It’s fair to say that last season was not particularly

enjoyable for Genoa. They only just managed to avoid relegation, while their

defence was the worst in Serie

A, conceding a horrific 69 goals. Matters came to a head when a

group of their fans staged a protest during the 4-1 home defeat to Siena,

throwing flares and demanding that the players gave them their shirts, leading

to a 45 minute suspension of the match.

That evening Genoa’s volatile president Enrico Preziosi

sacked the coach Alberto Malesani, replacing him with Luigi De Canio, who will

be hoping to get the fans back on board this season with his own brand of

attacking football. Of course, he may not be helped by the huge amount of

player movements (in and out), which has become the normal state of affairs at

the Luigi Ferraris.

In particular, Genoa sold their leading scorer, the

Argentine striker Rodrigo Palacio, to Inter, while they also let Alberto

Gilardino move to Bologna on loan. In their place, they brought in last

season’s Serie B

top scorer, the unfortunately named Ciro Immobile, from Pescara and former

striker Marco Borriello, who has strutted his stuff with limited success for

numerous clubs, but in fairness did net an impressive 19 goals for Genoa in the

2007/08 season.

"Borriello - return of the prodigal son"

More positively, this is Genoa’s sixth consecutive season in

Italy’s top flight, which represents a major improvement after all the time

spent in the lower leagues in the preceding years and is virtually

unprecedented post-war. Although Genoa have a glorious past, winning the

Italian title no fewer than nine times, the last of these victories came in

1924, so it’s somewhat ancient history.

Preziosi took over the club in 2003, just after the club had

been relegated to Serie

C1, though Genoa were saved by the Italian Football Federation’s

controversial decision to expand Serie

B to 24 teams after the infamous Caso

Catania. Two years later Genoa became Serie

B champions, but were demoted to C1

after they were found guilty of match fixing the vital final game against

Venezia. Despite being given a three-point penalty, Genoa finished as

runners-up the next season, securing an immediate return to Serie B after

winning a play-off against Monza.

The following season Genoa achieved a second successive

promotion, reaching Serie

A in 2007, a testament to Preziosi’s support during this turbulent

period. Until the last troubled season, Genoa have been comfortable in the top

tier, finishing in the top half of the table four years in a row, including a

memorable fifth place in 2008/09, when they narrowly missed out on Champions

League qualification, largely thanks to the efforts of two players brought in

from the Spanish league, the prolific Diego Milito and a rejuvenated Thiago

Motta.

"Preziosi - buy or sell?"

However, Preziosi is a man who divides opinion. The former

Como owner is a successful businessman, making his money from one of the

world’s largest toymakers, and it is clear that he has calmed the waters at

Genoa while providing substantial financial support. Indeed, he acquired the

club from the liquidator of Genoa’s parent company after they had suffered from

having three different owners in the previous six years.

On the other hand, he has been involved in countless clashes

with the authorities. Only last week he was banned from attending football

stadiums for six months as a much-delayed punishment for the 2005 match fixing

case.

Preziosi’s Genoa have also been heavily involved in the “bilanciopoli” case,

a false accounting scandal whereby football clubs inflated the value of their

players in order to improve the balance sheet. In particular, the fiscal

authorities targeted Genoa’s 2004 and 2005 accounts, resulting in fines and

bans, though a few years later the club was half-cleared with the tribunal

ruling that there were no false invoices, but that the accounts were

manipulated in some way.

Hence, the raised eyebrows at Genoa’s frenetic transfer

activity. Since 2008 the club’s net spend in the transfer market is only €8

million, but this disguises a key point, namely the enormous turnover of

players coming in and out. So that net €8 million actually represents a barely

credible €272 million of purchases and €264 million of sales in just five

seasons.

Not for nothing is Preziosi known as the “king of the

transfer market”, though he has pointed out that it does not matter how the

club performs on paper and he should be judged by displays on the pitch.

Clearly, such a massive movement of players each season makes it difficult for

the squad to gel, but this business model is imperative for the club’s

fortunes. In short every player is for sale at the right price with most of the

funds reinvested in cheaper alternatives that are (hopefully) then sold for a

fat profit at a later date.

The club has been trading players like stocks or commodities

for the last few years, but there has been a modification in their approach

recently. After the promotion to Serie

A, Preziosi splashed the cash with a net outlay of €57 million in

three seasons, but the last two seasons Genoa have looked to sell more players,

the latest big money departures being Miguel Veloso to Dynamo Kiev and Mattia

Destro to Roma (a paid loan with option to buy). In fact, in that period only

Udinese, the acknowledged masters of player trading in Italy, have higher net

sales proceeds than Genoa’s €49 million.

The harsh reality is that Genoa simply do not have the

financial resources to hang on to their star players, as can be seen by looking

at their profit and loss account. At first glance, it does not seem too bad

with the club just about breaking even and actually making a pre-tax profit of

€1.8 million in 2011 (though they made a hefty loss of €17 million the previous

year), but this is heavily impacted by player trading through player sales and

co-ownership deals.

Excluding player trading, the club makes massive operating

losses: a frightening €156 million in the last three years, including €67

million in 2011 alone. This includes non-cash expenses such as player

amortisation and depreciation, but even EBITDA (Earnings before Interest,

Taxation, Depreciation and Amortisation) is strongly negative, e.g. €23 million

in 2011.

It should be noted that Genoa changed their accounting close

in 2008 from 30 June to 31 December, so the accounting year now straddles two

seasons, e.g. 2011 includes the second half of the 2010/11 season and the first

half of 2011/12. This is a somewhat bizarre feature of a few Italian clubs,

though is sometimes done to be in line with the parent company’s reporting

timetable.

Regardless of the accounting close, the impact of player

trading on Genoa’s accounts is undeniable. In fact, the club would have reported

a loss of €73 million in 2011 without the money made from player sales (€58.8

million) and co-ownership deals (€13.8 million).

Profit from player sales is simple enough, being the

difference between sales proceeds and the remaining value of the players sold

in the accounts, though the slight twist is that the €58.8 million comprised

€62.2 million of plusvalenze

(profitable sales) less €3.8 million of minusvalenze (loss-making sales including settlement

of player contracts, such as Anthony Vandenborre €1.5 million).

Co-ownership deals are a little more complex, though such

arrangements are very common in Italy, whereby two (or more) clubs share the

ownership of a player’s rights. This is regarded as a good way to lower costs

and reduce risk when purchasing a player, though the practice is banned in

England and France. Astonishingly, Genoa had 24 co-ownership deals on their

books in 2011.

"Granqvist - handy Andy"

When such a joint ownership agreement is terminated, any

payment higher than the amount on the balance sheet is treated as a gain (“un provento”),

while any lower payment is shown as an expense (“un

onere”). In Genoa’s 2011 accounts, this produced a net gain of €13.8

million, made up of a €17m gain, mainly Andrea Ranocchia (Inter) €6 million,

Bosko Jankovic (Palermo) €3.5 million, Giuseppe Sculli (Lazio) €3 million,

Raffaele Palladino (Juventus) €2 million and Kevin-Prince Boateng (Milan) €1.75

million, less €3.2 million expenses.

The sums involved in player trading were not quite as high

in earlier years, but they were still significant with profit on player sales

of €38 million in both 2009 and 2010 plus gains from co-ownership deals of €3.2

million in 2009 and €7.1 million in 2010.

Genoa also received €3.7 million of revenue from player

loans in 2011, largely from Robert Acquafresca going to Cagliari (€1 million)

and Mattia Destro to Siena (€750,000). This was one of the highest loan

revenues in Serie A,

which should not be too surprising, given the large number of players Genoa

have out on loan to other clubs (26 for the 2012/13 season). On the other hand,

they paid out €2.5 million on inward player loans (mainly Antonio Floro Flores

from Udinese €1.5 million) and €2.1 million on player development costs.

Despite these vast sums from player trading, Genoa have

struggled to balance the books, reporting only one profit in the last 41 years

(€1.5 million in 2008). In particular, they spent big when they were in Serie C1 and Serie B in a

(successful) attempt to get promoted, leading to large losses in both 2005 (€14

million) and 2006 (€11.5 million). Since their return to Serie A, they have

basically managed to keep their losses under control via their expert use of

player trading with the exception of 2010’s sizeable deficit.

That 2010 loss of €17 million was used in the Serie A profit

league presented by La

Gazzetta dello Sport earlier this year for the 2010/11 season and

was only surpassed by the “big four” clubs who reported enormous losses, as has

been the case in Italy for many years: Juventus €95 million, Inter €87 million,

Milan €70 million and Roma €31 million. In fairness to the rossoblu, only 8

clubs in Serie A

managed to make money that season, and they did substantially improve their

position to a tiny loss in 2011.

We also need to recognise that Genoa have done well with

their finances if we take into consideration their relatively low recurring

revenue streams (match day, television and commercial income). Their annual

revenue of €48 million is only the 11th highest in Italy and a long way behind

the leading clubs. The two Milanese clubs generate more than four times as much

(Milan €220 million, Inter €211 million), while Juventus (€154 million), Roma

(€144 million) earn three times as much, while Napoli (€115 million) have to be

content with twice as much.

Even Lazio, Fiorentina and Palermo all receive at least €20

million more a season than Genoa. Interestingly, the club that is closest to

Genoa in revenue terms is Udinese, who have also focused on player trading as a

way to generate funds.

In this way, Genoa’s plusvalenze

represent a hefty chunk of the club’s revenue. In 2010 the €38.9 million was

equivalent to 68% of the club’s revenue, a proportion bettered only by Parma

81% and Udinese 77%. In 2011, Genoa’s plusvalenze

was worth an amazing 110% of their revenue.

The above analysis also highlights the differences between

how revenue is reported in Italy and other European countries. The European

definition used by Deloitte in their annual money league amounts to €48.1

million for Genoa in 2011, while the club itself announced record revenues of

€118.8 million. The €70.7 million difference is due to: (a) player loans €3.7

million; (b) gate receipts given to visiting clubs €0.1 million; (c) increase

in asset values €4.7 million; (d) profit from player sales (plusvalenze only)

€62.2 million.

Taking a closer look at the plusvalenze

Genoa has reported over the last few years reveals that much of this has come

from sales to Inter and Milan. In 2011, of the total €62 million, nearly €32.7

million was from Milan (on sales proceeds of €57.9 million), while a further

€12.8 million was from Inter (for Juraj Kucka on sales proceeds of €16

million). The sales to Milan involved no fewer than eight players contributing

profits as follows: (deep breath) Stephen El Shaarawy €19.8 million, Matteo

Chinellato €3.5 million, Alberto Paloschi €2.3 million, Gianmarco Zigoni €1.8

million, Tuncara Pele €1.7 million, Nnamdi Oduamadi €1.6 million, Rodney

Strasser €1.1 million and Marco Amelia €0.9 million.

In 2010 Genoa also made €16.8 million from Milan (Sokratis

Papastathoupolus €12 million and Kevin-Prince Boateng €4.8 million) and €11.3

million from Inter (Andrea Ranocchia), while 2009 featured €28.6 million from

Inter (Diego Milito €18.5 million and Thiago Motta €10.1 million).

Genoa’s relationship with the rossoneri

in particular has been mutually beneficial with Milan’s profit and loss account

similarly being boosted by profit on sales of players to Genoa to the tune of

€24.4 million in 2010 and €17 million in 2011. In particular, Milan sold a 50%

share in several youngsters (Oduamadi, Beretta, Zigoni and Strasser) to Genoa

in 2010, realising a handy profit in their books, only to buy all of them back

(with the exception of Beretta) the following season.

Preziosi has been quoted as saying, “Our club must have good

relations with the big clubs”, but this very close relationship does seem a bit

strange, exemplified by Genoa buying Kevin-Prince Boateng from Portsmouth on 18

August 2010 and loaning him to Milan on the very same day. The contract was

later switched to co-ownership before Milan purchased Boateng’s full economic

rights in May 2011.

Those of a cynical nature might wonder about all the money

earned from plusvalenze

on both sides, especially after the many investigations in the past into

manipulated accounts, but it may just be the case that there are few clubs that

Genoa can sell to in Italy. As sporting director Stefano Capozucca said, “There

are only two clubs, three at the most, who can afford to spend (these days).”

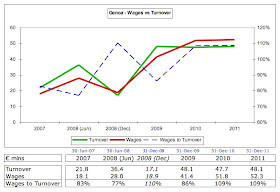

The importance of player trading to Genoa’s business can be

seen once again in the above graph with profit on player sales and gains from

co-ownership deals providing the only “revenue” growth in the last three years.

The last time that ongoing revenue grew meaningfully was in 2008 after the

promotion to Serie A,

when it virtually doubled from €22 million to €38 million, but since 2009 it

has been effectively flat at around the €50 million level.

Of the traditional revenue streams, television is by far the

most important with €32 million in 2011, compared to €10.4 million of

commercial income and just €5.7 million of match day revenue.

Genoa’s TV revenue of €32 million is far lower than the

leading Italian clubs with Juventus, Inter and Milan all earning around €80

million, while other Italian clubs also receive a fair but more, e.g. Napoli

and Roma get around €60 million; Lazio about €50 million; and Fiorentina,

Palermo and Udinese around €40 million.

It is anticipated that the new collective agreement that

started in the 2010/11 season, but was only half reflected in Genoa’s 2011

accounts, should produce a small increase of €3-4 million, as the allocation

benefits the mid-tier clubs to a certain extent. Under the new methodology, 40%

is divided equally among the Serie

A clubs; 30% is based on past results (5% last season, 15% last 5

years, 10% from 1946 to the sixth season before last); and 30% is based on the

population of the club’s city (5%) and the number of fans (25%).

The improvement also reflects the fact that the total money

negotiated in the new deal is approximately 20% higher than before at almost €1

billion a year. This cemented Italy’s position as the second highest TV rights

deal in Europe, only behind the Premier League, which continues to sign ever

more lucrative contracts, but significantly ahead of the other major leagues,

despite the Bundesliga

increasing its rights by over 50% for the next four-year deal.

That’s particularly impressive, given how little is received

for foreign rights (at least compared to the Premier League), though it was

recently announced that the incumbent rights holder, MP & Silva, will pay

an additional 30% for these rights for the three years starting from the

2012/13 season (up from €90 million a year to €115-120 million). Domestic

rights are now worth €829 million a season, with €561 million from Sky Italia

and €268 million from Mediaset.

Of course, Genoa could really grow their television revenue

if they were to somehow qualify for the Champions League. This might seem a bit

of a pipe dream, especially now that Italy have lost a place to Germany after

their deteriorating UEFA co-efficients, but as recently as 2009 they finished

fifth, only just missing out on a seat at Europe’s top table because Fiorentina

had a better head-to-head record.

They did manage to qualify for the 2009/10 Europa League,

the first time they had reached Europe in 17 years, and earned €1.6 million

from the central TV distribution in the process, but this is peanuts compared

to the riches available from Europe’s flagship tournament, e.g. in 2011/12 the

Italian representatives earned an average of €33 million (Milan €39.9 million,

Inter €31.6 million and Napoli €27.7 million). In addition, they would benefit

from higher gate receipts (a €2 million increase in 2009) and improved

sponsorship terms.

Like all Italian clubs, Genoa’s match day income is on the

low side at around €6 million. In 2010/11 only six clubs in Serie A took in more

than €10 million a season: Inter €33 million, Milan €30 million, Napoli €22

million, Roma €18 million and Juventus €12 million. That’s considerably more

than Genoa, but pales into insignificance compared to the top European clubs

like Real Madrid €124 million and Manchester United €120 million.

Genoa’s average attendance of 21,995 in 2011/12 was the

eighth highest in Italy, utilising around 60% of the stadium capacity, just

behind Fiorentina 23,402 and ahead of Palermo 20,945. Crowds rose in line with

their ascent through the leagues, but have dipped alarmingly in the past two

seasons since the peak of 26,802 in 2009/10. Part of this decline can be

attributed to the poor economic environment, but it is likely that some is also

due to the supporters’ unhappiness with Genoa continually selling their best

players.

In the past few years there have been many initiatives to

improve the stadium. The Stadio Luigi Ferraris is shared with Sampdoria and is

located in a heavily built-up area, leading to initial thoughts that a new

stadium would have to be constructed elsewhere with a site at the marina di

Sestri Ponente being tentatively identified as one possibility. However, this

was rejected by the council, so the idea of renovating the current stadium once

again took shape with plans presented by the Fondazione Genoa 1893 in late

2009.

The aim was to transform the old ground into a modern

stadium that could generate revenue seven days out of seven, emphasising the

commercial possibilities and installing premium seats including 28 “skyboxes”.

The capacity would be reduced from 36,600 to 33,000, but the revenue would be

considerably higher. The project would cost less than €50 million.

However, the plans were not supported by the Italian

football federation, so were once again put on the back burner. Last summer,

another initiative was raised, whereby Genoa and Sampdoria would take over the

management of the stadium from the council, leaving a specialist company to

handle the commercial aspects. However, despite Preziosi’s admiration for

Juventus’ new stadium, yet again these plans fizzled out, though last month the

stadium management was taken over by a new consortium of four Italian companies,

so perhaps all is not yet lost.

There is also room for growth in the club’s commercial

revenue, which actually slightly decreased in 2011 to €10.4 million from €11.5

million. This is understandably a lot lower than the big boys (Milan €80

million, Inter and Juventus both €54 million), but is also less than clubs like

Palermo €18 million and (more painfully) local rivals Sampdoria €15 million.

Genoa earned €1.8 million from their shirt sponsorship deal

with Iziplay, a betting company, in 2011, which was around double the €0.9

million they received the previous year. This is a lot less than many other

Italian clubs: Milan – Emirates €12 million, Inter – Pirelli €12 million,

Juventus – BetClic €8 million, Roma – Wind €7 million, Napoli – Acqua Lete €5.5

million and Fiorentina – Mazda €4 million.

Those clubs also receive higher sums from their kit

suppliers than the €1.1 million Genoa booked in 2011 from Asics (Inter – Nike

€18 million, Milan – Adidas €17 million, Juventus – Nike €12 million, Roma – Kappa

€5 million and Napoli – Macron €4.7 million).

Genoa will be hoping that their six-year arrangement with

Infront will boost their commercial income. They have already brokered the

higher sponsorship deal with Iziplay and this summer signed a new four-year

deal with Lotto Sports running until June 2016 to replace Asics as kit

supplier. Infront’s president, Marco Bogarelli, said, “Our principal objective

will be to contribute towards a better balance in the revenue, which is

currently over-reliant on television.”

Something needs to be done to improve revenue, as Genoa are

facing a real battle to contain their staff costs. Although their wages were

more or less unchanged from the previous year at €52 million in 2011, they have

risen 87% (€24 million) since they returned to Serie

A in 2007/08, while revenue has only grown by 32% (€12 million) in

the same period. Genoa’s annual report explained that the significant increase

in costs in 2010 was due to “an important investment in players, both

youngsters with potential and more experienced internationals.”

Using the standard definition of revenue, i.e. excluding

profit from player trading, the wages to turnover ratio has been a worrying

109% for the last two years, up from 86% in 2009. As sporting director

Capozucca acknowledged, “Nobody is denying that errors have been made at the

management level. We have spent more than we should.”

The wages to turnover ratio is the worst in Serie A, even higher

than Milan, Inter and Juventus, who all hover around the 90% mark, and way

above UEFA’s recommended upper limit of 70%. That said, Genoa’s wage bill of

€52 million is considerably lower than the leading clubs: Milan (€193 million)

and Inter (€190 million) pay almost four times as much as Genoa, while Juventus

(€140 million) are nearly three times as much and Roma (€107 million) are more

than €50 million higher. On the other hand, Genoa’s wage bill is about the same

as Napoli and nearly twice as much as Udinese, who both qualified for the

Champions League that season, so they have arguably under-performed.

As per the 2011 accounts, the €52.3 million wage bill

included the following: player salaries €38.8 million, coaches and technical

staff salaries €4.9 million (probably including sacked coaches on gardening

leave), bonus payments €2 million, other staffs €3.8 million and social

security €2.9 million.

"Kucka - Slovakian steel"

According to the annual salary survey published by La Gazzetta dello Sport,

the wage bill for Genoa’s first team squad has been cut from €36 million last

season to €29 million for the 2012/13 season, so it looks like Preziosi has

finally decided enough is enough (though the newspaper figures come with a

health warning regarding accuracy). The same report stated that only four

players at Genoa earn more than €1 million a season: Borriello €1.4 million,

Frey €1.3 million, Vargas €1.2 million and Tozser €1 million.

The other element of staff costs impacted by Genoa’s player

trading strategy, especially the very large roster of players, is player

amortisation. This is the way that a club’s accounts reflect transfer

purchases, i.e. by not expensing the full cost immediately, but instead writing

it off over the length of a player’s contract. As an example, defender Luca

Antonelli was signed for €7.35 million on a 4½-year contract, but his transfer was

only reflected in the profit and loss account via amortisation, booked evenly

over the life of his contract, i.e. €1.6 million a year (€7.35 million divided

by 4½ years).

Genoa’s player amortisation has surged from just €4 million

in 2007 to €41 million in 2011, a figure only surpassed in Italy by Milan €52

million, Inter €50 million and Juventus €47 million. Perhaps a better

comparative is Udinese, who have much the same revenue as Genoa and also focus

on player trading, but their player amortisation is only €17 million.

Admittedly, this is not a cash expense, but it does reflect the cash outlay on

player purchases.

This has been reflected in ever-increasing liabilities,

which have shot up from €35 million in 2007 to €285 million in 2011, including

a 38% increase in the last 12 months alone. Furthermore, since 2007 financial

debt has surged from €7 million to €109 million, comprising €22 million of bank

debt with Banca Unicredit and Banca Cariga, €59 million owed to factoring

companies (Banca Cariga and l’Istituto per il Credito Sportivo) based on future

income plus €28 million of shareholder loans.

Of course, Genoa are not unique in facing growing debts in

Italy, as the last football federation report noted, with the total liabilities

in Serie A

growing 40% since the 2007/08 season, notably bank debt, commercial debt and

outstanding transfer fees.

As might be expected, the latter factor is significant for

Genoa, who owed €98 million to other football clubs for transfer fees in 2011,

though this is more than offset by the €119 million owed to Genoa by other

clubs.

The balance sheet has net assets of €1 million, one of the

weakest in Serie A,

with net current liabilities rising from €119 million in 2010 to €153 million

in 2011. Once again, it is dominated by the effects of player trading with the

assets including an incredible €123 million for player registrations. To put

that into context, it is not much less than Inter €143 million and Milan €136

million, but is much more than Juventus €71 million and Roma €37 million. The

other experts of the “buy low, sell high” game, Udinese, are also much lower at

€48 million.

Genoa’s assets also include €31 million for co-ownership,

which is equivalent to half the value of players transferred in co-ownership

deals. This includes three players sold to Milan (Stephen El Shaarawy €10

million, Matteo Chinellato €1.75 million and Tuncara Pele €0.95 million), Juraj

Kucka to Inter (€8 million), Federico Rodriguez to Bologna (€3 million) and

Francesco Acerbi to Chievo (€2 million).

Similarly, the liabilities include €25 million for

co-ownership: four players bought from Milan (Alexander Merkel €5 million,

Giacomo Beretta €4 million, Nicola Pasini €1.65 million and Mario Sampirisi €1

million), Emiliano Viviano from Inter €5 million and Andrea Esposito from Lecce

€2.8 million.

Nevertheless, Preziosi has needed to provide a great deal of

financial support to the club with the amount of money he has put in over the

years approaching €70 million. He summed up his approach last year, “With me

Genoa will always be in Serie

A and if that is not enough for some fans, they should look for a

Qatari sheikh. I will try to strengthen the squad, but I must also look at

balancing the books, otherwise there is no future.”

"Antonelli - his name is Luca"

The president has hinted on many occasions that he might

sell the club with rumours of a few possible buyers circulating in recent

months, including the inevitable representatives from the Middle East and (more

plausibly) the industrialist Vittorio Malacalza, with a potential takeover

price of €40 million.

However, Preziosi has seemed reinvigorated this season. It

had looked like he would take a step back when he hired Pietro Lo Monaco from

Catania in the summer as general manager to handle all aspects of the club’s

activities – with the important exception of transfers. However, after some

disagreements over, you’ve guessed it, the transfer market, Lo Monaco exited

stage left after just two months, leaving Preziosi as once again indisputably

the main man.

A few months ago, Preziosi suggested that there would be

less buying and selling of players in the future, “The fans will be happy, as

there will no longer be such a whirlwind of trading and less (player)

turnover.” Of course, that would require two things: (a) a leopard (that would

be Preziosi) to change its spots; (b) a serious improvement in the club’s

operating losses, meaning an increase in revenue or (more likely) a reduction

in costs. Whether these are possible, only time will tell.

European qualification would obviously help, though only the

Champions League would make a real difference to the club’s finances, but that

now requires clubs to meet the criteria of UEFA’s new Financial Fair Play (FFP)

regulations, which will ultimately exclude from European competitions clubs

that continue to make losses.

However, Genoa look to be in pretty good shape, assuming

that they continue to make good profits from player trading, as wealthy owners

will be allowed to absorb aggregate losses (“acceptable deviations”) of €45

million, initially over two years and then over a three-year monitoring period,

as long as they are willing to cover the deficit by making equity

contributions.

To be more sustainable, they would need to deliver on their

plans to grow commercial revenue, increase gate receipts from a refurbished (or

new) stadium and lower their wage bill, which is out of proportion for a club

of their size.

"Jankovic - spreads his wings"

The awful dilemma for Genoa is that the only thing that

keeps the club relatively stable financially is their frenetic player trading,

which is also the thing that hurts their chances of progressing on the pitch.

Given their financial weaknesses, it is certainly understandable that they have

chosen to go down this path, but the question is how do they find their way

back to a more “normal” strategy and reduce their reliance on player sales

(mainly to Milan)?

As sporting director Capozucca conceded this month, “We

cannot think of developing a great Genoa team… when we don’t have the economic

resources to do so.” That comment may be harsh, but, after looking at the

club’s finances, it’s also very fair.