Last season was truly memorable for Borussia Dortmund’s many

supporters, as their beloved Schwarzgelben

retained their Bundesliga

title and also secured the first double in the club’s 103-year history by

winning the DFB Cup too. Not only did they avoid the dreaded second season

syndrome, but they actually did so in record-breaking style by setting the

highest points total (81) and the longest unbeaten run in a single season (28

matches). Germany’s leading sports magazine, Kicker,

compared this achievement with Bob Beamon’s “unbelievable” long jump record in

the 1968 Olympics.

They have admirably managed to cope with the loss of key

players each season, so when they sold influential captain Nuri Şahin to Real

Madrid in the summer of 2011, his place in midfield was effectively taken up by

Shinji Kagawa, whose return from injury meant no loss in momentum. Similarly,

when the Japanese international was sold to Manchester United this summer,

Dortmund had already signed his replacement, the highly talented Marco Reus

from Borussia Mönchengladbach.

In the club’s own words, Dortmund’s performance in Europe

was “not as impressive”, as they finished bottom of their Champions League

group behind Arsenal, Marseille and Olympiacos, betrayed by their young team’s

lack of experience at this level. However, they appear to have remedied this

weakness (so far) this season with fine victories over Real Madrid and Ajax

plus much the better of an away draw with Manchester City.

"Götze - super Mario"

All this has been done with Dortmund playing an exciting,

attractive brand of football that has been appreciated by fans everywhere. Under

charismatic manager Jürgen Klopp, this is a side that attacks with pace and

defends with great intensity, proving that teams can win with style.

They have also achieved the seemingly impossible task in

football of combining victories on the pitch with financial success, though it

is equally true that sporting success has helped lead to improved economic

results. In 2011/12 Dortmund’s revenue rose by an imposing 42% to a record €215

million (€189 million excluding player sales), while pre-tax profits surged to

a hefty €37 million. Despite higher bonus payments, the wage bill of less than

€80 million can still be described as “merely average” for the Bundesliga.

These figures provide the most tangible evidence yet that

Dortmund have made a remarkable recovery from their financial difficulties of a

few years ago when they flirted with bankruptcy. In 2002 the club was forced to

sell its famous Westfalenstadion

to a real estate trust, having squandered the funds from its flotation on the

German stock exchange.

Worse was to come as the club splashed out on expensive

signings and high wages, effectively gambling on regular qualification for in

the Champions League to fund this massive spending. When this was not achieved,

they only succeeded in building up huge debts, leaving the club in a

“life-threatening situation”.

"Hummels - Mats entertainment"

The club was saved by the “never say die” spirit of their

supporters, whose “We are Borussia” campaign resulted in Dortmund’s community

of citizens, companies and public authorities combining to help repair the

finances. This included some very understanding creditors and bank managers,

who deferred stadium rent and interest payments until 2007.

Dortmund also had to take out yet another loan to help pay

the players’ salaries, while they were forced to shore up the balance sheet in

2006 with significant capital increases, which enabled the club to obtain a

more manageable debt structure and improved interest rate terms. In particular,

the club took out a 15-year loan of €79 million with Morgan Stanley, which

facilitated the repurchase of the remaining stake in their stadium from the

property fund.

The restructuring process was completed two years later,

when €50 million of cash received after signing a new 12-year marketing

agreement with Sportfive was used to fully repay the Morgan Stanley loan many

years ahead of schedule. The club promised that this move would not only

further reduce its liabilities, but would free up funds to improve its sporting

competitiveness. Two Bundesliga

titles later and it’s fair to say that the club has been true to its word.

"Lewandowski - Pole dance"

Dortmund have learned from their past mistakes (and

excesses) and adopted a far more sustainable business model in the past few

years. They now employ a solid financial strategy, based around the over-riding

principle of “achieving maximum sporting success without taking on more debts.”

The focus is primarily on youth, as explained by managing director Thomas Treß,

“We learned that you have to invest in your youth, to develop your own stars,

adding to your team with young players of potential.”

This investment in relatively cheap, promising young

players, rather than he expensive finished article, has been assisted by the

foundation in 2011 of the BVB Academy, a modern training centre to develop

players between the ages of 19 and 23. Dortmund’s youth academy has been a

veritable production line for the first team, turning out talent like Mario

Götze, Marcel Schmelzer and Kevin Großkreutz, while other youngsters like Mats Hummels and Sven Bender have been further developed at Dortmund. Most

of these players have signed long-term contracts with Dortmund until 2016 or

2017.

Bayern Munich’s outspoken president Uli Hoeneß took a pot

shot at his rivals’ approach, “They had to do it that way, because they don’t

have the money.” Well, exactly. Very few clubs have the financial power of

Bayern, but it is surely better to make your suit from the cloth available,

rather than spend money you don’t have on a fancy new outfit that falls apart a

couple of years later.

Dortmund’s revised, more sensible approach has been epitomised by

their dealings in the transfer market. In the five years leading up to the

fateful 2004/05 season, the club’s net spend was a chunky €97 million, before

their debt problems forced them to offload players, generating surpluses over

the next three years, followed by very modest spend, so that “transfer income

and expenses are balanced.” Over the last nine years, the club had net sales proceeds

of €5 million – a stark contrast to their extravagant era.

Under sporting director Michael Zorc, Dortmund’s scouting

has been focused on “value development”, so that “transfers should create

substantial earnings potential”, as well as “sustainable sporting

competitiveness”. This means that the young talent is likely to leave “to

secure large transfer income”, though the club acknowledges that this strategy

creates a conflict between financial considerations and sporting criteria. This

can lead to a lack of squad depth, hence the uncertain start to this season in

the Bundesliga.

In fact, over the last three seasons no fewer than nine

clubs in Germany’s top flight have spent more than Dortmund’s net €2 million.

In fairness, very few Bundesliga

clubs spend big on transfers with the obvious exception being Bayern Munich,

who spent €116 million in the same period. Dortmund’s chairman, Hans-Joachim

Watzke, accepted this discrepancy, “I must point out that we continue to

operate in different spheres. Bayern spent €70 million this year, including €40

million on Javi Martinez.”

Thomas Treß added, “We are not able to compete in the

European soccer market with British or Spanish clubs in respect of transfer pricing.”

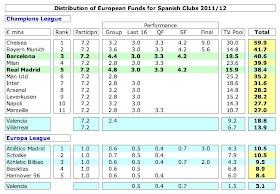

That’s true, but you can also add a few more countries to that list, as can be

seen by the above graph, which highlights the massive difference with other

leading Europe clubs. At one end of the spectrum, we have Dortmund with €2

million; at the other end, three clubs, fueled by oil-rich owners, have

splashed out around a quarter of a billion pounds: Chelsea, Manchester City and

Paris Saint-Germain.

This summer saw a slight change of emphasis with the €17

million capture of Marco Reus, though even this was compensated by the €16

million received for Kagawa. Bayern’s former sporting director, Christian

Nerlinger, conceded, “With this transfer they have established themselves as a

major rival for the championship.” Dortmund claimed that this signing demonstrated

that they were “the team to be for young, ambitious Bundesliga players”, though in fairness

there were special circumstances here, as Reus grew up as a Dortmund fan and

his parents live in the area.

Nevertheless, the suspicion remains that if they receive the

right offer, Dortmund will continue to sell their best players, such as the

prolific forward Robert Lewandowski. Watzke recently denied this, “We won’t

give up Robert for any money in the world. We don’t want to open a bank”, but

few would be surprised if the Polish international were to leave next summer.

Indeed, player sales contributed nearly half (€17 million)

of Dortmund’s very impressive 2011/12 pre-tax profits of €37 million, which

were €27 million higher than the previous season’s profits of €10 million.

After tax was taken into consideration, profits increased from €5 million to

€28 million. That was much more than the previous five years when player sales

produced profits on average of less than €5 million a year.

Operating profit grew by €17 million to €24 million, as

revenue grew by an amazing €51 million (37%) from €139 million to €189 million,

more than off-setting increases in the wage bill (£18 million) and other

expenses (€17 million). Other operating income, largely due to payments from

national associations for the release of Dortmund’s players, also improved by

€3 million to €8 million.

As a technical aside, I am using the Deloitte definition of

revenue here in order to facilitate comparisons with other European clubs, so

have excluded transfer income of €26 million. Adding that to my revenue of €189

million gives the €215 million announced by Dortmund. The profit on player

sales of €17 million is then obtained by deducting transfer expenses of €9

million and is largely due to the sales of Kagawa to Manchester United and

Lucas Barrios to the Chinese club Guangzhou.

It is clear that “Borussia has developed itself economically

and on a sporting level continuously over the last few years”, as Watzke put

it. The profits made in the last two seasons represent a spectacular

turnaround, as the club had previously reported losses in five of the last six

years, including €55 million in the annus

horribilis of 2004/05 and €23 million the year after.

In comparison, Bayern Munich, the “alpha male” of the Bundesliga with 22

league titles and four Champions League victories, have made profits 19 years

in a row, consistently bettering Dortmund’s results off the pitch – except last

season, when the Schwarzgelben’s

€9.5 million was slightly higher than the Bavarians’ €8.8 million. Bayern will

also have to go some to match Dortmund’s €37 million in 2011/12.

Dortmund re-entered Deloitte’s Money League in 2010/11 in

16th position with revenue of €139 million, even without the benefit of Champions

League money. Their 2011/12 revenue of €189 million would have placed them

11th, assuming no growth at other clubs.

That is more than respectable, but the problem is that it is

far below the leading clubs, such as Real Madrid €479 million, Barcelona €451

million, Manchester United €367 million and (crucially) Bayern Munich €321

million. The magnitude of Dortmund’s accomplishment in overcoming Real Madrid

last week can be seen by the relative revenue figures last season with Madrid’s

€514 million being nearly three times as much as Dortmund’s record €189

million.

Bayern’s revenue of €321 million is by far the highest in

Germany, giving them a major competitive advantage over their rivals: Schalke

04 €202 million, Dortmund €189 million, Hamburg €129 million, Werder Bremen

€100 million and Stuttgart €96 million (all 2011 figures, except Dortmund

2012). Moreover, only Dortmund have kept pace with Bayern’s insatiable revenue

growth: since 2007, they have both increased revenue by just under €100

million. Schalke also grew revenue by €88 million, but their 2012 figure is

very likely to fall back after the absence of Champions League revenue, which

was worth €40 million in TV distributions alone in 2011.

Even though Dortmund’s revenue has been going great guns,

rising 80% (€84 million), while Bayern’s actually dipped €2 million last

season, the gap between the two clubs is still a mighty €132 million. This is

nonetheless a lot better than the colossal €218 million shortfall in 2010, when

Bayern’s revenue was literally three times as much as Dortmund’s.

Even so, Dortmund’s revenue growth has been hugely

impressive, more than doubling from €90 million five years ago, especially as

it was relatively flat during the three years between 2008 and 2010 at around

the €105 million level. Last season all revenue streams contributed to the €51

million rise to €189 million: TV €28 million (mainly Champions League

participation) to €60 million; commercial €19 million to €97 million; and match

day €4 million to €31 million.

As we can see, the largest revenue category is commercial

income. In fact, in 2010/11 Dortmund had the highest percentage of their total

revenue from commercial (57%) of any Money League club. Although this has

fallen to 51% in 2011/12, mainly due to Champions League money, this is still a

very high proportion for a football club.

To place that into context, it is worth comparing the

revenue mix with Arsenal, where commercial activities contribute only 23% of

total revenue. In contrast, match day is worth 41% at the North London club,

compared to only 17% at Dortmund. Looked at another way, the majority of

Dortmund’s revenue is generated from companies, while fans bear most of the

burden at Arsenal.

In fact, Dortmund’s striking commercial revenue of €97 million

means that they are only behind the four marketing behemoths of the football

world: Real Madrid €187 million, Bayern Munich €178 million, Barcelona €167

million and Manchester United €130 million.

The club’s commercial strategy is to secure long-term

partners, as seen by their agreement with marketing partner Sportfive, who have

signed with the club until 2020, by which time they will have been the club’s

marketing partner for 20 years. All three main sponsorship deals are long-term

in nature: shirt sponsor Evonik, whose agreement has been in place since 2006,

extended from 2013 to 2016; stadium naming rights partner Signal Iduna also

extended from 2016 to 2021; while new kit supplier Puma signed up until 2020.

Another objective is to sign up many secondary sponsors,

known as “champion partners”, and a lengthy list now includes the likes of

Opel, Sparda Bank, Sprehe, Wilo, Brinkhoff’s, Flyer Alarm, Hankook, Yanmar and

West Lotto.

Dortmund have managed to grow all aspects of their

commercial revenue: sponsorship and advertising rose 16% to €58 million, mainly

due to new partners and an increase in the VIP hospitality occupancy rate to

100%; while merchandising and catering was also up an impressive 41% to €37

million.

Over a third of merchandising revenue is now earned through

the online shop, while a fifth fan shop was opened in the city of Dortmund in

September 2011. According to a survey by PR Marketing, die Borussen sold between 250,000 and

500,000 replica shirts in the 2011/12 season with only eight clubs selling

more. Catering revenue also rose 9% to €10 million.

Despite these successes, Dortmund’s commercial income is

still only around 55% of Bayern’s, partly due to the €38 million revenue the

Bavarians earn from the Allianz Arena, though their sponsorship and advertising

is also €23 million higher. Our old friend Uli Hoeneß said that Dortmund would

need to have a more consistent track record of winning trophies if they hoped

to match Bayern’s global appeal, but in truth they’re doing very well compared

to almost every other club on the planet.

Evonik, a chemical company, has increased its shirt

sponsorship to €10 million, according to the Frankfurter

Allgemeine Zeitung, though this is still lower than deals struck by

some other German clubs: Bayern (Deutsche Telekom), Schalke (Gazprom) and

Wolsburg (Volkswagen). It is also a long way behind the mega deals at the likes

of Real Madrid and Barcelona, though it does include hefty add-ons for sporting

success. The Evonik chairman said that he was very pleased with Dortmund as a

partner, due to their large crowds and title wins (“in a very exciting way”).

German clubs have proved very adept at securing valuable

shirt sponsorship deals. Although the total value of such deals is higher in

the Premier League, the average value of each deal is actually higher in the Bundesliga, as it

has two fewer clubs (according to a study by International Marketing Reports).

Signal Iduna, the naming rights partner, has also increased

its annual payment from €4 million to between €4.5 and €5 million after the

deal extension.

Dortmund’s new kit supplier, Puma, is reportedly paying €6-7

million a season from July 2012, replacing Kappa, whose deal was only worth €4

million. Rather wonderfully, the new shirt has the inscription “Echte Liebe” (true

love) on the inside of the collar. That’s good news, but it is still far below

Bayern’s €25 million deal with Adidas (and, for that matter, Real Madrid’s €38

million agreement with the same company).

Paradoxically, BVB are

helped commercially by the weak digital television market, which means

that German clubs are televised more frequently on terrestrial channels than

their counterparts in England, Spain and Italy, thus providing more exposure

for their sponsors. As the old saying goes, it’s an ill wind that blows no

good.

However, this also means that television income is not very

high in Germany, as can be seen from the 2010/11 Money League, where Dortmund

sat in 19th position. Their revenue of €32 million was around one sixth of the

€184 million earned by Barcelona and Real Madrid, who benefit greatly from

their individual domestic deals.

In 2011/12, Dortmund’s TV revenue rose €28 million to €60

million, very largely due to the €25 million from the Champions League with the

remainder coming from the DFB Cup, which they won compared to a second round

exit the previous season.

They received around €28 million from the Bundesliga

distribution, a small increase on the previous season. TV revenue in Germany is

largely divided among clubs via a points system based on their league position

over the past four years, though some money is also allocated per the number of

games televised live.

Performance is weighted in favour of the more recent years,

so last season a factor of 4 was applied to 2011/12, 3 to 2010/11, 2 to 2009/10

and 1 to 2008/09. However, a form of equality is then applied, as the club with

most points from this algorithm only receives twice as much money as the club

that has the lowest number of points. In this way, as top club in 2011/12

Bayern Munich received €24 million for performance (excluding live fees), which

was double the €12 million for last placed Augsburg.

The Bundesliga

recently announced an increase in the value of their TV rights with the

domestic deal for the four years from 2013/14 to 2016/17 rising 52% from €410

million to €628 million and the overseas rights increased by a similar rate to

€72 million. The new total of €700 million will take it ahead of La Liga (€655

million) and Ligue 1

(which actually fell to €642 million). The Bundesliga’s

chief executive, Christian Seifert, was ecstatic, “ We didn’t expect results

like this, it clearly exceeded our expectations”, while Bayern’s chief

executive, Karl-Heinz Rummenigge, described it as “a milestone in the history

of the Bundesliga.”

Nevertheless, the TV rights for German football are still

lower than Serie A

(€944 million) and only half the Premier League deal (€1.4 billion). That is

before the new English deal from 2013/14, which is estimated to be worth at

least €2.2 billion, i.e. three times the “historic” Bundesliga deal.

Dortmund’s share of the TV revenue should rise to around €40

million, but this is still a lot less than the money earned by English clubs.

Last season’s Premier League winners, Manchester City, pocketed €75 million,

while even the bottom club, Wolverhampton Wanderers, received €49 million. The

new Premier League deal is likely to deliver €110-120 million to the leading

English teams.

Once again demonstrating their innovative spirit, Dortmund

were the first German club to offer their own TV package, BVBtotal!, in January

2011, run jointly with Deutsche Telekom.

Dortmund’s allocation from the Champions League was worth

€25.4 million in 2011/12, considerably more than the €4.5 million they received

from the Europa League the previous season, even though they went out at the

group stage. However, this was still a lot less than the €42 million Bayern

received for reaching the final.

Interestingly, Dortmund (€17 million) still received more

than Bayern (€14.8 million) from the TV (market) pool, due to the methodology

used to allocate this element, which is as follows: (a) half depends on the

progress in the current season’s Champions League, based on the number of games

played; (b) half depends on the position that the club finished in the previous

season’s domestic league. As three German clubs reached the group stage this

season, the split will be: Dortmund 45%, Bayern 35% and Schalke 20%. The Champions League will be worth even more, as the overall prize money for the 2012 to 2015 three-year cycle has increased by 22%, but it will be higher for German clubs, as their TV deals have risen considerably, thus boosting their market pool.

"Grosskreutz - we need to talk about Kevin"

The Europa League is much less lucrative, though German

clubs benefit from relatively high TV deals, so last season Schalke earned the

same (€10.5 million) as the winners Atlético Madrid, even though they were

eliminated in the quarter-finals.

Therefore, Dortmund will be gratified that Germany’s number

of places in the Champions League has increased from 3 to 4 (at the expense of

Italy), due to the improving UEFA coefficients. However, this might prove to be

a double-edged sword, as it could mean that Germany’s TV pool has to be shared

between more clubs.

European money has clearly made a substantial difference to

Dortmund’s revenue, but Watzke has claimed that the club is not economically

dependent on Champions League money and they could survive three seasons without

it, thanks to their long-term sponsorship contracts – though they would have to

make cuts.

Last season Dortmund’s incredible average attendance of

80,500 was the highest in Europe, ahead of Barcelona 79,600 and Manchester

United 75,400. This was easily the largest average in Germany with the next

highest teams being Bayern 69,000 and Schalke 61,200. The Dortmund fans’

interest shows no sign of slowing down, as they have just established a new Bundesliga record

for season tickets for 2012/13 at a mighty 54,000 – and that was capped to

ensure an adequate supply of tickets on the day of the match.

It is therefore a little perplexing to see that Dortmund

have one of lowest match day revenues in the Money League with only €28 million

in 2010/11 (€31 million in 2011/12), while the likes of Real Madrid, Barcelona,

Manchester United and Arsenal all collect more than €100 million. There are two

obvious reasons for this huge discrepancy: less matches and low ticket prices.

There are two fewer home games every season in the

Bundesliga, while last season Dortmund only played three Champions League home

games, bringing in €4.4 million, and one in the DFB Cup. This resulted in a

total of 21 home games compared to 28-29 for the leading English and Spanish

clubs.

Dortmund’s high attendances (and small match day revenue)

can be partially attributed to the large number of standing places for which

season tickets are priced as low as €187 (€109 for youths). Nearly 25,000 of

these can be found on the famous Südtribüne

terrace, known as the “Yellow Wall”, which is the largest standing area in

European football and provides each home game with an intensely passionate

atmosphere. Occasionally, that enthusiasm can go too far, such as the

hooliganism seen at the recent Schalke derby when there were 200 arrests and

water cannon had to be used.

It is surely no coincidence that the Bundesliga has the lowest ticket prices

of Europe’s five major leagues and consequently the highest attendances. This

is an important part of football culture in Germany, as seen recently when

Dortmund fans staged a protest against Hamburg’s steep prices for away standing

tickets, leaving their block after 10 minutes. Klopp gave them his support,

“The league needs to think just how far they want to push prices.”

There are no such problems in Dortmund’s imposing stadium,

now officially named Signal Iduna Park, which is the largest football ground in

Germany and the sixth largest in Europe. This is obviously an extremely

valuable asset that can also be used to host international matches, when the

capacity is reduced to 67,000 by converting the standing areas to seats. The

Times described it as the “most beautiful stadium in the world”, writing,

“Every Champions League final should be held in Dortmund. The place was built

for football and its fans.”

Even though the wage bill has risen by 67% (€32 million)

since 2010 to stand at €80 million, this is still very much under control, as

revenue has grown at an even faster rate of 80% (€84 million). In fact, the

important wages to turnover ratio has actually fallen to a very creditable 42%

from the peak of 48% in 2009, which is even better than the 50% targeted by the

Bundesliga.

The €18 million increase in the total wage bill in 2011/12

was largely due to sporting success, namely higher performance-related bonus

payments, though there was also a rise in administration staff. Treß emphasised

that the club had a “very flexible cost structure”, so any lessening in

performance on the pitch should mean a smaller wage bill. The wage bill is not

analysed in the accounts, but the cost of the football squad has been estimated

at €60 million.

Even after this growth, Dortmund’s total wage bill of €80

million is still only about half of Bayern’s €158 million, though the gap has

come down a fair but from 2010 when it was as high as €118 million. In fairness

to the Bavarians, their revenue is also substantially higher, but that does not

make it any easier for BVB to compete.

This point is even more relevant on the European stage,

where some of the leading clubs can boast wage bills far higher than any in

Germany, e.g. Barcelona, Real Madrid, Manchester City and Chelsea are all above

€200 million (though the Spanish figures are inflated by other sports). To

provide an English comparison, Dortmund’s wage bill is about the same as

Sunderland, Everton and Fulham, which shows just how extraordinary their

achievements have been.

That said, the price of success is that Dortmund’s wage

structure will come under pressure, as their policy of signing stars to

long-term contracts will mean higher salaries, as seen with Götze’s improved

deal.

Dortmund’s executives have also been handsomely rewarded for

the club’s success with Watzke earning €2.2 million in 2011/12, including a

€1.4 million bonus, and Treß trousering €1.4 million, including an €875,000

bonus.

The other staff cost, player amortisation, is incredibly low

at €8 million, which is a perfect demonstration of Dortmund’s conservative

transfer policy. As a comparison, player amortisation at big spending

Manchester City and Real Madrid is around €100 million, while Bayern book €33

million.

To explain this concept, football clubs do not expense

transfer fees completely in the year of purchase, but treat players as assets.

So the cost of buying players (in accounting terms) is spread over a number of

years by writing-off the transfer fee evenly over the length of the players’

contract via amortisation. As an example, Marco Reus was bought for €17 million

on a five-year deal, meaning the annual amortisation is €3.4 million.

In contrast, other expenses of €74 million seem fairly high,

though this does include €25 million for match operations, €17 million

advertising, €12 million materials (primarily merchandising) and €11 million

administration. Note: I have excluded transfer expenses from my definition.

There is further strong evidence of Dortmund’s financial

recovery with the decrease in net debt (financial liabilities) from €150

million in 2006 to €42 million in 2012, including an €18 million reduction last

season alone. This is made up of €47 million gross debt, largely a state-backed

loan for stadium expansion of €32 million (repayable in 2026) and a €12 million

fixed-interest loan (repayable in 2013), less €5 million cash. The average

weighted interest rate of the long-term liabilities is 5.5%. The club also has

access to an additional €15 million overdraft facility.

In fact, the balance sheet is quite strong with net assets

of €155 million, including €183 million of property assets, namely the stadium,

former offices at “Am

Luftbad” and the training ground at Dortmund-Brackel. In addition,

the club possesses what it describes as “hidden reserves” among the playing

staff, following its policy of recruiting young talent with a lot of potential.

Their value in the books is only €26 million, while their real worth in the

transfer market is considerably higher – €211 million according to the Transfermarkt

website.

Dortmund have generated positive net cash flow for the last

two years: €7.8 million in 2011 and €6.4 million in 2012. As a sign of the

board’s confidence, the club has proposed a dividend for the first time since

it went public in 2000 with a total payment of €3.7 million scheduled to be

discussed at the Annual General Meeting in November.

"Weidenfeller - the Roman empire"

The Bundesliga

itself is in fine shape, as Klopp explained, “We have the most competitive and

the most attractive league in Europe with the best stadiums. The fans are

great.” This is reflected in the situation off the pitch: only the Premier

League (€2.5 billion) has higher revenue than the Bundesliga (€1.7 billion), while the

German league is more profitable at an operating level (€171 million) than its

English counterparts (€75 million) with all other major leagues reporting

losses.

As part of the German rules, clubs have to provide a

balanced budget before each season in order to receive a license, which forces

them to act in a sustainable manner, as seen by an average wages to turnover

ratio of 50% (compared to 70% in the Premier League).

In addition, the “50+1” rule, which dictates that members

must own a minimum of 50% of the shares plus a deciding vote, theoretically

prevents the club being subject to the whims of an individual owner and taking

on excessive debt. This has very largely worked, e.g. debt levels in the Bundesliga are less

than a third of those in the Premier League, but the system is not completely

foolproof, as seen by the problems experienced by Dortmund and Schalke among

others.

A club as well run as Dortmund should be one of the main

beneficiaries of UEFA’s Financial Fair Play (FFP) regulations, which encourage

clubs to live within their means. As Watzke explained, “If FFP is implemented

and rigorously enforced, we have a chance to be one of the strongest teams in

Europe.”

Even the losses made between 2008 and 2010 were within

UEFA’s limits: the allowable losses are an aggregate €45 million for the first

two years (then three years), but this is only €5 million if losses are not

covered by the owners, which might be more relevant here. In any case, they can

exclude certain expenses, including depreciation on tangible fixed assets and

expenditure on youth development and community activities, which I estimate would

be worth around €13-15 million.

Watzke himself has gone further, imploring the regulators to

act tough, “UEFA must find the thin line between sponsorship and excessive

back-door funding – they must show strength to expel big clubs. No tycoon

should be allowed to pump crazy money into a club with sponsorship from five

companies he controls. If that happens, financial fair play will fail.” Of

course, some might find such a talk a little rich, given Dortmund’s own

checkered history, especially as they were given a €2 million loan at the

height of their problems by Bayern Munich (of all people).

"Bender - Sven you're young"

As to the future, Dortmund are cautiously optimistic. Watzke

sees “additional growth potential” with net profit for 2012/13 likely to be “in

the single digit million range”, assuming exits at the group stage of the

Champions League and the second round of the DFB Cup.

The chairman said that Dortmund were at the fifth stage of a

five-point plan: “The first was the struggle for survival, the second

restructuring, the third was development of a sporting philosophy, the fourth

implementation and the fifth is sustainability.” This is not just a reference

to the club’s financial status, but also the ability to maintain their

performance levels on the pitch. It will indeed be a tough challenge to

establish themselves in Europe, while also figuring prominently in the race for

the Bundesliga

title.

The club has attempted to ensure management stability by

extending the contracts of the “holy trinity” of Watzke, Zorc and Klopp to 2016,

but there are no guarantees in football. If Klopp were to leave, that might be

a hammer blow to Dortmund’s ambitions. No manager is irreplaceable, but whoever

followed the magnetic Klopp would certainly have a tough act to follow.

"Rolls Reus"

In the meantime, we should simply enjoy the fabulous

spectacle at Dortmund, where they have proved that a football club does not

have to throw money at the problem, but can win in the right way. First-class

management, astute scouting and a belief in youth development have delivered

trophies to some of the best fans around, while the team’s dazzling displays

have gained admirers throughout Europe.

That’s some accomplishment, especially as they have combined

their sporting excellence with a remarkable recovery from near collapse to a

solid financial position. Coldplay may not be everyone’s cup of tea, but the

lyrics from their breakthrough single seem strangely apposite; “Look at the

stars/Look how they shine for you/And everything you do/Yeah, they were all

yellow.”

.jpg)

.jpg)