It should perhaps be no surprise that Newcastle United find

themselves embroiled in a relegation battle, given that they only avoided this

fate last season after a memorable 2-0 win against West Ham on the final day,

but it still feels wrong that a club of their resources is in such a position.

Just four years ago Alan Pardew guided Newcastle to fifth place

in the Premier League, the highest since the Bobby Robson days, thus qualifying

for the Europa League, where they reached the quarter-finals before being

eliminated by eventual finalists Benfica.

Since those heady days, Newcastle’s ambitions have seemed to

be limited to surviving in the top flight, where they can continue to benefit

from the lucrative Premier League TV deal. This focus on the bottom line was

perhaps best encapsulated after Pardew’s departure, when the board opted to

elevate the assistant manager, John Carver, to the hot seat, where he looked

hopelessly out of his depth.

"Four seasons in one day"

After a few painful months, Carver was replaced by Steve

McClaren, who proved to be another poor choice. He was duly sacked last month

with Rafael Benitez being given the opportunity to keep Newcastle in the

Premier League. Although Rafa is a manager with a fine pedigree, his arrival

might yet prove to be a case of “too little, too late”.

Newcastle had never been relegated from the Premier League

before owner Mike Ashley bought the club in 2007, but they are now facing their

second demotion in eight years. Admittedly, Ashley’s financial support helped

the club bounce back at the first time of asking on the previous occasion in

2010, but the consequences could be severe this time round.

Although Ashley has turned around the club financially, this

is man that clearly favours profit over performance. Given the financial issues

of the past, few would begrudge him running Newcastle United as a business, but

his very prudent approach has gone too far, bringing to mind an old song from The

Clash, “we’re cheapskates, anything will do.” At times it has felt like the

club is little more than a billboard to advertise Ashley’s tawdry Sports Direct

retail empire.

"It's OK Jonjo"

The owner’s nine-year reign has been a fairly disastrous

period that has only succeeded in sucking the joy out of a massive club. By

Ashley’s own words, he has been a failure: “I wanted to help Newcastle, I

wanted to make it better, but I haven’t seemed to have that effect.”

In fairness, Newcastle have belatedly started to splash the

cash, investing nearly £80 million on new signings in the last season, the

second highest net spend in the Premier League behind Manchester City, to

purchase the purchase of Georginio Wijnaldum, Aleksandar Mitrovic, Chancel

Mbemba, Florian Thauvin, Jonjo Shelvey, Andros Townsend and Henri Saivet.

However, they have clearly spent very badly, failing to

address the obvious inadequacies in their defence, leading to an unbalanced

squad that has once again struggled.

Much of the blame for these poor signings could be

attributed to managing director, Lee Charnley, who appears to be a very good

example of the Peter Principle, whereby “managers rise to the level of their

incompetence.”

"A sad lament"

This certainly seemed to be Ashley’s view, when he describe

his job in this way: “I make sure that the football board have the maximum financial

resources and it is their job to get the best pound-for-pound value of those

resources.”

That may be the case, but it is also Ashley’s job to appoint

the right people to run the club. In any case, he has admitted that the

ultimate responsibility for Newcastle’s poor performance stops at “my door”.

Moreover, the club’s strategy of signing players on the

cheap from foreign markets, mainly France, with a view to putting them in the

shop window, then selling them for large profits, has not exactly been a

glittering success. In fact, only two players have commanded transfer fees above

£10 million, namely Yohan Cabaye and Mathieu Debuchy.

The other point worth making about Newcastle’s recent higher

spending is that it has been financed by their Premier League profits, as

opposed to Ashley putting any more money into the club.

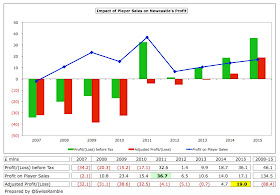

This was highlighted by Newcastle reporting a £17 million increase

in profit before tax in 2014/15 from £19 million to £36 million (£32 million

after a tax charge of £4 million). This is a record high profit for the club,

so no wonder Charnley described the financial results as “positive”.

The main reason for the improvement was a £13 million (17%)

reduction in the wage bill, largely due to “the absence of bonus payments”,

reflecting the feeble displays on the pitch. Other expenses were also cut by £3

million (13%) from £24 million to £21 million, but player amortisation rose by

£1 million (5%) from £20 million to £21 million.

Revenue was £1 million lower at £129 million, which Charnley

almost seemed to think was some kind of achievement: “Turnover remained fairly

constant compared to the prior year, falling less than 1% overall.”

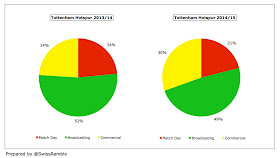

Both broadcasting and commercial income dropped by £1

million, broadcasting by 1% from £78 million to £77 million, commercial by 3%

from £26 million to £25 million. In contrast, match day increased by £1 million

(3%) from £26 million to £27 million.

Profit from player sales rose £3 million (22%) from £14

million to £17 million, mainly due to the sale of Mathieu Debuchy to Arsenal.

Newcastle’s £36 million was actually the second best profit

reported in the Premier League for 2014/15, only surpassed by Liverpool’s £60

million. Making so much money when the team is not up to scratch is not ideal, so

Charnley even seemed apologetic when speaking about these figures, “We

appreciate that, at the present time, football results and not financial

results are what our supporters want to see from us.”

Of course, the Premier League these days is a largely

profitable environment, thanks to the fortuitous combination of increasing TV

deals and Financial Fair Play (FFP) regulations. As a result, fourteen clubs

have so far reported profits in 2014/15 with just five clubs losing money and

two of those (Manchester United and Everton) only lost £4 million.

Newcastle would actually be top of the profitability league

if (once-off) player sales were excluded. Although Newcastle made £17 million

from this activity in 2014/15, Liverpool made £56 million, largely due to the mega

sale of Luis Suarez to Barcelona.

Making money is nothing new for Newcastle with the club’s

stated objective being “to achieve a sustainable financial position, able to

operate without reliance on external bank debt or additional long term

financial support from our owner and meet UEFA’s Financial Fair Play

requirements.”

In fact, this is the fifth consecutive year that Newcastle

have been profitable and they have accumulated total profits of £99 million

since 2011. The first three years of the Ashley era saw losses between 2008 and

2010, but since then the club has been very firmly in the black.

Not only that, but Newcastle have made more money than any

other club in that five-year period with the only other clubs that come close

to them being Tottenham £89 million, boosted by the huge sale of Gareth Bale to

Real Madrid, and Arsenal £85 million, the unofficial poster boy for financial

success in the football world.

Indeed, Newcastle are one of only three Premier League clubs

that have managed to report profits in each of the last five years (Arsenal and

WBA being the other two). It’s little wonder that supporters are enraged by

this level of profit, especially when they compare it with the absolute poverty

of the playing squad.

Part of the improvement in profits is down to the

elimination of exceptional charges. Between 2007 and 2011 the club had to pay

£29 million for what could be loosely described as mismanagement, but nothing

since then.

This included £11 million in pay-offs to former managers

(Glenn Roeder, Kevin Keegan and Sam Allardyce), £12 million in player

impairment (i.e. writing down the value of players), £2 million to former

directors and £3 million for costs relating to aborted financing project and

takeover bids.

Over the years player sales have had a decent impact on

Newcastle’s profits contributing £117 million since 2008, including £85 million

in the last five years alone with Andy Carroll’s move to Liverpool in 2011

being the standout transfer.

Newcastle would have made small losses without this activity

until 2014, when the latest increase in the TV deal meant that the club would

have been profitable even without player sales, especially in 2015 (£19 million).

Given that it can have such a major impact on reported

profits, it is worth exploring how football clubs account for transfers. The

fundamental point is that when a club purchases a player the costs are spread

over a few years, but any profit made from selling players is immediately

booked to the accounts.

So, when a club buys a player, it does not show the full

transfer fee in the accounts in that year, but writes-down the cost (evenly)

over the length of the player’s contract. To illustrate how this works, if

Newcastle paid £15 million for a new player with a five-year contract, the

annual expense would only be £3 million (£15 million divided by 5 years) in

player amortisation (on top of wages).

However, when that player is sold, the club reports the

profit as sales proceeds less any remaining value in the accounts. In our

example, if the player were to be sold three years later for £18 million, the

cash profit would be £3 million (£18 million less £15 million), but the

accounting profit would be much higher at £12 million, as the club would have

already booked £9 million of amortisation (3 years at £3 million).

Cutting through the accounting complexities, basically the

more that a club spends on buying players, the higher its player amortisation. Therefore,

Newcastle’s increased activity in the transfer market has resulted in this expense

rising from £13 million in 2013 to £20 million in 2015. It should be even

higher next year, as this figure does not reflect this season’s spending spree.

Nevertheless, Newcastle’s player amortisation of £20 million

is one of the smallest in the Premier League, though it should also be

acknowledged that Newcastle do tend to sign players on long-term contracts,

which reduces the annual amortisation charge.

It is way behind the really big spenders like Manchester

United, whose massive outlay under Moyes and van Gaal has driven their annual

expense up to £100 million, Manchester City £70 million and Chelsea £69

million, but perhaps more relevantly it is also lower than the likes of

Southampton £30 million and Sunderland £27 million.

The other side of the player trading coin is player values.

Given the ever higher transfer fees, most clubs have reported increases in

player values in recent years, but this has not really been the case at Newcastle.

The 2015 “assets” of £47 million are lower than the £55

million high in 2013 and only just above the £44 million reported in 2009,

though this figure should rise significantly next year.

As a result of all the somewhat confusing accounting

treatment, clubs often look at EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest, Depreciation

and Amortisation) for a better idea of underlying profitability excluding

player trading.

This highlights the improvement in the profitability of

Newcastle’s core operations, as EBITDA steadily declined from 2006 and was

actually negative in 2009 and 2010, but since then it has been rising and

jumped from £27 million to a solid £43 million in 2014/15 alone.

That is not bad at all, only outpaced by the two Manchester

clubs, United £120 million and City £83 million, Liverpool £73 million, Arsenal

£63 million and Tottenham £48 million. Given that Spurs’ revenue is £67 million

more than Newcastle, the fact that their EBITDA is only £5 million higher

highlights the effectiveness of the Geordies’ cost control – or alternatively

how tight their board has been.

In stark contrast, Newcastle have not done so well with revenue, failing to significantly

grow this under Ashley. Before the big man arrived, Newcastle’s revenue was

£87 million in 2007, which has since increased to £129 million in 2015. On

paper a 48% (£42 million) growth is reasonably impressive, but the devil is in

the detail.

Put bluntly, this increase has been entirely driven by the

centrally negotiated Premier League TV deals, which have helped produce a £51

million growth in broadcasting income in this period. The leaps in revenue in

2008, 2011 and 2014 simply follow the three-year cycle for the Premier League

TV deals (2011 obviously also impacted by the promotion from the Championship).

Both the other revenue streams have actually fallen under

Ashley’s command with match day revenue decreasing 20% (£7 million) from £34

million to £27 million and commercial income dropping 10% (£3 million) from £28

million to £25 million (though this was also impacted by the outsourcing of the

club’s catering operation sin 2009). To be fair, commercial income has grown by

an impressive 81% since the low point in 2012, but it still has not returned to

the pre-Ashley levels.

Given Ashley’s reputation as a smooth business operator,

this is highly embarrassing, especially as a previous set of accounts included

this gem: “Match day and commercial revenue is a key driver, because that’s

where the club can compete with – and outperform – its competitors to enhance

its spending capabilities.”

Newcastle’s under-performance in 2014/15 is particularly

telling, as they are one of only six Premier League clubs whose revenue fell

last season. Granted, there is less chance for clubs to massively grow revenue

in the second year of a TV deal, but it is obviously disappointing when revenue

actually declines.

Nevertheless, Newcastle’s revenue of £129 million is still the

seventh highest in England, which sounds great, but the problem is that it is miles

behind the other leading clubs. To place this into context, they are still

around £250 million below Manchester United (£395 million), £200 million below

Arsenal (£329 million), £170 million below Liverpool (£298 million) and £70

million below Tottenham (£196 million).

This massive financial disparity shows how difficult it is

for Newcastle to challenge at the highest level, however they are still the

“best of the rest”, ahead of Everton £126 million, West Ham £121 million, Aston

Villa £116 million, Southampton £114 million and (most meaningfully) Leicester

City £104 million. In short, Newcastle should be doing much better on the pitch.

Despite the marginal decrease in 2014/15, Newcastle actually

rose two places in the Deloitte Money League to 17th, partly helped by the

strengthening of Sterling against the Euro. Amazingly, they generate more

revenue than famous clubs like (deep breath) Inter, Galatasaray, Napoli,

Valencia, Seville, Hamburg, Stuttgart, Lazio, Fiorentina, Marseille, Lyon,

Ajax, PSV Eindhoven, Porto, Benfica and Celtic.

That’s obviously a fine accomplishment, though not as good

as 2003 when Newcastle were as high as 9th in the Money League. Furthermore, it

merely highlights a new challenge for clubs like Newcastle, as no fewer than 17

Premier League clubs feature in the top 30 clubs worldwide by revenue, thanks

to the TV deal. This means that the mid-tier clubs have more purchasing power

than ever before, so are more competitive as a consequence.

All that lovely Premier League money means that 60% of

Newcastle’s revenue comes from broadcasting with 21% from match day and 19%

from commercial.

Newcastle’s share of the Premier League television money was

virtually unchanged at £78 million in 2014/15, despite smaller merit payments

for finishing five places lower in the league (15th compared to 10th), as this

was offset by being shown live on TV 20 times (compared to 14 the previous

season), which increased the facility fee. This is where Newcastle’s “box

office” (or “soap opera”) reputation helps them financially.

Interestingly, if Newcastle had managed to repeat their feat

of finishing 5th in 2011/12 in the last three seasons, they would have banked

around £30 million more money.

Even though the Premier League deal is the most equitable in

Europe with all other elements distributed equally (the remaining 50% of the

domestic deal, 100% of the overseas deals and central commercial revenue), this

underlines the price of failure.

It highlights the tricky balance between sustainable

spending and investing for success. Spending money is obviously not a

guarantee, but a safety first approach can end up leaving money on the table.

Furthermore, there will be even more money available after

the mega Premier League TV deal starts in 2016/17. My estimates suggest that Newcastle’s

15th place would be worth an additional £37 million under the new contract,

taking their annual payment up to an incredible £115 million. This is based on

the contracted 70% increase in the domestic deal and an assumed 30% increase in

the overseas deals (though this might be a bit conservative, given some of the

deals announced to date).

That is why relegation would be such a big deal for

Newcastle. This has been described by the club as a key risk, namely “team

performance impacts all aspects of the club’s operations, not least the

retention of Premier League status, which is critical to much of the club’s

revenue.”

If they were to drop down, they would get around £38 million

TV money in the Championship, including a £35 million parachute payment and £2

million distribution from the Football League, compared to the estimated £115

million in the Premier League, i.e. a £77 million reduction.

Obviously, this would be considerably higher than those

Championship clubs without parachute payments, as they only receive £5 million,

so Newcastle would almost certainly have the highest revenue in the division (though

their commercial and match day income would also probably fall).

That said, it’s still a considerable reduction in revenue

that would require major cuts in the cost base, so it is worrying to read

reports that the club has not inserted relegation clauses in every player’s

contract that would automatically cut wages in the Championship. Either way,

they would likely still have to sell the club’s better players – if they can

find buyers.

Another point worth noting is that from 2016/17 clubs will

only receive parachute payments for three seasons after relegation, although

the amounts will be higher. My estimate is £75 million, based on the

percentages advised by the Premier League (year 1 – £35 million, year 2 – £28

million and year 3 – £11 million). Up to now, these have been worth £65 million

over four years: year 1 – £25 million, year 2 – £20 million and £10 million in

each of years 3 and 4.

Newcastle’s match day revenue rose slightly by £0.9 million

(3%) from £25.9 million to £26.8 million. The accounts attribute this to “one

additional home cup match this year”, which is puzzling as Newcastle did not

host a single domestic cup tie in 2014/15, compared to one in the FA Cup and

two in the Capital One Cup the previous season.

Their match day revenue is the seventh best in England, but

it is a long way behind Arsenal £100 million, Manchester United £91 million, Chelsea

£71 million, Liverpool £59 million, Manchester City £43 million and Tottenham

£41 million.

This is despite Newcastle having a supporter base that is

the envy of almost every other club with an average attendance of over 50,000

being the third highest in the country, the mismatch with revenue being due to

lower ticket prices and corporate hospitality.

The club has implemented a number of initiatives as a

“commitment to keeping ticket prices affordable for our supporters”, including a

ten-year deal in 2011/12, freezing season ticket prices for the last three

seasons and reducing prices for younger supporters. This is all very admirable,

but Ashley’s detractors would point out that most of the initiatives were only

introduced after attendances fell, as the board attempted to once again fill

the ground.

Either way, since the promotion back to the Premier League

in 2010 attendances have been steadily rising. The loyalty of the fans was

shown by the fact that Newcastle’s crowds were the fourth highest in England

even when they played in the Championship with a 43,000 average, which is an

incredible statistic.

After an impressive 50% increase in 2013/14, thanks to a

“lucrative” new deal with shirt sponsor Wonga and a long-term extension with

kit supplier Puma, commercial income marginally fell in 2014/15 by £0.9 million

(3%) from £25.6 million to £24.9 million, mainly due to once-off income from

hosting the Kings of Leon concert in the prior year.

For a club of Newcastle’s magnitude, their commercial

revenue of £25 million is on the low side, paling into insignificance compared

to the top six clubs: Manchester United £197 million, Manchester City £173 million,

Liverpool £116 million, Chelsea £108 million, Arsenal £103 million and

Tottenham £60 million.

It might be argued that such comparisons are a tad

unrealistic, but it’s a similar story if you lower your sights to the mid-tier

clubs, e.g. Aston Villa £28 million, Everton £26 million.

Not only is commercial income lower than the £28 million

that Ashley inherited eight years ago, but Newcastle are the only top ten

Premier League club not to grow commercially in that period, even though the

club apparently “continues to focus on maximising commercial revenue”.

Before Ashley arrived Newcastle’s commercial income was at a

similar level to Tottenham, but the North London club has grown this revenue

stream by 56% since 2007 while Newcastle have fallen by 10%. In the same period

Aston Villa and Everton have overtaken Newcastle, while Liverpool and Arsenal

have grown by £73 million and £62 million respectively.

In fairness, Newcastle’s £6 million shirt sponsorship with

Wonga is only surpassed by the deals made by the top six clubs, even though the

association with a provider of payday loans at extortionate rates feels

horribly cheap. That said, the disparity is again enormous with Manchester

United earning £47 million a year from their Chevrolet deal and (maybe a better

comparative) Tottenham signing a £16 million agreement with AIA.

Even though the club said that it is working hard to add new

sponsors, it is worth noting that they reduced their commercial staff from 54

to 35 in 2014/15. Moreover, the ubiquitous presence of Sports Direct

advertising surely puts off other potential partners.

The accounts state that “advertising and promotional

services were provided to Sports Direct” free of charge, but note that the club

“anticipates receiving payment for these services in the future”, though

without specifying exactly how much. What we do know is that the club purchased

£2.3 million of goods from Sports Direct last season (down from £2.8 million),

so the deal would have to be higher than that for a net benefit.

The wage bill was massively cut by £13 million (17%) from

£78 million to £65 million, slashing the wages to turnover ratio from 60% to 51%.

This reduction was due to the absence of bonus payments for finishing in the

top ten of the Premier League plus “the cost and timing in the prior year of

some significant changes to the playing and development squad”.

Based on their revenue level, we would expect Newcastle to

have the 7th highest wage bill in the Premier League, but it was in fact the 17th

highest, only ahead of Leicester, Hull City and Burnley. Mike Ashley’s fondness

for a bet is well known, but this could be a gamble too far in the increasingly

cutthroat top tier.

Of course, they are still miles behind the elite clubs, e.g.

Chelsea £216 million, Manchester United £203 million, Manchester City £194

million and Arsenal £192, but they have also been overtaken by the other

so-called mid-tier clubs.

Charnley has observed that “our wage bill for the year to 30

June 2016 will increase by a minimum of just under £9 million as a result of

our activity during this transfer window”, but that would only take them to

mid-table in terms of wages.

While it is praiseworthy to have a such a low wages to

turnover ratio of 51%, this is normally due to high revenue (e.g. this is the reason

for the same 51% ratio at Manchester United and Tottenham), but in Newcastle’s case

this is purely down to cutting costs, so can actually be considered as a bit of

a warning sign. The only club with a lower ratio than Newcastle in 2014/15 was Burnley.

In fact, Newcastle very much went against the wages growth

trend in the Premier League in 2014/15 when they reduced the wage bill. Only

two other clubs did the same (Manchester United and Manchester City were both

5% lower), but Newcastle’s decrease was the largest by some distance with a 17%

cut.

One exception to the wages decrease was the highest paid

director, presumably Lee Charnley, who saw his remuneration jump 40% from £107k to

£150k.

Quite tellingly, Newcastle enjoyed the 5th highest wage bill

in England before Ashley bought the club in 2007, but since then the wage bill

has risen by just £5 million (9%) from £60 million to £65 million.

Every other Premier League club has increased their wages by

significantly more in this period with almost all of them overtaking Newcastle.

As an example, Liverpool’s wage bill has shot up by £88 million (114%),

increasing the gap to Newcastle from £18 million in 2007 to £101 million in

2015. U2 once sang of “running to stand still”, but the Newcastle board has

barely broken into a jog here.

For the initial stage of Ashley’s tenure Newcastle were a selling club, averaging net sales of £11 million in the first four

years, though this did include the relegation to the Championship. In the

following three years, they essentially broke-even, somehow managing to go 18

months without signing a full-time professional player, which is some going

(and the height of optimism) in such a competitive league.

However, there has been a distinct loosening of the purse

stings in the last two seasons with Newcastle averaging net spend of £45

million (gross spend £57 million, sales of just £11 million).

In fact, Newcastle have the third highest net spend of £90

million over the last two years, only surpassed by Manchester City £151 million

and Manchester United £132 million. The problem is that they have been doing it

very poorly, effectively achieving the opposite of getting “bang for their

buck”.

As the club’s accounts so aptly noted, “Identification,

negotiation and successful acquisition of the best players, in what is a highly

competitive market, is one of the most significant and high profile risks

facing the club.”

Net debt has been cut by £14 million from £95 million to £81

million, as cash balances rose from £34 million to £48 million. Gross debt was

unchanged at £129 million, entirely owed to Ashley: £18 million repayable on

demand and £111 million repayable after more than one year. This debt is

interest-free, secured on future broadcasting income and repayable on demand.

Gross debt has therefore been cut by £21 million from the peak

of £150 million, but this is still £52 million higher than the £77 million debt

Ashley inherited in 2007. To be fair, the switch from external bank debt to

owner debt has saved a lot of money in annual interest payments (which were as

high as £8 million in 2008).

"Jackinabox"

In the past, the club has argued that Ashley’s free

advertising is worth less than the savings made from removing the requirement

to pay bank interest, which may well be true, but it’s not an overly compelling

argument, particularly if you work on the principle that an owner should have

the football club’s best interests at heart.

It is also striking that none of the debt has been converted

into equity, as is the case with many other football club owners, e.g. Ellis

Short has capitalised over £100 million of loans at Sunderland, while Randy

Lerner has cancelled repayment of £180 million of loans at Aston Villa.

Newcastle have adopted a policy of paying transfer fees

upfront, rather than spreading payments over a number of years, so they owed other

clubs only £3 million, while other clubs owed Newcastle £22 million. In some

ways, this is an admirably prudent approach, but it does restrict Newcastle’s

ability to spend more on bringing players in.

It should be noted that this season’s binge spending has not

been included in these figures with the club stating that it had committed to a

net outlay of approximately £80 million on additions to the playing squad

subsequent to the balance sheet date.

Newcastle’s gross debt of £129 million was actually the 4th highest

in the Premier League, though considerably below Manchester United, who still

have £444 million of borrowings even after all the Glazers’ various

re-financings, and Arsenal, whose £232 million debt effectively comprises the

“mortgage” on the Emirates stadium. QPR’s debt of £194 million was higher, but

their owners have now converted £180 million into equity.

Newcastle have been pretty good at generating cash in the

last few years with £39 million from operating activities in 2015 alone. After

spending £24 million on the playing squad (net of disposals) and £1 million on

capital expenditure, they managed to produce £14 million of positive net cash

flow.

However, this has all gone on this season’s player

recruitment, so when Ashley was asked how much was left in the bank account, he

responded, “Virtually nothing. They have emptied it.”

The last year that Ashley injected funds was £29 million in

2010, which facilitated promotion back to the Premier League at the first

attempt. Not only has he not put any more money in since then, but the club

actually made an £11 million repayment of Ashley’s loan in 2012.

That said, since Ashley bought the club, he has loaned £129

million, providing the majority of the club’s available cash. A further £60 million

has been generated from operating activities, giving a total of £189 million to

spend.

Around £72 million of that has gone on eliminating bank debt

with a further £11 million in interest payments. Around £47 million has been spent

on net player purchases, but less than £10 million invested in infrastructure,

e.g. the promised new state-of-the-art training facility is still a pipe dream.

Newcastle’s £48 million cash balance was one of the highest

in the Premier League, only behind Arsenal £228 million, Manchester United £156

million and Manchester City £75 million, though, as we have seen, that is no

longer the case.

Even though Ashley has twice tried to sell the club, last

season he said that he would categorically not be sell it until Newcastle won

something. That seems clear enough, but it is difficult to believe that there

isn’t a price that might tempt him.

To use his own words, Ashley is now “wedded” to Newcastle

United, but it does feel like the ultimate marriage of convenience, especially

as he has also lamented his decision to acquire the club: “Do I regret getting

into football? The answer is yes.”

"Eyes wide shut"

However, any prospective purchaser would have to shell out

at least quarter of a billion to cover

Ashley’s costs (original acquisition plus outstanding debt), which does not

exactly make the club an attractive proposition, especially if Newcastle drop

to the Championship.

Last month Ashley said, “To get a football club to be the

best it can be, you have to get the sun, the moons and the stars to align

perfectly”, but that seems to be a fairly obvious attempt to wriggle out of his

responsibilities. He failed to invest in the club when it would have made a

real difference and when he belatedly sanctioned player purchases, the people

that he appointed to execute this decision made a hash of it.

Yes, it is no small achievement to put the club on what

Ashley described as “a very sound financial footing” and supporters only need

to look at Sunderland to see that big spending does not automatically deliver success,

but a club of Newcastle’s resources should really be aiming higher.

"Spanish steps"

The ultimate goal of a football club is not to make profits,

but to challenge for trophies. If that is a bridge too far for Newcastle, they

should be capable of comfortably finishing in the top half of the table, and at

the very least not having to fight against relegation.

When Rafa Benitez was appointed, he spoke of the club’s

prospects with some optimism: “The future is brilliant because you have the

power, the fans, the stadium and very positive things. You have the squad. You

have to adapt a little bit, but there is great potential. This club is so big

that we can improve for sure.”

That’s a rousing vision, but first the club has to avoid the

dreaded drop, not least because there is a risk that Benitez might walk if that

comes to pass. Last time round, Newcastle were immediately promoted, but few

would be confident of a repeat performance with the current squad, whose

commitment has been frequently questioned this season.

To paraphrase Bruce Springsteen, there’s darkness on the edge of Toon.

To paraphrase Bruce Springsteen, there’s darkness on the edge of Toon.