These are tough times for Sunderland. Last season was also

difficult, but finished on a high with an appearance in the Capital One cup

final and the “great escape” as a run of late victories avoided relegation.

However, the club is currently just outside the relegation

zone, leading to the sacking of Gus Poyet. As chairman Ellis Short explained,

“Sadly, we have not made the progress that any of us had hoped for this season

and we find ourselves battling, once again, at the wrong end of the table. We

have therefore made the difficult decision that a change is needed.”

It remains to be seen whether former Dutch national team

manager Dick Advocaat is the right man for the job, but it is clear that the

club is completely focused on retaining its Premier League status, especially

with the blockbuster new television deal on the horizon.

Sunderland’s financials for the 2013/14 season emphasise how

important the club’s top flight status is to its future, as their loss widened

from £13 million to £17 million. Although revenue rose by £29 million (38%) to

a record high of £104 million, this was more than offset by a £26 million

increase in expenses and £6 million lower profit on player sales.

The revenue growth was very largely driven by an additional

£28 million from the new Premier League television deal plus £3 million higher

gate receipts, while the expenses growth came from increases in the wage bill

(£12 million) and transfer costs (£10 million) via player amortisation and

impairment. Profit from player sales fell £6 million from £11 million to £5

million.

Sunderland’s £17 million loss is the second worst announced

to date in the Premier League for 2013/14, only behind big spending Manchester

City’s £23 million. In fact, of the 17 clubs that have so far published their

accounts, only four of them have reported losses with the other 13 making

profits, largely due to more revenue being distributed from the central Premier

League TV deal. Sunderland are the only loss-making club whose results actually

worsened in 2013/14.

Of course, this is nothing new for Sunderland, as the last

time that the club made a profit was way back in 2006. Since then they have

accumulated total losses before tax of £145 million, averaging £18 million a

season.

In fairness, the deficits have improved over the last two

seasons compared to the £32 million loss reported in 2012, though this was

largely due to higher profits from player sales (£11 million in 2013 and £5

million in 2014). This also explains why the loss was “only” £10 million in

2011, as the figures were boosted by £26 million from selling players with

Jordan Henderson moving to Liverpool, Darren Bent to Aston Villa and Kenwyne

Jones to Stoke City.

There has been a clear improvement in money made from this

activity (£38 million in the last four years compared to £11 million in the

previous four years), though this is not a strategic objective according to

chief executive Margaret Byrne, who outlined the club’s thinking a couple of

years ago: “We’ll be reporting another big loss this year. We don’t want to do

that, but we’ve taken a decision not to sell our best players. We had lots of

offers in the summer that would certainly have put us in a much better

position, but Ellis said that we’re not selling them. Of course you could be a

profitable club and sell your best players, but it’s a relegation model. We

want to keep our assets and not sell them.”

The other aspect of player trading that has had a

disproportionate impact on Sunderland’s bottom line is player amortisation,

which is the method that football clubs use to account for transfer fees.

Indeed, the club accounts actually note that “the amortisation of transfer fees

increased the loss.”

This is a little technical, but transfer fees are not fully

expensed in the year a player is purchased, as the cost is written-off evenly

over the length of the player’s contract – even if all the fee is paid upfront.

As an example, Steven Fletcher was bought for £12 million on a four-year deal,

so the annual amortisation in the accounts for him s £3 million for four years.

Essentially high player amortisation is the result of high

spending on player recruitment. Sunderland have spent a fair bit of money

bringing players into the club, which has been reflected in player amortisation

rising from just £2 million in 2006 to £30 million in 2014 (including £3

million of impairment costs).

Not only is this a sizeable part (24%) of Sunderland’s total

expenses of £124 million, but it is also one of the highest in the Premier

League, only surpassed by the really big spenders: Chelsea, Manchester City,

Manchester United, Liverpool and Arsenal (and probably Tottenham when they

publish their accounts).

In fact, if we were to exclude non-cash expenses such as

player amortisation and depreciation, then Sunderland’s financials would look a

lot better. This can be tracked by looking at EBITDA – or Earnings Before

Interest, Tax, Depreciation and Amortisation. On this metric, the club has been

basically breaking even in the last few seasons with EBITDA surging to £13

million in 2014.

So everything is hunky dory then? Not so fast, big boy. As

the famous investor Warren Buffett once memorably cautioned: “References to

EBITDA make us shudder. It makes sense only if you think that capital

expenditure is funded by the tooth fairy.” And that’s the point, as money still

needs to be found for player purchases and investment in other assets (like

stadium and training ground improvements).

Sunderland’s cash flow statement highlights this very

clearly. Although the club’s hefty operating losses are brought into line once

non-cash items like player amortisation and depreciation are added back, that

still does not provide any surplus funds for capital expenditure.

Since 2007 Sunderland have made net cash payments of £144

million on players, invested £10 million in new assets and made £21 million of

interest payments on loans. This has been largely funded by £132 million of

borrowings either from the owner or a bank loan guaranteed by the owner. As

Margaret Byrne put it: “Because we’re not producing profits, every time we buy

a player, Ellis (Short) is virtually buying that player for the club himself.

We’re really lucky to have his backing and support.”

One of Sunderland’s underlying problems is a lack of revenue

growth – except for the centrally negotiated Premier League television deals.

Since the club’s first season back in the Premier League in 2007/08, revenue

has increased by £41 million (64%), but almost all of that (£36 million) has

come from new TV deals, hence the rises in 2011 and 2014. Commercial income and

gate receipts have each only grown by around £2 million (16-17%) in the same

period.

Before the new TV deal in 2013/14, Sunderland’s revenue had

actually declined in the last two seasons from £79.4 million in 2011 to £78.0

million in 2012 and £75.5 million in 2013.

Of course, Sunderland’s revenue did rise by an impressive

£29 million to £104 million in 2013/14, but as that man Buffett said, “A rising

tide floats all boats” and all Premier League clubs have seen similar increases

thanks to the new TV deal. In fact, Sunderland have been overtaken by

Southampton in 2013/14, which should leave the Black Cats in 12th place in

terms of Premier League revenue.

Breaking the £100 million barrier is a fine achievement, but

it still leaves Sunderland a long way behind the “big boys”. Five Premier

League clubs generate more than a quarter of a billion of revenue: Manchester

United £433 million, Manchester City £347 million, Chelsea £320 million,

Arsenal £299 million and Liverpool £256 million. In other words, Manchester

United earn more than four times as much as Sunderland.

Nevertheless, it might come as a surprise that Sunderland’s

revenue is the 27th highest in the world, according to the Deloitte Money

League, with the club only just behind the legendary Benfica. Domestically,

this does not cut much ice, as the huge TV money has propelled 14 Premier

League clubs into the top 30 (with all 20 in the top 40).

The higher Premier League TV deal means that broadcasting

now accounts for 69% of Sunderland’s total revenue, up from 59% the previous

season. Commercial income’s share has fallen from 24% to 16%, while match day

has similarly dropped from 17% to 15%. Put another way, broadcasting revenue of

£72 million is 4.6 times as much as match day income of £16 million.

Broadcasting revenue rose 60% (£27 million) from £45 million

to £72 million, almost entirely down to the Premier League distribution. Most

of this is shared evenly between the 20 clubs, namely 50% of the domestic deal

and 100% of the overseas deals. However, 50% of the domestic deal depends on

other factors: (a) merit payments – 25% depends on where a club finishes in the

league with each place worth around £1.2 million; (b) facility fees – 25% is

based on how many times a club is broadcast live.

So Sunderland have enjoyed the benefit of the 2013/14

increase, but there will be even more money available when the next three-year

Premier League cycle starts in 2016/17 with the recently signed extraordinary

UK deals with Sky and BT producing a further 70% uplift. My estimate is that a

club that finishes 15th in the distribution table (as Sunderland did last

season) would receive around £108 million a season, which would represent an

additional £36 million.

Clearly, Sunderland’s big fear is that they will be

relegated and therefore miss out on this amazing prize. As Ellis Short noted in

the accounts: “The directors consider the major risk of the business to be a

significant period of absence from the Premier League.”

Even though Sunderland would be protected to some extent by

the parachute payment of £24 million that is added to the £1.9 million given to

all Championship clubs from the Football League’s own TV deal, they would still

have to contend with a £46 million cut in TV money. That’s a significant

reduction to absorb, even if their players have a 40% wage reduction clause in

their contracts, as has been widely reported. This disparity will become

absolutely colossal once the new 2016/17 TV deal kicks in, e.g. around £71

million, even with an increase in the parachute payment.

Gate receipts were up a healthy 25% (£3.1 million) from

£12.6 million to £15.8 million, largely due to good cup runs in both domestic

competitions with Sunderland reaching the final of the Capital One Cup and the

quarter-finals of the FA Cup. This was despite freezing or even cutting season

ticket prices for the 2013/14 season.

This still places Sunderland in the lower half of the

Premier League table when it comes to match day income and importantly is

significantly less than the elite clubs, e.g. both Manchester United and

Arsenal earn over £100 million here (or nearly seven times as much as

Sunderland). Realistically, this is always going to be the case, as Sunderland’s

ability to charge higher ticket prices and earn from corporate hospitality is

far lower than major clubs. As Byrne said, “You have to look at the area. A

restaurant in London is more expensive than a restaurant in Sunderland.”

No blame can be attached to Sunderland’s supporters, as

their average attendance of just over 41,000 was the 7th highest in the Premier

League, only behind the usual suspects. Byrne again: “Our attendances have been

steady, we’re still averaging 40,000 a game. We’re way up on other clubs.”

In fact, as at the end of March 2015, the attendances are

actually up 4.5% to nearly 43,000 this season, which is an incredible statistic

considering the quality of football on display.

Commercial revenue fell by 7% (£1.2 million) from £18.0 million to £16.8 million, comprising £8.4 million sponsorship & royalties, £7.5m conference, banqueting & catering and £0.9m other. Even more disappointing is the fact that Sunderland have now been overtaken by rivals Newcastle United, whose commercial income rose from £17.1 million to £25.6 million. Clearly, it is also significantly lower than the top six clubs. For example, Manchester United’s commercial revenue is up to £189 million, more than 11 times as much as Villa, followed by Manchester City £166 million, Chelsea £109 million, Liverpool £104 million, Arsenal £77 million and Tottenham £45 million.

The disparity is most evident when comparing the shirt

sponsorship deals. Sunderland have a deal with Bidvest, one of the largest food

services companies in the world, which is worth £5 million a year and runs

until the end of the 2014/15 season. This looks very low compared to the major

clubs, who continue to increase their deals, e.g. Manchester United and Chelsea

have both announced huge new deals recently, United for £47 million with

Chevrolet and Chelsea for a reported £38-40 million with Yokohama Rubber.

It’s a similar story with Sunderland’s kit supplier, Adidas.

Although this deal is a long-term partnership, extended until the summer of

2020, it’s unlikely to be worth more than £1-2 million a season, compared to,

say, Manchester United’s Adidas deal, which will be worth an astonishing £75

million a year from the 2015/16 season.

In fairness, most clubs outside of the absolute elite have

struggled to secure such massive deals and Sunderland would have to enjoy a

sustained run of success to substantially improve their commercial deals.

After a significant decrease the previous season, the wage

bill rose 20% (£11.7 million) from £57.9 million to £69.5 million on the back

of a substantial rise in headcount from 991 to 1,102 (administration/operations

+71, football +22, match day staff +18). The increase reflected the large

number of players recruited by Paolo Di Canio in his six-month reign, though it

is possible that the wages will come back down in the 2014/15 figures,

following numerous departures in the summer.

It is unclear how much has been included for the pay-outs to

Di Canio (or indeed to Martin O’Neill in the previous season’s accounts, but this

factor has presumably also inflated the reported wage bill.

Despite the higher wage bill, the important wages to

turnover ratio was actually reduced from 77% to 67%, which is the lowest it has

been at Sunderland for some time. Nevertheless, this is still the second worst

in the Premier League (of those clubs that have published their accounts), so

there is still work to do here.

This will be a tough challenge, though it should be noted

that the 2013/14 increase has taken the wage bill above both Everton and Stoke

City. Clearly, Sunderland’s wages are significantly lower than the likes of

Manchester United £215 million, Manchester City £205 million and Chelsea £193

million, but it should be enough for them to be in a comfortable mid-table

position, as opposed to being involved in a relegation battle.

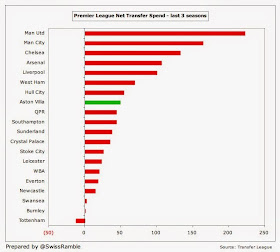

Since they returned to the Premier League in 2007, it feels

like there have been three distinct phases in Sunderland’s transfer activity:

first there was significant net spend of £73 million in the first 3 seasons in

order to strengthen the squad; then the taps were partly turned off with £9

million of net sales in the next two seasons; finally a lot of money was needed

to fund the plans of O’Neill and Di Canio with net spend of £38 million in the

last three seasons.

This recent spending is described by the club as

“significant investment” in the accounts and it does not look too bad compared

to other Premier League clubs in the same period. Obviously, it is far below

the money shelled out by the elite clubs, but it is in the same ball park as

Southampton (£44 million), who have flourished this season.

No, Sunderland’s basic problem is they have bought badly

with a vast quantity of bang average players arriving for inflated fees (Jack

Rodwell, Ricky Alvarez, Jozy Altidore, etc). Former football agent, Robert De

Fanti, had a fairly disastrous record in player recruitment, but this has been

an issue at the Stadium of Light for many years. Current Sporting Director Lee

Congerton will hope to do better than his predecessors, but only time will tell

whether this year’s model will succeed where others have failed.

Debt has risen by £15 million from £79 million to £94

million following a similar increase in the owner loans to £28 million. The

majority of the debt is external with an overdraft of £39 million

(under-written by Ellis Short) and a bank loan of £28 million (secured on the

stadium, interest at LIBOR plus 3%). The bank loan was repayable on August 2014

and has since been refinanced.

Debt has almost doubled from £48 million in 2009 and this is

a sizeable burden for a football club of Sunderland’s size, so it is likely

that much of the extra TV money will be used to reduce this to a more

manageable level. This was more or less confirmed by Byrne: “This TV deal gives

the club a chance to get our books in order.”

More encouragingly, the net amount owed on transfer fees to

other football clubs has significantly reduced from £20.6 million to £8.1

million, as have the contingent liabilities (potential payments that depend on

number of appearances, surviving in Premier League, etc) from £10.1 million to

£8.1 million – and the club states that “some of these are extremely remote”.

If Sunderland do manage to stay up, then they will benefit

from the Premier League’s new Financial Fair Play legislation, which ensures

that the majority of the increased money from the new TV deal remains within

the club and does not simply go to higher player wages (and agents’ fees), as

has invariably been the case with previous increases. Ellis Short was

apparently one of the prime movers behind the rule that states that clubs whose

player wage bill is more than £52 million will only be allowed to increase

their wages by £4 million per season for the next three years.

"You gotta fight for your right to party"

However, this restriction only applies to the income from TV

money, so any additional money from the higher gate receipts, new sponsorship

deals or profits from player sales can still be spent on wages, which does

place more pressure on the club’s commercial arm to deliver the goods.

Something needs to be done to reduce the club’s reliance on

Ellis Short, who has owned the club outright since May 2009, since when he has

injected nearly £130 million of free funding into Sunderland. The accounts show

that he has capitalised around £100 million of loans (£48.5 million in 2009,

£19.0 million in 2010 and £33.4 million in 2013) and provided a further £27.7

million of unsecured, interest free loans with no set repayment date.

This will be largely linked to whether Sunderland achieve

the immediate objective of avoiding relegation. If they do, then the new

Premier League TV money should allow them to reduce their debts, but it will be

up to the club to show that they have learnt from their previous mistakes, in

terms of both player recruitment, which has hit them hard both on and off the

pitch, and managerial upheaval. As a wise person once said, “Just because

everything is different doesn’t mean anything has changed.”