Arsenal’s transfer strategy this summer has left the vast majority of their fans perplexed. While the seemingly interminable Luis Suarez saga has grabbed most of the attention, allied with the failure to secure Gonzalo Higuain when the deal appeared done and dusted, the stark reality is that Arsenal have not bought anybody yet, let alone the marquee signing that the supporters crave. Yes, they have acquired the services of French U20 international, Yaya Sanogo, but he arrived on a free transfer from Auxerre in the French second division..

At the same time, there have been many departures from the

Emirates, including the likes of Gervinho, Mannone, Arshavin, Djourou,

Coquelin, Santos and Chamakh plus a veritable plethora of youth team players.

Although most of these individuals did not feature a great deal in the first

team last year, leading to the unfortunate “deadwood” label, it’s still a fair

amount of experience for the squad to lose with no replacements coming in.

In fairness, Arsenal’s excellent run in the latter stages of

last season was pretty encouraging, though the final Champions League spot was

only secured in a nerve-jangling final game of the season, when Arsenal beat

Newcastle 1-0 away from home (to the apparent astonishment of Lord Sugar, who,

quite brilliantly, imagined a non-existent equalising goal from the Toon Army).

"I wanna dance with Koscielny"

Although Arsenal performed creditably, the fact is that they

never threatened a challenge in the major competitions and were dumped unceremoniously

out of the domestic cups by lower league opposition. Therefore, the need to

strengthen was obvious to all and sundry. A couple of injuries to key players

would highlight the threadbare nature of the squad, which would then have to

rely on youngsters, who may well be talented, but are untested in the heat of

battle, pre-season friendlies not being the best indicator.

As INXS once said, it’s enough to mystify me, especially

given the bullish comments from Ivan Gazidis in June. Ah, those heady days of

(early) summer, when Arsenal’s chief executive boasted, “This year we are

beginning to see something we have been planning for some time, which is the

escalation in our financial firepower.” He continued, “We have a certain amount

of money which we’ve held in reserve. We also have new revenue streams coming

on board and all of these things mean we can do some things which would excite

you.”

But specifically what could this mean? For example, could

Arsenal now pay a £25 million transfer fees and wages of £200,000 for one world

class player? Gazidis pulled no punches, “Of course we could do that. We could

do more than that.”

And he’s not kidding. When you look at the club’s cash

balances – there in black and white in the accounts for all to see – Arsenal’s

spending capacity is evident.

As at the end of the 2011/12 season (the latest year when

football clubs have published their accounts), Arsenal had an incredible £154

million of cash, which is significantly higher than any of their competitors

with Manchester United the closest with £71 million (less than half the

Gunners’ cash pile). An even more amazing statistic is that Arsenal have almost

as much cash as the rest of the Premier League’s other 19 clubs combined (£181

million).

The story is little different on the continent, where

Europe’s leading clubs also retain less cash than Arsenal, preferring to invest

most of their available funds into the squad. As might be expected, the

financially astute Bayern Munich had £95 million, while, perhaps more surprisingly,

Real Madrid had almost as much with £94 million – though both these clubs still

held around £60 million less than Arsenal. Barcelona had much less cash at £31

million, while clubs with smaller revenue generation, like Borussia Dortmund

and Juventus, were barely in the black with £4 million and £1 million

respectively.

Although the club has only really started beating its chest

about its financial strength this year, it has been obvious for a while that

the club could have spent big. As far as back as 2005, former chief executive

Keith Edelman observed, “There are sufficient funds available to the manger for

transfers”, before upping the ante a couple of years later, “We have got plenty

of financial firepower to make the transfers Arsène wants to make. We had over

£70 million of cash at the end of the year and if Arsène wants to spend that

money, we will make it available.” Sound familiar?

Gazidis has been singing from the same song sheet as his

predecessor ever since his arrival, claiming that “The resources are there.

We’ve got a substantial amount of money that we can invest”, before his now

infamous comment about the club keeping its “powder dry” for future player

investment. Although he made this sound like some sort of grand plan from the club,

its cunning appeared to be of the variety that would only have been

recognisable to those who appreciated Baldrick’s schemes in Blackadder.

There has been a steady upward trend over the last few years

in Arsenal’s cash balances, which have grown from £74 million in 2007 to £154

million in 2012. The figure of £123 million announced at the Interims in

November 2012 was lower, but this merely reflects the seasonal nature of cash

flows during the year, e.g. the May balance will always be high following the

influx of money from season ticket renewals, while November is lower as annual

expenses, notably wages, are paid. However, the rising trend can be seen by the

fact that November 2012 figure was £8 million higher than the previous year.

However, this does highlight the fact that not all of

Arsenal’s cash balance is available for transfers. It’s not quite that simple,

due to many factors, including the need to pay those pesky expenses.

Of course, other money will also flow into the club during

the season, such as TV distributions and merchandise sales, though not all of

the reported revenue is necessarily converted into cash, e.g. all of the £55

million from Nike’s initial seven-year kit supply deal from 2004 to 2011 had

been paid by July 2006 (to help with financing the construction of the Emirates

Stadium).

The debt incurred for the new stadium continues to have an

influence over Arsenal’s strategy. Although Gary Neville, amongst others, may

believe that this is no longer an issue, it is clearly a factor with Arsenal’s

gross debt standing at £253 million at the end of 2011/12, comprising long-term

bonds that represent the “mortgage” on the stadium (£225 million) and the

debentures held by supporters (£27 million). In fact, only Manchester United

have a higher debt in the Premier League as a result of the Glazer family’s

highly leveraged takeover.

Although this has come down significantly from the £411

million peak in 2008, it is still a heavy burden, requiring an annual payment

of around £19 million, covering interest and repayment of the principal.

Despite the high interest charges, it is unlikely that

Arsenal will pay off the outstanding debt early. The bonds mature between 2029

and 2031, but if the club were to repay them early, then they would have to pay

off the present value of all the future cash flows, which is greater than the

outstanding debt. In any case, the 2010 accounts clearly stated, “Further

significant falls in debt are unlikely in the foreseeable future. The stadium

finance bonds have a fixed repayment profile over the next 21 years and we

currently expect to make repayments of debt in accordance with that profile.”

Importantly, as part of the bond agreements, Arsenal have to

maintain a debt servicing reserve, which was £24 million in the Interims. In

plain English, this portion of the cash balance is not available to spend on

new players. Similarly, Arsenal also have to maintain a small reserve that is

restricted to use for property development, but that is only £1 million.

Speaking of property development, Arsenal’s interims

mentioned that they would be getting an additional £20 million of cash from

Queensland Road, though this would be “receivable in instalments over a two

year period.” There should also be more money from the two remaining “smaller

projects” on Hornsey Road and Holloway Road, which could be worth another £20

million (estimate), depending on planning permission.

"We have a rather large German"

The amount of cash available is also influenced by

outstanding transfer fees, though this is not a major issue for Arsenal at the

moment: in the Interims Arsenal owed other clubs £31.6 million, but were in

turn owed £31.4 million by other clubs, so this basically netted out.

In addition, the club has so-called contingent liabilities,

where payments are made to a player’s former club based on certain conditions

being met, e.g. number of first team appearances, trophies won, international

caps, etc. These amounted to £7.8 million in the Interims, but are by no means

certain to be paid – that’s why they are described as “contingent”.

Finally, at least in terms of transfer activity, we would

have to add in the net funds from the last two windows, but again this is not a

particularly large factor. This summer, Arsenal have raised around £10 million

from the sales of Gervinho to Roma and Vito Mannone to Sunderland, but they

paid out £8 million to Malaga in January for Nacho Monreal, producing a

positive net impact of £2 million.

The new £150 million commercial deal with Emirates (shirt

sponsorship and stadium naming rights) will have an impact, even though it does

not commence until 2014, with talk of up to £30 million being frontloaded.

Indeed, Gazidis explicitly stated, “We’ll have additional money this financial

year, which will be available to invest in the summer.”

He added, “The deal is all about football, it’s all about

giving us the resources to be able to invest in what we put on to the field for

our fans.” To which, the response that comes to mind is “actions speak louder

than words”.

Gazidis also said, “Our revenues will grow to put us into

the top five revenue clubs in the world”, which was somewhat confusing, given

that Arsenal have been fifth highest in the Deloitte Money League in four out

of the last six years, ever since the move to the Emirates stadium. They were

overtaken by Chelsea last season, mainly due to their fellow Londoners’

Champions League triumph, i.e. a direct result of success on the pitch.

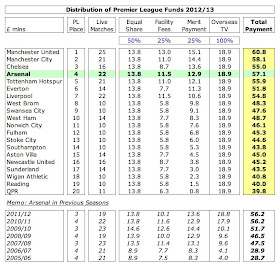

In truth, Arsenal have benefited from higher revenues than

the vast majority of other clubs for many years. Their £235 million turnover

was the third highest in England in 2011/12 and is likely to rise to more than

£300 million in two years time. The aforementioned Emirates sponsorship is more

than £20 million higher than the current deal, as is the new Puma kit 2014

supply deal (widely reported, though not yet officially confirmed), while the

astounding new Premier League 2013/14 TV deal should generate at least £30

million more for a top four club.

In addition, most transfers are funded by stage payments, so

Arsenal would not necessarily need to find all the cash upfront – though other

clubs, aware of the North Londoners’ resources, may insist on most being paid

immediately. In that sense, Arsenal are victims of their own financial success.

Furthermore, Arsenal could always “speculate to accumulate”

by taking on some additional short-term borrowing, which should be no problem,

given the strength of the balance sheet and future cash flows. I’m not saying

that this would be advisable (or even necessary), but it would be a

possibility.

So, what is the magic figure Arsenal have as a transfer fund? Given all of the variables described above, it's safest to quote David Bowie, "It ain't easy", when trying to pin this down, but the oft-quoted £70 million is a reasonable estimate. If funds from property development and future commercial deals are also made available, then it could be as high as £100 million.

So, what is the magic figure Arsenal have as a transfer fund? Given all of the variables described above, it's safest to quote David Bowie, "It ain't easy", when trying to pin this down, but the oft-quoted £70 million is a reasonable estimate. If funds from property development and future commercial deals are also made available, then it could be as high as £100 million.

Arsenal have long been considered the poster child for

financial success, consistently reporting large profits. Not only did they

register the highest profit before tax (£37 million) in the Premier League in

2011/12, but they have also made an incredible £190 million of profits in the

last five years. In fact, the last time that the club made a loss was a decade

ago in 2002. This is virtually unparalleled in the cutthroat world of

professional football.

However, the headline figures do not tell the whole story,

as much of this excellent performance has been down to profits from player

sales (e.g. £65 million in 2011/12) and property development (e.g. £13 million

in 2010/11). Excluding those once-off factors would mean that Arsenal actually

made losses in the last two years: £4 million in 2010/11 and an apparently

worrying £31 million in 2011/12.

In fact, the operating profit from the football business has

been steadily declining since 2009 with the club actually reporting an

operating loss of £16 million last season.

So that explains Arsenal’s reluctance to splash the cash?

Not so fast, big boy, there’s another layer of complexity to

add here, as the accounting profit includes non-cash items, such as player

amortisation, depreciation and impairment of player values. Without wishing to

get overly technical, we need to add these back to the operating profit and

then make an adjustment for working capital movements to get the cash profit.

Once we do that, Arsenal’s cash flow from operating

activities was an impressive £28 million in 2011/12, a figure that was only

bettered by two clubs in the Premier League. The problem is that Arsenal have

spent very little of this on improving their squad: that season the net

expenditure on player purchases was just £2 million – with only four clubs

spending less than the Gunners.

Most of the available funds instead went towards financing

the Emirates Stadium: £13 interest and £6 million on debt repayments. A further

£9 million was invested in fixed assets for enhancements to Club Level, more

“Arsenalisation” of the stadium and new medical facilities and pitches at the

London Colney training ground.

Since 2007 Arsenal have generated a very healthy £376

million operating cash flow. Although they had a small negative cash flow of £7

million in 2011/12, this followed many years of positive cash flow, e.g.

2010/11 £33 million, 2009/10 £28 million, 2008/09 £6 million, 2007/08 £19

million and 2006/07 £38 million.

However, it’s instructive how Arsenal have used this spare

cash. They have spent £71 million on capital expenditure, £110 million on loan

interest and £64 million on net debt repayments. Astonishingly, only 1% (one

per cent) of the available cash flow has been spent in the transfer market.

Although Arsenal have laid out a fair bit of cash on buying players in the last

couple of seasons (over £100 million), this has been more than compensated by

big money sales, leaving a negative net spend.

The other notable “use” of cash in that period is, er,

nothing, as cash balances have risen by £118 million.

That begs the rather obvious question: why not spend the

cash? There’s no one magic answer to this, but let’s take a look at the usual

arguments:

(a) Impact of new signings on the wage bill

One point that people often raise when discussing the

transfer fund is that it would also have to fund a new signing’s wages, so if

the club bought a player for £25 million on a five-year contract at £100,000 a

week, that would represent a commitment of £50 million. That is undoubtedly

true, but it is a little disingenuous, as it ignores the fact that this could

be at least partially offset by the departure of existing players. This is

particularly true this summer, when Arsenal have offloaded so many players.

There is no doubt that the rising wage bill has been a cause

for concern at Arsenal. Since 2009 wages have grown by 38% to £143 million,

while revenue has only increased by 5% in the same period – though this is

where the commercial department could be justifiably criticised for their

failure to add secondary sponsors. The wage bill will have increased again in

2012/13 following revised contracts for the “Brit Pack” (Wilshere, Walcott,

Gibbs, Oxlade-Chamberlain, Ramsey and Jenkinson) to over £150 million.

On the other hand, there will be plenty of room going

forward, as the growth in revenue to £300 million implies a sustainable wage

bill of £180 million (representing a safe 60% wages to turnover ratio). To

place that into context, Chelsea’s current wage bill is £176 million, while

Manchester United’s is £162 million, leaving only Manchester City out of sight

at £202 million.

However, these clubs might be impacted by the new Premier

League regulations, which have restricted the amount of money clubs can spend

from the new TV deal on wages. Specifically, clubs whose total wage bill is

more than £52 million will only be allowed to increase their wages by £4

million per season for the next three years. However this restriction only

applies to the income from TV money, so Arsenal’s additional money from the new

sponsorship deals can still be spent on wages.

(b) Cover a potential failure to qualify for the Champions

League

Many have speculated that Arsenal may be holding cash back

as a “rainy day” fund to cover a revenue shortfall from any failure to qualify

for the Champions League. This has been a lucrative source of funds for

Arsenal, who earned €31 million in 2012/13 from the TV distribution alone, but

Gazidis himself has quashed this theory many times, most recently in June, “The

Champions League qualifier in August won’t affect our plans. It’s never been an

issue when we’ve discussed with players before and it doesn’t affect our

planning.”

(c) Players not available

One of the most fundamental laws of economics is the one

relating to supply and demand and that is relevant here. In other words, it

does not matter if you have money, if there aren’t any quality players to buy.

Gazidis referred to this in his June interview, “It doesn't only require our decision,

it requires the player’s decision and other clubs' decisions, so there is a

market that has to move not just dependant on one party, but dependant on a

number of parties and many of those parties have been in a period of

uncertainty.”

That’s perfectly valid, but has not prevented other clubs

doing business, e.g. Manchester City have already bought Stevan Jovetic,

Fernandinho, Jesus Navas and Alvaro Negredo, while Spurs have acquired

Paulinho, Roberto Soldado and Nacer Chadli.

Less justifiable was Wenger’s complaint that “Some clubs

acted very early so the choices were reduced”, as if the transfer window were

some kind of handicap race and those clubs had been given a head start.

"Cavani - the price is not right"

(d) Valuations are too high

Nobody wants to over-pay, but this is where Arsenal’s

cash-rich position should work to their advantage. There’s no point in having

more money than most other clubs if you don’t make it work for you. As an

analogy, Arsenal may not have quite enough funds to buy in Harrods, but they

could comfortably afford to shop in Waitrose, instead of wasting time haggling

in Aldi.

Some have argued that Gazidis did Arsenal no favours with

his “loadsamoney” speech, but, while this might have weakened the club’s

negotiating stance, it is difficult to believe that executives at other clubs

were not already aware of the Gunners’ financial position.

"Olivier's Army"

(e) Other clubs willing to spend more

Even if Arsenal are well positioned, some clubs still have

more cash to spend. As Gazidis said, “I can’t compete with somebody who has an

unlimited budget.” This echoed the thoughts of former chairman Peter Hill-Wood,

who lamented, “At a certain level, we can’t compete.”

Fair enough, that’s certainly true, especially with the

arrival of Paris Saint-Germain and Monaco on the scene – “more competition

coming from France”, as Wenger drily observed. However, that still does not

explain why the likes of Manchester United, Liverpool and Tottenham have

outspent Arsenal in recent years.

(f) Implications for Financial Fair Play

Under FFFP, UEFA will look at aggregate losses, initially

over two years for the first monitoring period in 2013/14 and then over three

years, so Arsenal’s recent record of large profits would hold them in good

stead, even if they were to temporarily slip into losses before the new revenue

streams came on board. In addition, certain costs such as depreciation on fixed

assets, stadium investment and youth development can be excluded from the

break-even calculation, so this should not be a problem.

In fact, Arsenal hope that UEFA’s FFP regulations will

reward their prudent approach, as these aim to force clubs to live within their

means, thus restricting the ability of benefactor-funded clubs to spend big on

players. Indeed, Gazidis stated that the advent of FFP meant that “football is

moving powerfully in our direction.”

"You make me feel (mighty Monreal)"

(g) Lack of a proper transfer structure

As Monaco’s former chief executive, Tor-Kristian Karlsen,

noted, when commenting on Manchester City and Tottenham’s transfer activity

this summer: “I for one doubt it's a coincidence that the only two teams in the

Premier League with genuine sporting directors (or technical directors or

directors of football, if you like) are the ones who have appeared the most

prepared, structured and with clear strategies in their work in the summer

transfer market.”

If there is a modern, coherent transfer structure in place

at Arsenal, then it seems remarkably well hidden. There may well be a great

deal of activity behind the scenes, but the results speak for themselves.

(h) Will be used to pay dividends to the owner

Although the club’s owner, Stan Kroenke, has no record of

taking dividends from his numerous sports clubs, there is still suspicion among

some sections of the support that his game plan for Arsenal includes this possibility.

When Kroenke was asked at the 2012 Annual General Meeting whether he intended

to take dividends out of Arsenal, his response was hardly unequivocal, as he

merely said that it was a decision for the board.

He added, “I have never said in any meeting that money

wasn't available” and “our goal is to win trophies”, but the feeling remains

that he is content with the status quo of fourth place in the Premier League,

while topping the unofficial table for cash balances.

"Kroenke - the sound of silence"

(i) Makes it easier to sell the club

Having such a high cash balance obviously strengthens the

balance sheet, but the club would arguably fetch a bigger price if it were

successful. Moreover, most investors in football teams do not appear to be

greatly interested in a financial return. Kroenke himself has said, “The reason

I am involved in sport is to win. It's what it's all about. Everything else is

a footnote.”

Indeed, if we look at this purely from the financial

perspective, there is also the opportunity cost of not investing, as this

reduces the chance of success on the pitch. As the presentation of the bond

prospectus in 2006 put it, “the move to the Emirates Stadium should increase

revenues and the ability to sustain a better playing squad – a virtuous

circle.”

Gazidis echoed these thoughts in the summer, “you need the

financial platform in order to create the sporting success, but you need the

sporting success in order to supply the financial platform as well.”

This is why the bond structure includes a Transfer Proceeds

Account, which had the objective of ensuring a high quality playing squad. This

states that 70% of net player sales proceeds must be reinvested in players, but

(crucially) also “other football assets or prepayment of debt”.

Regardless of how that account has been used, Arsenal’s

cautious approach has cost them money. The TV distribution in the Premier

League is relatively egalitarian with each place only worth an additional £0.8

million, but there is a significant upside in the Champions League, best seen

in the 2011/12 season when Arsenal received €28 million for reaching the last

16, while Chelsea earned €60m for winning the competition.

In addition, a relative lack of success on the pitch cannot

have helped Arsenal’s commercial team when they have tried to secure new deals.

We already know that the new shirt sponsorship deal contains a number of

clauses relating to performance, e.g. if Arsenal were to fail to qualify for

the Champions League, the £150 million headline figure (over five years) would

be somewhat less.

"Gazidis - brave boys keep their promises"

The other logical result of Arsenal’s many years of reported

profits is that they are one of the few Premier League clubs that pay

corporation tax: £4.6 million last season (the highest in the league). From a

community aspect, this is a noble thing, but it is money that could have helped

fund a new striker.

This is not a question of whether Arsenal have

under-performed or not. Most neutral observers would agree with Gazidis’

assertion that “We have outperformed our spend, in virtually any metric you can

look at, consistently for the last 15 years.” You can agree with that opinion,

while still being unhappy that the club has not made the best use of its

resources.

Arsenal are by no means a poor side, as they have shown in

some encouraging pre-season displays, including a win against Manchester City,

but they will find it difficult to maintain any sort of title challenge without

strengthening. Obviously, there is still time to make important signings before

the transfer window closes, but that’s not really the point, as the season will

be well underway before Jim White embarrasses himself on Sky Sports News,

including two Champions League qualifiers and the North London derby.

"Oh, Mickey, you're so fine"

No Arsenal supporter in his right mind would want the club

to “do a Leeds”, but they are a considerable distance from that nightmare

scenario. Equally, nobody should expect the promised big spending to guarantee

an end to the recent trophy drought, but it would give the club the best

opportunity to compete for honours, especially at a time when their main rivals

have all gone through various degrees of management upheaval: nothing ventured,

nothing gained.

At the very least, it would provide some substance to

Gazidis’ statements that Arsenal are “extraordinarily ambitious” and “ready to

compete with any club in the world”. As the well-known Arsenal fan, Spike Lee,

once said, it’s time to “Do the right thing.”