This season has seen a return to form for Chelsea following

the appointment of Antonio Conte. The former manager of Italy is famed for his

passion, but also possesses much tactical astuteness, as evidenced by

previously leading Juventus to three consecutive Serie A titles. Under his guidance, Chelsea are currently setting

the pace and look a very good bet for the league title.

This demonstrates just how quickly things can change in

football, as the 2015/16 season was Chelsea’s worst in the Roman Abramovich era

with the club slumping to a disappointing tenth place in the Premier League,

thus failing to qualify for Europe for the first time in 20 years. This

inevitably resulted in the departure of José Mourinho, the self-proclaimed

“special one”, with the reins handed to Guus Hiddink until Conte’s arrival.

This dismal performance was matched off the pitch with the

2015/16 accounts revealing a £70 million pre-tax loss, around £49 million worse

than the previous season’s £21 million deficit.

In fairness, this was predominately due to £75 million of

exceptional expenses, largely £67 million to terminate the Adidas kit supplier

contract in favour of a significantly more lucrative deal with Nike, plus £8

million compensation to Mourinho and his team. Without these exceptionals,

Chelsea would have reported a profit before tax of £5 million.

Revenue rose £15 million (5%) to a record level of £329

million, as commercial income increased by £9 million (8%) to £117 million

following the new shirt sponsorship with Yokohama Tyres.

Broadcasting income was also up £7 million (5%) at £143

million with the higher UEFA deal increasing Champions League distribution by

around £20 million, though this was partly offset by the £12 million reduction

in Premier League TV money due to the lower league finish. Gate receipts fell

slightly by £1 million to £70 million.

"U Got The Look"

In addition, profits on player sales increased by £8 million

to an impressive £49 million, principally due to the sales of Ramires to

Jiangsu Suring, Petr Cech to Arsenal, Mo Salah to Roma, Oriol Romeu to

Southampton and Stipe Perica to Udinese.

In contrast, the wage bill rose by £7 million (3%) to £222

million, while player amortisation also increased £2 million (2%) to £71

million, though other expenses were £11 million lower at £71 million.

It is also worth noting the enormous £29 million loss that

Chelsea made on cash flow hedges, as FX movements dramatically reduced the

value of their forward currency contracts, presumably due to Brexit. This took

their comprehensive loss to £99 million.

For comparison, Manchester United reported a similar £38

million loss on cash flow hedges, while this was not yet an issue for Arsenal

or Manchester City, whose accounts closed on 31 May (i.e. pre-Brexit).

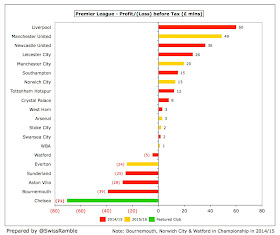

Chelsea’s £70 million loss is likely to be the worst

financial performances in England’s top flight in 2015/16. The only other club

to have announced a loss so far is Everton with £24 million.

In contrast, six of the eight Premier League clubs that have

published their accounts to date for last season have reported profits, the

largest being Manchester United £49 million, Manchester City £20 million and Norwich

City £13 million, followed by Arsenal £3 million, Stoke City £2 million and

West Bromwich Albion £1 million.

Although football clubs have traditionally lost money, the

increasing TV deals allied with Financial Fair Play (FFP) mean that the Premier

League these days is a largely profitable environment with only six clubs

losing money in 2014/15. This group largely comprised clubs that have been

badly run (Aston Villa, Sunderland and QPR), but also included Manchester

United, Everton and, yes, Chelsea.

Chelsea’s loss would have been even higher without the

benefit of £49 million profit on player sales, which will certainly be one of

the highest in the Premier League in 2015/16, if not the highest.

Of course, Chelsea are no strangers to making losses in the

Abramovich era, as they have invested substantially to first build a squad

capable of winning trophies and then to keep them at the top of the pile.

Since the Russian acquired the club in June 2003, it has

reported aggregate losses of £753 million, averaging £58 million a season,

though there has been some improvement since the spectacular £140 million loss

in 2005 with Chelsea posting profits in two of the last five years.

The first profit made under the Abramovich ownership was a

small £1 million surplus in 2012, though this did owe a lot to £18 million

profit arising from the cancellation of preference shares previously owned by

BSkyB, while they were also profitable in 2014.

Chairman Bruce Buck has consistently maintained that the

club’s objective is sustainability: “It has long been our aim for the business

to be stable independent of the team’s results and we continue to reinforce

that.”

Chelsea’s figures have consistently suffered from so-called

exceptional items, which have increased costs by an amazing £202 million since

2005.

Leading the way are two early terminations of shirt

sponsorship agreements £93 million and money paid as compensation paid to

dismissed managers £69 million, though the list also includes impairment of

player registrations £28 million, tax on image rights £6 million, impairment of

other fixed assets £5 million and loss on disposal of investments £1 million.

On the bright side, Chelsea appear to be learning from their

mistakes, as the recent pay-off to Mourinho and his coaching team of £8 million

was around a third of the £23 million it cost in 2008.

It is not clear whether the £5 million reportedly paid to

former club doctor Eva Carneiro following an employment tribunal was included

in this year’s accounts or will only be booked next year.

However, it is profit from player sales that is having an

increasing influence on Chelsea’s figures. In the nine years between 2005 and

2013, Chelsea averaged £13 million profit from selling players, but this has

shot up to an average of £52 million in the three years since then.

Last year included the eye-catching £25 million sale of

Ramires to China, while previous seasons featured some other big money moves:

David Luiz (PSG) £40 million, Juan Mata (Manchester United) £32 million, Romelu

Lukaku (Everton) £28 million, André Schürrle (Wolfsburg) £22 million and Kevin

De Bruyne (Wolfsburg) £17 million.

It is notable how much more money Chelsea make from player

sales than their direct rivals, e.g. over the last three seasons Chelsea earned

£155 million, compared to just £38 million at Arsenal, £35 million at

Manchester City and £21 million at Manchester United. Although Tottenham,

Liverpool and Southampton also generate substantial sums from transfers, this

is more understandable, given their revenue shortfalls.

"Put on your dancing shoes"

Next year’s accounts will be more of the same following the £60

million sale of Oscar to Shanghai SIPG. This trend of players making lucrative

moves to China has clearly benefited the club financially, but it has not met

with Conte’s full approval, “We are talking about an amount of money which is

not right”, though fans of other clubs could be forgiven for thinking that this

is a bit rich, coming from a Chelsea manager.

Indeed, led by Marina Granovskaia, one of Abramovich’s

closest associates, Chelsea have perfected a model whereby they consistently

make money from player sales. As well as the big ticket deals already

mentioned, Chelsea have also made extensive use of the loan system with an

incredible 35 players currently listed as being out on loan (though I may well have lost count).

Although the club argues that this strategy is simply aimed

at giving players experience, it is difficult not to believe that this is

primarily a money making exercise. Given that very few of these players have

succeeded in establishing themselves in Chelsea’s first team, it would appear

that the objective is to develop players for future (profitable) sales, while

effectively placing them in the shop window.

"Oh, sit down, sit down next to me"

The most recent example is Patrick Bamford, signed for £1.5

million in 2012, and sold to Middlesbrough this month for a fee of £6 million,

potentially rising to £10 million with add-ons, even though he never appeared

for Chelsea’s first team. During the last five years the England U21

international has been loaned out no fewer than six times.

From a financial perspective, this is a smart move that has

helped Chelsea meet the Financial Fair Play (FFP) regulations, though the moral

counterpoint was delivered by FIFA President Gianni Infantino, “It doesn’t feel

right for a club to just hoard the best young players and then to park them

left and right. It’s not good for the development of the player.”

However, even though some might complain that this policy smacks

of treating players like commodities (“buy low, sell high”), not to mention

ensuring that rival clubs cannot access promising talent, there are (currently)

no rules against it and other clubs, such as Udinese, have operated in a

similar way for many years without sanctions.

To get an idea of underlying profitability and how much cash

is generated, football clubs often look at EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest,

Depreciation and Amortisation), as this metric strips out player trading and

non-cash items.

In Chelsea’s case this highlights their recent improvement,

as it is has been positive for the last four years, rising from £16 million in

2015 to £35 million in 2016, though still lower than the £51 million peak in

2014.

However, to place that into context, this is way behind

Manchester United £192 million, Manchester City £109 million and Arsenal £82

million. United’s amazing ability to generate cash means that their EBITDA (“cash

profit”) is more than five times as much as Chelsea and helps explain the

Blues’ focus on player sales.

Chelsea have increased their revenue by 29% (£73 million) in

the last three years from £256 million to £329 million. The growth is split

pretty evenly between broadcasting income, which has increased 36% (£38

million) from £105 million to £143 million, thanks to new TV deals in both the

Premier League and the Champions League; and commercial income, which has

nearly gone up by nearly 50% from £80 million to £117 million.

Match day receipts have actually fallen slightly from £71

million to £70 million, which underlines why Chelsea are planning to expand

their stadium.

Although Chelsea’s £15 million (5%) revenue growth in

2015/16 took their revenue to a record level, it was not that good compared to

their major rivals. Admittedly, Manchester United’s £120 million (30%) growth

was influenced by their return to the Champions League, but the growth at

Manchester City £40 million (11%) and Arsenal £21 million (6%) was also higher

than Chelsea.

That said, Chelsea’s revenue should grow in 2016/17, despite

a £60 million reduction from the lack of European competition, as they will

benefit from the new Premier League TV deal including a higher league position

(+£70 million) plus a new commercial deal with Carabao (+£10 million). That

should mean a net £20 million increase to around £350 million.

Furthermore, 2017/18 will be boosted by the £30 million

increment from the Nike kit deal. On the relatively safe assumption that Chelsea

qualify for the Champions League, the 2017/18 figures should be close to £450

million.

As it stands, Chelsea’s revenue of £329 million was the

fourth highest in England in 2015/16, though nearly £200 million lower than United’s

£515 million. They were also a fair way behind Manchester City £392 million,

but quite close to Arsenal £351 million.

Liverpool were within striking distance at £302 million, but

there was a significant gap to the remaining Premier League clubs: Tottenham

Hotspur £209 million, West Ham £144 million and Leicester City £129 million.

Chelsea remained in eighth place in the Deloitte 2016 Money

League, only behind Manchester United, Real Madrid, Barcelona, Bayern Munich,

Manchester City, Paris Saint-Germain and Arsenal. This is obviously excellent,

but they face three major challenges here (in common with other English clubs):

- The leading clubs continue to grow their revenue apace, e.g. Real Madrid and Barcelona have reportedly agreed massive new kit supplier deals worth north of £100 million a season.

- The weakening of the Pound since the Brexit vote means that continental clubs will earn much more in Sterling terms, e.g. the latest Money League was converted at €1.3371, while the current rate has slumped to around €1.17. At that rate, the €620 million earned by Real Madrid and Barcelona would be equivalent to £530 million, taking them above Manchester United.

- The Money League highlights the increasingly competitive nature of England’s top flight with no fewer than 12 Premier League clubs in the top 30 – even before the lucrative new TV deal.

Eagle-eyed observers will have noticed that the Money League

figure for Chelsea’s revenue of £335 million is £6 million higher than the £329

million reported by the football club. This is because they have used the

figure from the holding company, Fordstam Limited.

Although this company has not yet published its 2016

accounts, the £319.5 million reported in 2015 is exactly the same as the figure

in last year’s Money League. The difference is entirely in commercial income.

If we compare Chelsea’s revenue to that of the other nine

clubs in the Money League top ten, we can immediately see where their largest

problem lies, namely commercial income, where Chelsea are substantially lower

than their rivals that have traditionally been more successful in monetising

their brand: Manchester United £150 million, Bayern Munich £134 million (£244

million minus £113 million), Real Madrid £80 million and Barcelona £99 million.

The £106 million shortfall against PSG is largely due to the French club’s

“innovative” agreement with the Qatar Tourist Authority.

On the plus side, Chelsea look to be fine on broadcasting

and not too bad on match day income, though there is room for improvement in

the latter category.

The growth in broadcasting income in 2015/16 means that this

now accounts for 43% of Chelsea’s total revenue, ahead of commercial income

35%, which has risen from 26% in 2009. As a consequence, the importance of match

day income has diminished from 36% to only 21% in the same period, once again

reiterating the rationale for the planned stadium expansion.

Chelsea’s share of the Premier League television money

dropped £12 million from £99 million to £87 million in 2015/16, largely due to

finishing tenth compared to winning the title the previous season.

Nevertheless, they earned more three clubs finishing above them (Southampton,

West Ham and Stoke City), as the smaller merit payment was more than offset by

higher facility fees for having more games broadcast live.

The mega Premier League TV deal in 2016/17 will deliver even

more money. Based on the contracted 70% increase in the domestic deal and an

estimated 40% increase in the overseas deals, the top four clubs will receive

£150-160 million, while even the bottom club will trouser around £100 million.

Although this is clearly great news for Premier League

clubs, it is somewhat of a double-edged sword for the elite, as it makes it

more difficult (or at the very least more expensive) to persuade the mid-tier

clubs to sell their talent, thus increasing competition

The other main element of broadcasting revenue is European

competition with Chelsea receiving €69 million for reaching the last 16 in the

Champions League, which was €30 million more than reaching the same stage the

previous season, partly influenced by the increase in the 2016 to 2018 cycle,

namely higher prize money plus significant growth in the TV (market) pool,

thanks to BT Sports paying more than Sky/ITV for live games.

In fact, Chelsea actually earned the sixth highest in the

Champions League, more than semi-finalists Bayern Munich, because of how the TV

(market) pool works. Each country’s share of the market pool is based on the

value of the national TV deal, which means that English clubs have prospered

from the huge BT Sports deal, though it should be noted that around half of

this goes into the central pot, so they do not receive the full benefit.

Half of the TV pool then depends on the position that a club

finished in the previous season’s domestic league: the team finishing first

receives 40%, the team finishing second 30%, third 20% and fourth 10%. As

Chelsea won the title in 2014/15, compared to finishing third the year before,

they received a higher percentage in 2015/16 for this element.

The other half of the TV pool depends on a club’s progress

in the current season’s Champions League, which is calculated based on the

number of games played (starting from the group stages). In this way, Manchester

City reaching the semi-final last season adversely impacted Chelsea’s share.

Although some have played down the value of Champions League

qualification in light of the massive new Premier League TV deal, it is evident

that it is still financially beneficial.

It has clearly helped Chelsea, who have earned €253 million

from Europe in the last five seasons, more than any other English club. It has

thus become a major revenue differentiator against their domestic rivals with

Chelsea earning substantially more than them in this period: City €32 million,

Arsenal €77 million, United €95 million, Liverpool €176 million and Tottenham

€212 million.

Commercial revenue rose by 8% (£9 million) to £117 million

in 2015/16, which was a little disappointing, given that this year included the

first year of the five-year shirt sponsorship deal with Yokohama Tyres. The

implication is that some of the commercial deals include success clauses, so

the lower league place and failure to qualify for Europe bit hard.

In fact, since 2014 Chelsea’s commercial growth of £8

million (7%) has been smaller than all their rivals, notably Manchester United

£79 million (42%) and Arsenal £30 million (39%).

Currently, Chelsea’s £117 million is less than half of

United’s astonishing £268 million, £90 million below Manchester City’s £178

million and even behind Liverpool’s £120 million.

However, Chelsea’s commercial revenue will increase substantially

in the next couple of years. First, they agreed a three-year deal worth £10

million a year with Carabao, a Thai energy drink company, to sponsor training

wear from 2016/17.

They then signed “the largest commercial deal in the club’s

history” with Nike, which is worth £60 million a year (15-year deal for £900

million), i.e. twice as much as the current Adidas £30 million contract, from

2017/18.

"Boy from Brazil"

The Adidas deal was due to run to 2023, so the six years

from 2017 would have brought in £180 million, compared to £360 million from

Nike over the same period, meaning a £180 million increase. Although this is

reduced to £113 million after considering the £67 million termination fee, it still

represents a tidy improvement.

In addition, the Yokohama Tyres shirt sponsorship of £40

million a year is worth more than double the £18 million previously paid by

Samsung. All in all, these three kit deals will be worth £110 million per

annum, which is £62 million more than the previous £48 million.

These deals will leave Chelsea only behind Manchester United

for the main shirt sponsorship and kit supplier deals – and it’s difficult to

compete with their massive agreements with Chevrolet £56 million (at the June

2016 USD exchange rate) and Adidas £75 million.

However, the £40 million shirt sponsorship is well ahead of

Arsenal – Emirates £30 million, Liverpool – Standard Chartered £25 million,

Manchester City – Etihad £20 million and Tottenham Hotspur – AIA £16 million.

Similarly, the £60 million Nike kit supplier deal will be

much better than those signed by Arsenal and Liverpool, respectively £30

million (PUMA) and £28 million (Warrior), though these will be up for

renegotiation before Chelsea.

Looking further afield new kit agreements reportedly signed

by Barcelona (Nike) and Real Madrid (Adidas) are worth £125 million and £115

million respectively (at the current exchange rate), so the bar is continually

being raised.

Match day income was £1 million (2%) lower at £70 million,

partly due to only staging two domestic cup games, compared to three the

previous season. This revenue stream peaked at £78 million in 2011/12, thanks

to the victories in the Champions League and the FA Cup.

Chelsea’s match day revenue is at least £30 million lower

than Manchester United and Arsenal, though is still pretty good, considering

that their grounds are much larger.

This is reflected in the average attendances with Chelsea’s

41,500 miles behind United (75,000) and Arsenal (60,000). It is also lower than

Manchester City, Newcastle United, Liverpool and Sunderland.

The reason that Chelsea’s revenue is higher than clubs with

higher attendances is that they earn a healthy £2.8 million a game, compared

to, say, £2.0 million at Liverpool and £1.8 million at Manchester City. This is

partly due to their ticket prices, which, according to the BBC Price of

Football survey, are the third highest in England, only surpassed by Arsenal

and Tottenham.

That said, Chelsea have again held ticket prices at 2011/12 levels, which means that general admission prices have remained unchanged in nine of the past 11 years. In addition, supporters attending away games in the Premier League over the next three seasons will pay no more than £30 a ticket.

Nevertheless, Chelsea’s revenue shortfall compared to

United, Arsenal, Real Madrid and Barcelona helps explain why the club has spent

so much time searching nearby locations for a new stadium.

After a couple of false starts, including possible moves to

Battersea Power Station, Earls Court and White City, the good news is that

planning permission has recently been granted by Hammersmith and Fulham borough

council to build a new 60,000 capacity on the Stamford Bridge site.

This will be a complex build with the plan being to dig down

to lower the arena into the excavated ground, while the club will also need to

demolish Chelsea Village buildings that surround the ground and build walkways over

the two rail lines that flank the stadium.

The assumption is that Abramovich will cover the costs,

which have been estimated at £500 million, though it could be much higher, e.g.

Tottenham’s new stadium will reportedly cost £750 million.

"Hair, he goes, there he goes again"

Chelsea Pitch Owners (CPO) still have to vote on whether to

grant Chelsea a longer lease on Stamford Bridge and to give them permission to

move away temporarily while the new stadium is constructed, but it would be

surprising if they did not give the green light.

The aim is to have the new stadium ready for the 2021/22

season, which would mean Chelsea having to find a temporary home for three

years. The club is in discussions with the Football Association to play at

Wembley (as are Tottenham), but nothing has been decided. This would cost up to

£15 million rent a year, though income might be higher if the crowds increased.

Chelsea have previously highlighted “the need to increase

stadium revenue to remain competitive with our major rivals, this revenue being

especially important under FFP rules.” In particular, the doubling of corporate

seating to 9,000 seats could deliver significant additional revenue with more potentially

coming from naming rights or other sponsorship opportunities.

Wages rose by £7 million (3%) to £222 million, driven by a

massive increase in headcount, up 104 from 681 to 785. Playing staff, managers

and coaches increased by 45 to 137, while administration and commercial staff

were 59 higher at 648. The increase would have been even higher if bonuses had

been paid at the same level as the league-winning season in 2014/15.

As a technical aside, note that these wage figures have been

corrected when they have included exceptional items, e.g. in 2013/14 the

reported staff costs of £190.6 million included a £2.1 million credit for the

release of a provision for compensation for first team management changes, so

the “clean” wage bill was £192.7 million.

Following the revenue growth, the wages to turnover ratio

dropped from 69% to 68%, significantly better than the recent 82% peak in 2010.

Interestingly, since the start of the new Premier League TV deal in 2013/14,

revenue and wages growth is identical at 29%, implying a degree of control.

Nevertheless, Chelsea’s wages to turnover ratio is still the

highest of the elite clubs, with the other members of the “Sky Six” much lower:

Manchester United 45%, Manchester City 50%, Tottenham 51%, Arsenal 56% and

Liverpool 56%.

That said, Chelsea have been overtaken by Manchester United,

whose £232 million wage bill is once again the largest in the top flight.

However Chelsea remain a fair bit higher than Manchester City £198 million and

Arsenal £195 million.

There is then a big gap to the other Premier League clubs

with the nearest challengers being Liverpool £166 million, Tottenham £101

million (both 2014/15 figures) and Everton £84 million.

This reflects Chelsea’s stated strategy: “In order to

attract the talent which will continue to win domestic and European trophies

and therefore drive increases in our revenue streams, the football club

continually invests in the playing staff by way of both transfers and wages.”

In the last three seasons, Chelsea’s wages have increased by

£50 million, which is in line with Manchester United £52 million and Arsenal

£41 million. The anomaly is Manchester City, whose wage bill declined by £39

million in this period, partly due to a group restructure, whereby some staff

are now paid by group companies, which then charge the club for services

provided.

Although there is a natural focus on wages, other expenses

also account for a considerable part of the budget at leading clubs, though

there was an unexplained £11 million reduction at Chelsea in 2015/16 to £71

million.

Other expenses exclude wages, depreciation, player

amortisation and exceptional items. They cover the costs of running the

stadium, staging home games, supporting commercial partnerships, travel,

medical expenses, insurance, retail costs, etc.

This means that Chelsea were also knocked off the top of this

particular league table, with both Manchester clubs now ahead: United £91

million, City £86 million.

Another cost that has had a major impact on Chelsea’s profit

and loss account is player amortisation, reflecting the significant investment

in players. Chelsea’s initial wave of purchases under Abramovich saw player

amortisation shoot up to £83 million in 2005, before falling away to £38

million in 2010 in line with less frenetic transfer activity. As spending

kicked in again, player amortisation has steadily risen back to £71 million in 2016.

The accounting for player trading is horribly technical, but

it is important to grasp how it works to really understand a football club’s

accounts. The fundamental point is that when a club purchases a player the transfer

fee is not fully expensed in the year of purchase, but the cost is written-off

evenly over the length of the player’s contract, e.g. midfield dynamo N’Golo

Kanté was reportedly bought from Leicester City for £32 million on a five-year

deal, so the annual amortisation in the accounts for him is £6.4 million.

This helps explain why clubs like Chelsea can spend so much

and still meet UEFA’s Financial Fair Play targets.

Unsurprisingly, this is one of the highest player

amortisation charges in the Premier League, only surpassed by big spending

Manchester City £94 million and Manchester United £88 million.

The value of Chelsea’s squad on the balance sheet increased

to £241 million in 2016, though this understates how much they would fetch in

the transfer market, not least because homegrown players are ascribed no value

in the books. Chelsea are one of the few clubs to formally acknowledge this

factor in the accounts, as they have valued the playing staff at a cool £399

million.

Chelsea’s activity in the transfer market is interesting.

For the four years up to 2010 Chelsea’s average annual net spend was just £2

million, before rising to £67 million in the four years up to 2014, then

apparently dropping back to £41 million in the last three seasons (excluding

this January transfer window).

However, this is a little misleading, as it is partly a

result of the increased player sales. If we look at gross spend, it tells a

different story with Chelsea averaging around £100 million a season over the

last seven years. Last summer alone they splashed £119 million on recruiting

David Luiz, Michy Batshuayi, N’Golo Kanté and Marco Alonso.

Even so, their total net spend of £123 million in the last

three seasons was comfortably beaten by Manchester City £299 million,

Manchester United £275 million and (less predictably) Arsenal £165 million,

though it was still a fair way above champions Leicester City £84 million.

Chelsea have no financial debt in the football club, as this has all been converted into equity by issuing new shares. That said, the club’s holding company, Fordstam Limited, does have well over £1 billion of debt (£1,097 million as of June 2015) in the form of an interest-free loan from the owner, theoretically repayable on 18 months notice.

There were some minimal contingent liabilities of £2.4

million, reflecting the fact that Chelsea, unlike most football clubs, pay all

their transfer fees upfront, which must be an advantage in negotiations

compared to other clubs that have to pay in stages.

Other clubs have to carry the burden of sizeable debt,

notably Manchester United who still have £490 million of borrowings even after

all the Glazers’ various re-financings and Arsenal, whose £233 million debt

effectively comprises the “mortgage” on the Emirates stadium.

The advantage of having a benefactor like Abramovich is

demonstrated by the annual interest payments at those clubs: £20 million for

United, £13 million for Arsenal. Since 2010 United have paid out more than £400

million in financing costs, while Arsenal have paid £275 million in interest

and loan repayments in that period. That is money that could have been spent on

transfers or player wages – if their owner had acted like Chelsea’s favourite

Russian.

Although Chelsea’s cash flow from operating activities has

turned positive in the last four seasons (after adjusting for non-cash flow

items, such as player amortisation and depreciation, plus working capital

movements), they still require funding from the owner to cover player purchases

and investment in improving facilities at Stamford Bridge and the training

ground at Cobham.

That amounted to £90 million in the last two years: £43

million in 2016 and £47 million in 2015. In fact, since Abramovich acquired the

club, he has put around £1 billion into the club, split between £620 million of

new loans and £350 million of share capital. In that period £685 million of

loans have been converted into share capital, including £12.5 million last

season.

Most of this funding has been seen on the pitch with £753

million (77%) spent on net player recruitment, while another £140 million went

on infrastructure investment. A further £46 million was required to cover

operating losses with £12 million on interest payments, while the cash balance

has increased by £23 million.

Indeed, Chelsea now have healthy cash at bank of £27

million, though this is still a lot lower than United £229 million and Arsenal

£226 million. It’s a different approach: Abramovich puts his money into the

club, especially the team, while United and Arsenal have to rely on cash

generated from their own operating activities – though they do leave an awful

lot of it in their bank account.

Given Chelsea’s several years of heavy financial losses,

many observers had believed that they would fall foul of FFP, but that has not

been the case with the accounts confirming that the club was compliant with

both UEFA FFP and Premier League financial regulations.

The club has taken advantage of some of the allowable

exclusions for UEFA’s break-even analysis, namely youth development,

infrastructure and (for the initial monitoring periods) the wages for players

signed before June 2010.

Even though Chelsea are compliant, it is clear that this

legislation has been at the forefront of the club’s thinking. The accounts

state: “FFP provides a significant challenge. The football club needs to

balance success on the field together with the financial imperatives of this

new regime.”

"Points of Authority"

Specifically, Chelsea will need to consider the Premier

League’s Short Term Cost controls, which restrict the annual player wage cost

increases to £7 million a year for the three years up to 2018/19 – except if

funded by increases in revenue from sources other than Premier League

broadcasting contracts, e.g. gate receipts, commercial income and profits on

player sales.

Sound familiar? That’s pretty much been Chelsea’s strategy

over the last few years.

It obviously helps if you have an owner with pockets as deep

as Abramovich, but that is no longer enough in a football world full of

financial regulations, so Chelsea have had to follow a different path.

It might sound a little strange to say this after Chelsea just announced a

£70 million loss, but there’s no doubt that there are some clever people at

Stamford Bridge, who have found several ways to grow income and thus meet the

demands of FFP. At the same time, they have managed to put together a squad that is not

only challenging for major honours, but is a good bet to win the Premier League for

the second time in three seasons.