Said (I'm In Heaven When You Smile)"

That said, the club did note that “the sponsorship landscape

remains extremely challenging” and the “business environment and economic

difficulties continue to impact upon companies’ advertising and marketing

budgets.”

It must have therefore been very pleasing for Celtic to sign

a three-year shirt sponsorship deal with Magners in 2013/14 for a higher sum

than the £1.5 million paid by the previous sponsors Tennent’s. That brought to

an end to the joint sponsorship arrangement with Ranger, so the two sides had

different shirt sponsors for the first time in 13 years.

Moreover, Celtic have recently announced a new kit supplier

deal with New Balance that will start from the 2015/16 season, which is worth a

sum “significantly higher” than the long-standing agreement with Nike. The club

has not divulged any financial details, but the annual payment is reportedly

increasing from £5 million to £5.8 million.

The wage bill was cut by 7% (£3.0 million) from £40.7

million to £37.8 million, due to “the change in player personnel” and lower

bonus payments based on Champions League progress. In fact, wages have hardly

grown at all in recent years, only rising by 4% (£1.3 million) since 2007.

Following the revenue decrease, the wages to turnover ratio

rose from 54% to 58%, which is among the lowest in the Scottish Premiership,

though a fair bit higher than Hearts’ 44%. This is in line with the majority of

Premier League clubs in England, where the average has come down to 59% as a

result of the higher TV money.

Given the differences in revenue, it is no surprise that

Celtic’s wage bill of £38 million is by some distance the highest in Scotland’s

top tier, more than six times as much as Aberdeen’s £6 million. In fact, their

wage bill is more than the other 11 clubs combined.

However, this would be the lowest wage bill in the Premier

League behind luminaries like Hull City £43 million, Crystal Palace £46

million, Norwich City £50 million and Cardiff City £53 million. Obviously,

Manchester United are quite literally in a different league with a wage bill of

£215 million, but it is also worth noting that Celtic were only just ahead of

some clubs in the Championship, e.g. Leicester City £36 million, Reading £35

million and Blackburn Rovers £34 million.

As the 2014 accounts drily noted, “Player wages are subject

to market forces with wage levels in some countries, particularly in those

leagues with lucrative broadcasting contracts, significantly exceeding those

available in others.” You can say that again.

Actually, Lawwell had said much the same thing in even

starker terms a couple of years earlier: “Wage and transfer fee inflation over

a number of years means that the gap between Scotland and the major European

footballing nations is impossible to bridge, thus the relative cost and

challenge of attracting quality players gets no easier.” Deila also now fully

understands the problem: “You have to see the big picture. It is not about the

(transfer) fee, it is about the salaries.”

To reinforce this point, it is worth again comparing Celtic

with Everton. Their wage bills were almost exactly the same back in 2007, but

Everton’s has risen by 80% to £69 million, while Celtic’s growth was only 4% to

£38 million.

There is one Celtic employee that seems immune to wage

restraint, namely the chief executive, who trousered just under £1 million for

the second year in a row. This included a £400,000 bonus payment, even though

his contractual maximum bonus payment should be 60% of his salary of £525,000,

i.e. £315,000. Happily for Mr. Lawwell, the Remuneration Committee decided to

make an additional bonus award on an ex

gratia basis. While he is no doubt very good at his job, this does

seem a bit steep, when the rest of the wage bill is under so much pressure.

Celtic have been consistent spenders in the transfer market

over the years, but not that much - and net expenditure has reduced in recent times. If we divide

the last 12 seasons into three periods of four years, the difference is

striking: 2002-06 £14 million; 2006-10 £18 million; and 2010-14 just £1

million.

There has also been a subtle change in the chairman’s

statements. In the 2012 accounts he said, “We continue to make sizeable

investment in new players, so as to strengthen the squad with a view to achieve

our primary objective”, which was described as to win the Scottish title and to

reach the group stages of the Champions League. However, in 2014 this had been

toned down to: “We do the utmost to acquire the best players we can with our

financial constraints.”

According to Lawwell, the strategy has been to “scour the

world for talent to develop”, which means building a world-class scouting

network that can look at undervalued markets in Scandinavia, Latin America,

Africa and Asia. There is nothing wrong with this plan, given Celtic’s

financial challenges, and it looked to be working well for a while.

However, it is debatable whether the club has spent its

money wisely in recent times, though in fairness it has been hard to find

value-for-money purchases, when so many clubs are trying to do exactly the same

thing. In addition, it must be difficult to attract players to what is

effectively a one-team league when the wages on offer are nothing special, so

Celtic often have to take a punt on comparative unknowns.

Hence, they have started to make extensive use of the loan

market, bringing in the likes of John Guidetti and Jason Denayer from

Manchester City and Aleksander Tonev from Aston Villa on season-long loans last

year.

Celtic have gross debt of £11.0 million, which means that

they have net funds of £3.7 million after taking £14.7 million of cash balances

into consideration. The gross debt comprises £10.2 million of bank loans, a

£0.7 million overdraft and other loans of £0.1 million. This is obviously a

pretty healthy position, especially as gross debt was as high as £19.7 million

in 2005, though Lawwell noted that the club has “fluctuating cash requirements”

during the year, so they had a net debt position of £6.5 million during

2013/14.

There has been some confusion over Celtic’s reported debt

figures, as the accounts refer to a debt facility with the Co-operative Bank of

£32.4 million, made up of £20.4 million long-term loans and a £12 million

overdraft.

The loan agreement is further split between a revolving

credit facility of £6.0 million (base rate + 1%) and long-term loans of £14.4

million (LIBOR + 1.125%). These are repayable in equal quarterly instalments

form October 209 to April 2019 with any balance repayable in July 2019, though

there is an option to repay the loans early without penalty. These loans are

secured on Celtic Park and the land adjoining the stadium and at Westhorn and

Lennoxtown.

"Pass the Dutchie"

The important point is that this is a loan facility, as

opposed to loans actually taken out. In fact, the accounts clearly state that

£22.2 million of the available bank facilities of £32.4 million remained

undrawn at the balance sheet date, which reconciles perfectly with the bank

debt of £10.2 million.

In addition, the balance sheet includes £4.3 million for the

debt element of Convertible Cumulative Preference Shares. These carry the right

to a 6% dividend (around £0.5 million a year), which has been paid since 1997.

There are also contingent liabilities, i.e. transfer

payments dependent on criteria like number of appearances, of £3.6 million,

with contingent assets of £2.3 million. The accounts note that £5.0 million has

been committed on player purchases and loans since the accounts closed, though

there have also been sales proceeds of £8.1 million.

The board has been accused of hoarding cash, but that is not

really the case if we look at the cash flow statement. Over the last eight

years Celtic have generated a total of £62 million from operating activities,

but have then spent a net £19 million on players and £21 million on

infrastructure, such as improvements in the stadium and the Lennoxtown training

facility.

They have then spent a further £4 million on debt repayment,

£2 million on interest and £4 million on dividends, leaving a net £11 million

increase in cash balances. Lawwell has promised that “the board will re-invest

every penny received back into the club for the longer-term.” Given the

fluctuations in cash levels during the year, the club is more or less living up

to that promise. Whether they should be more ambitious and extend their debt is

another question, though Rangers’ demise is a powerful warning against

over-extravagant behaviour.

"Fanfare for the Commons man"

One approach Celtic has taken to address its issues with

salary and transfer costs is investment in youth development, so that a greater

number of players can be “internally generated”. A key element of that strategy

is the partnership with St Ninian’s High School in Kirkintilloch, which is now

in its seventh year.

Lawwell said that the club “decided to take significant funds

from our first team in 2006/07 and to reinvest it in building a

state-of-the-art training campus and developing a youth academy.” He added,

“It is all about building a sustainable, long-term economic model which will

buttress us from the effects of any sudden downturns. It is designed to ensure

that we remain competitive in elite European competition.”

And that’s the key point: Celtic need to be successful in

Europe (i.e. reach the Champions League group stages) to generate decent

revenue. In order to give themselves the best chance of achieving that

objective, they need to spend a reasonable amount of money to compete with

wealthier clubs. However, they need to do that within their limited budget.

"A Forrest"

As Lawwell stated, “The funding of that success must recognise

the financial constraints applicable to the organization, particularly as

Celtic continues to play in the Scottish football environment and the

challenges that presents.”

So, it’s a case of damned if they do, damned if they don’t.

After a mixed first season, Ronny Deila now needs to

demonstrate his worth and take the club forward. As we have seen, in the modern

era that’s easier said than done, given Celtic’s diminished resources, but when

Celtic Park is in full voice on a European night, anything seems possible.

Says it all really, and helpfully puts some concrete numbers to what those of us who watch the Scottish game already know.

ReplyDeleteThe tables showing that Celtic have more revenue than every other club in the SPL put together, and also pay wages greater than all of their rivals in that division put together, speak volumes about how completely predictable that competition is. Winning the league is therefore no credible achievement at all. Indeed any Celtic manager who failed to land the Scottish title with those massive structural advantages in his favour would merely be demonstrating his utter incompetence.

And no prizes for guessing, given the dire quality of the SPL and the certainty about who'll be champions every year, why the broadcasters are happy to pay more for a couple of Barclays Premier League matches in England than they wll for an entire season in Scotland's top flight.

Poor Celtic!! More money than all the other teams put together and they miss their mates!!

DeleteHopefully between Aberdeen, Dundee Utd, Hearts and St Johnstone we can all take points off them and preferably for me, Aberdeen win the league. Could we not get rid of Doncaster and Reagan who never seem to find fault with what is happening at Ibrox but punish other teams for the slightest discrepancy.

Rangers vs Celtic - What was once a formidable sporting rivalry is now a fading memory.

ReplyDeleteI'd wager that most Celtic fans voted "Yes" to Independence and most of them are probably a lot more anti-Britain than everbody else in Scotland. BUT, if the chance came up for their beloved team to join the English Premiership, they'd be in there in a shot.

ReplyDelete